The security situation across northern Nigeria is unstable-to-terrible. The Islamists of the Boko Haram group have threatened to eradicate Christianity through a campaign of violence against Christians and churches, and have killed 2,000 people including moderate Muslims in four years.

Further, the next federal elections are planned for just twelve months' time; during the last ballot in 2011 the re-election of Christian presidential candidate, Goodluck Jonathan, resulted in the death of 800 Christians and other minorities and the destruction of up to 300 churches at the hand of rioting Muslim protestors in the twelve northern Sharia states.

Nonetheless, Dr. Bala Takaya, vice-president of Nigeria's Middle Belt Forum, former head of the Department of Political Science at Jos University and alumnus of the London School of Economics, is hopeful. Speaking to the media outside the second Stefanos Foundation conference for the country's northern ethnic minorities -- an initiative of Gatestone Institute held in Abuja recently -- he claimed that the northern minorities are becoming stronger and more united. "We have come of age," he said.

Inside, he had reminded the gathering how for a hundred years the minorities in Muslim-majority northern Nigeria had been oppressed and held back both by the Fulani Islamic elite and, until independence in 1960, by the British colonial masters. But now better education, increasing consciousness and hard-won political experience has resulted in the grass-roots growth of a "Middle Belt" identity separate from the dominant Fulani-Hausa Muslim culture. "The yoke is broken. The shackles are being thrown off. The time is now," he told delegates.

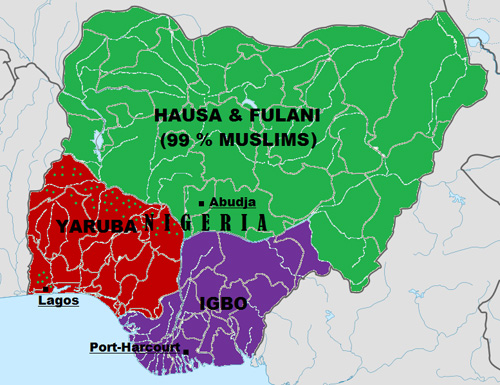

In line with the governance structure imposed by colonial administrators, Nigeria -- at 170 million, Africa's most populated country -- is frequently recognized as two separate regions with a common border and a joint federal government: and the larger but more dispersed mainly-Muslim North, and the geographically smaller but more intensely populated Christian-majority South.

Ethnically the North is dominated by Hausa tribal language and culture, while the South is identified with the main Yoruba and Igbo tribes.

A religious-ethnic map of Nigeria. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) |

But these political and ethnic monoliths betray an on-the-ground diversity that is politically inconvenient and therefore regularly ignored. It has been calculated that there are over 800 different tribal and linguistic groups across the country. A recent book by the journalist Rima Shawulu Kwewum, for instance, calculates that Bauchi State -- the seventh largest of Nigeria's 37 states – has ninety ethnic groups and nationalities, while Adamawa and Taraba States have over a hundred. For many Nigerians the local tribe is a prime source of identity.

Nowhere is tribal attachment stronger than in the polyglot southern areas of Northern Nigeria – the "Middle Belt" of the country which was first tentatively claimed as a separate collective entity as long ago as the 1930s. Comprising mainly Christian and Traditional African (British administrators called them "Pagan") tribes, 'Middle Belters' -- who are found indigenous in even the most northerly Sharia states of Borno, Yobe and Kebbi -- have increasingly asserted their ethnic distinctiveness, and rejected northern Fulani/Hausa hegemony with its second class dhimmi status for non-Muslims.

"(We have) historically found solidarity and expression in feelings of alienation and deprivation based on [our] crude and systematic subordination, oppression, suppression and exploitation," explained a Middle Belt Forum leaflet some years ago. MBF counters the oppression today by "promoting freedom..., respect for human rights, human dignity and the sanctity of human lives".

But ethnic diversity can be a weakness: tribes frequently have a history of local disagreement and even fighting among them. Unity may be strength but cooperation is not necessarily easy.

This is why, according to many delegates, the Gatestone-Stefanos conferences have been important, unique and timely. The events are the first grass-roots initiative for local people rather than state politicians, although some key public figures have attended too. The aim is to find common interest and facilitate local collaboration between minority groups in fifteen of the nineteen northern states. The emphasis is on training: appointing local coordinators, drawing up action plans, planning networking opportunities and setting time-lines.

Despite the tension, the conferences have been calm and focused. During a priority-setting session, "equal opportunity for all tribes and groups," "job creation," "better education," and "recognition of excellence" were rated significantly higher than "defeat of Boko Haram," perhaps because that is seen primarily as the job of the military.

Although the events were about asserting minorities' human rights in the Muslim north, the mood was conciliatory; the organizers anticipate that some marginalized Muslim tribes will join the initiative too in due course. National unity and "One Nigeria" were, informally, the conference strapline; peace-making and nation-building at the local level were the task in hand.

"Middle Belt is in the middle of the country," said Dr. Takaya. "We are the glue that holds north and south Nigeria together."