The European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR) plays an important role in the Fiqh al-'Aqalliyyat ("Jurisprudence for Minorities") world. It is now based in Dublin, having been founded in London in 1999 by the Federation of Islamic Organizations in Europe. Apart from issuing fatwas (principally those of leading Muslim Brotherhood ideologue, Shaykh Yusuf al-Qaradawi), it aims to supervise the education in Europe of local imams, to bring together Muslim scholars living in Europe, to resolve issues that arise on the continent (and UK) while operating with strict respect for shari'a law (which implies there should be no compromise), and to establish itself as an approved authority wherever Muslims live as minorities. This latter aim would suggest that the ECFR might one day possess an authority that would override that of local and national shari'a councils, and its members would expect to be the first and perhaps only voice to which parliaments and parliamentary bodies would lend an ear in their deliberations on how to treat their Muslim minority communities.

Despite the claim of the ECFR and other bodies involved in guidance for Muslims living outside Islamic jurisdiction to work towards a modus vivendi with Western governments, laws and cultural norms, the members of the ECFR nevertheless tend to approach this challenge in a way that can make the rapprochement problematic. Two matters engage much of their attention, namely secularism and democracy. Al-Qaradawi has spoken and written clearly on these. In one of his books, he separates Christian and Muslim beliefs:

Secularism may be accepted in a Christian society but it can never enjoy a general acceptance in an Islamic society. Christianity is devoid of a shari'ah or a comprehensive system of life to which its adherents should be committed. The New Testament itself divides life into two parts: one for God, or religion, the other for Caesar, or the state: "Render unto Caesar things which belong to Caesar, and render unto God things which belong to God" (Matthew 22:21). As such, a Christian could accept secularism without any qualms of conscience....

The acceptance of a legislation formulated by humans means a preference of the humans' limited knowledge and experiences to the divine guidance: "Say! Do you know better than Allah?" (2:140).... For this reason, the call for secularism among Muslims is atheism and a rejection of Islam. Its acceptance as a basis for rule in place of Shari'ah is downright riddah [apostasy].... This concept is totally different from that of Muslims. We Muslims believe that Allah is the sole Creator and Sustainer of the Worlds. One Who "...takes account of every single thing" (72:28); that He is omnipotent and omniscient; that His mercy and bounties encompasses everyone and suffice for all. In that capacity, Allah revealed His divine guidance to humanity, made certain things permissible and others prohibited, commanded people observe His injunctions and to judge according to them. If they do not do so, then they commit kufr [unbelief], aggression, and transgression." [1]

Al-Qaradawi considers himself to be a moderate, but that is not always obvious from the positions he takes. He originally rejected democracy, but later advanced the proposition that liberal democracy functions in majority Islamic countries as an alternative to dictatorship and tyranny. The problem with this should be obvious. There have never been any effective democracies in the Islamic world. Democracies require a secular approach that involves the separation of church and state even where religion is given an important role to play.

The idea that human beings can replace God as legislators is obnoxious to classical Islamic thought and to modern Islamist convictions. Men and women do not choose how to live: God has been there first. He has sent down his laws through the Qur'an, the utterances of the Prophet, or the deliberations of the law schools. Since shari'a is all-embracing, only the most emboldened reformers dare to limit it to devotional or personal issues, to go so far as to make observance of its rulings a matter for individual choice, or even to relegate the bulk of it to history.

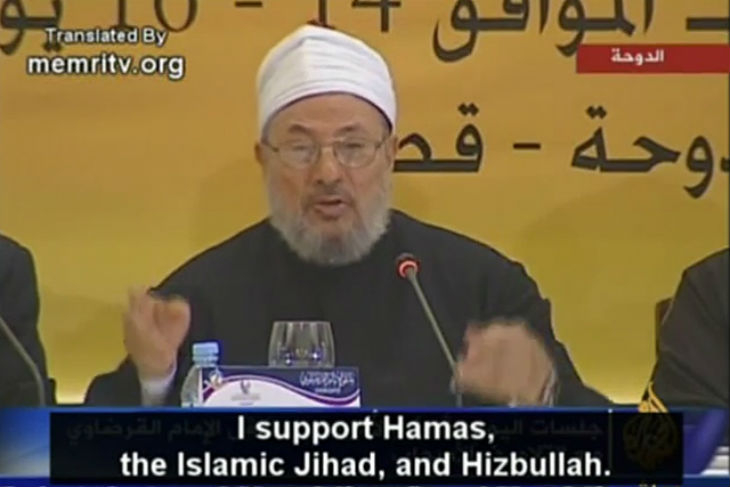

Yusuf al-Qaradawi (Image source: MEMRI video screenshot) |

Several of the ECFR's own pronouncements indicate an unwillingness to compromise with European norms. One fatwa issued by al-Qaradawi tackles the question of challenges to the applicability of shari'a, in answer to which he says, among other things:

The Shari'ah is for all times to come, equally valid under all circumstances. The Muslim insistence on the immutability of the Shari'ah is highly puzzling to many people, but any other view would be inconsistent with its basic concept. Those who advise bringing it into line with current thinking recognize this difficulty. Hence they recommend to Muslims that the legal provisions in the Qur'an and the concept of the Prophet as law-giver and ruler should be "downgraded".

But, as the manifestation of Allah's infinite mercy, knowledge and wisdom, the Shari'ah cannot be amended to conform to changing human values and standards, rather, it is the absolute norm to which all human values and conduct must conform; it is the frame to which they must be referred; it is the scale on which they must be weighed.

The ECFR is not the only body determined to insist on the immutability and absolutism of shari'a law. According to Soeren Kern:

"the Union of French Islamic Organizations (UOIF), a large Muslim umbrella group linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, has issued fatwas that encourage French Muslims to reject all authority (namely, secular) that does not have a basis in Sharia law."

References to several other European Islamic bodies may be found in the remainder of Kern's article.

Dr. Denis MacEoin is the author of Sharia Law or One Law for All as well as many academic books, reports, and hundreds of academic and popular articles about Islam in many dimensions. He is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute.

[1] For a wide discussion of this issue, see Gabriele Marranci (ed.), Muslim Societies and the Challenge of Secularization: An Interdisciplinary Approach, New York, 2010, 2012