After weeks of speculation about "Supreme Guide" Ali Khamenei's strategy for dealing with the new Trump administration in Washington, it seems that he has opted for a cocktail of tantalizing pledges and boastful threats. Tehran circles sum the posture up with a simple formula advanced by Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi: We don't want war but are ready for it!

The signal that the Supreme Guide has decided to authorize new talks about his nuclear project but is also preparing for a putative war with the US or Israel came with a poem he put in circulation last week.

Khamenei has been writing or, as his unkind critics suggest, committing poetry since he was in his teens in the 1950s. But he has always been reluctant to offer his oeuvre to the public, refusing to publish a diwan as even the greenest saplings in the garden do.

Thus, those who follow his poetic career know that he publishes a poem only when a major challenge faces him or the regime he inherited from another poet, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

The latest poem is a sonnet (ghazal in Persian and Arabic) of 14 rhyming hemistiches or seven lines (be it in Persian and Arabic) and is supposed to depict the poet's inner struggle with rising fears and persistent doubts.

The message it wishes to pass is one of steadfastness regardless of the Islamic Republic's recent setbacks in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and parts of Yemen held by Houthis.

In a year or so, Khamenei has tried to repackage those setbacks as great victories for his now defunct "Axis of Resistance." His assumption was that if the worst came to the worst, he would play his joker: signaling readiness to revive the defunct Obama "nuclear deal" with a shaky Biden administration keen on securing any deal with Tehran to justify Kumbala's "greatest diplomatic achievement."

The latest poem, however, seems to have been composed after Joe Biden had packed his luggage to leave the White House.

The poet foresees "toil and trouble" on a battlefield and is gripped with fear and trembling. The aim of the poet is to stiffen his backbone with a reminder that he holds "the staff of Moses," which swallowed the snakes and adders pitted against it by the Pharaoh's sorcerers.

The intention is to produce a work of bravura known in Arabic and Persian as rajaz, the ballad that ancient warriors composed and read aloud on the eve of a decisive battle to enthuse their troops and frighten their foes.

Thus, Khamenei demands that his followers be "like a solid rock" leaning only on "a mountain," presumably meaning himself. He insists that he and his followers would not flee from a "call-out" or challenge (da'a in Arabic and Persian).

Classical Arabic and Persian literature offer numerous examples of rajaz that rise to the highest levels of poetic creation. In Arabic, there are such masters as Muhalil Ibn Rahilah, Labid, and a more rough diamond like Antar Ibn Shaddad, not to mention the master of all, Imru' al-Qays, who won the sobriquet of the "King of the Wayward" (al-Malik al-Dhalil) for having kicked Dhul-Khalasah, a mixture of idol and oracle in pre-Islamic Arabia.

In Persian literature, you find the greatest masters of the genre in Onsori, Assadi-Toussi, Asjodi, and Amir-Moezzi.

As a student of poetry, the ayatollah is surely familiar with that rich tradition in both Persian and Arabic.

And yet, surprisingly, he seems to ignore the basic features of the genre, the rules of the game, so to speak.

Arabic and Persian poetry come in nine basic forms, from ghazal to ruba'ee to qasidah or ode, each of which is regarded as suitable for passing a message. If you wish to pass on a bit of wisdom in a short, almost haiku-like form, you go for a ruba'ee. If you wish to narrate a story or preach a doctrine, your best bet is a mathnavi in one of the 13 meters available.

The ghazal is almost always used to convey a romantic view of existence, from reflecting the beauty of a garden to capturing the joy of an evening of merrymaking with friends to wooing a reluctant debutante or even a sin-seasoned Jezebel.

In other words, the ghazal isn't a suitable form for rajaz, which always marches in as a qasidah. But then, a poem that falls short of 13 lines or 26 hemistiches, as the ayatollah's does, cannot be regarded as a qasidah.

Then there is the question of the meter. The meter chosen by the ayatollah suits a ghazal of introspection, romantic fantasy, and music-and-moonlight wooing of a hard-to-get beauty. Rajaz needs a meter that beats the biggest drums and blows into the loudest trumpets.

Ghazal does the work of chamber music, while qasidah is the poetic form of a symphony.

The rajaz begins with narrating the grievances, sufferings, and thirst for vengeance in the name of justice. It hides whatever weakness, doubt, and fears the poet might be harboring, whereas the ayatollah's ghazal depicts a man struck by self-doubt and unspecified fears lurking in the background, as in a haunted house.

Ignoring the "necessity of the unnecessary" rule of rhyming (lozum ma la yazem in Arabic), the ayatollah uses the word magoriz ("don't escape" in Persian) to seal every line.

This is an unfortunate choice in a poem supposedly designed to inspire the stand-and-fight spirit, while the poet casts himself as the heir to "the heroes of Khyber and Badr battles of early Islam."

Needless to say, the ayatollah's poem is devoid of the reiterative metaphors that deepen each other's message, as one nip of the sword widens the wound inflicted by a previous nip. The technique, used masterfully by Onsori, for example, turns the qasidah into something akin to painting by words.

I don't know what mark classical experts on Persian poetry such as Shams Qais Razi or Nizami Arudhi would have given the ayatollah for his rajaz, but those dealing with his Islamic Republic might find some intriguing clues to his hidden thoughts. As for Iranians, they may pray that the man who rules them has more respect for the rules of governance than he shows for the conventions of rajaz.

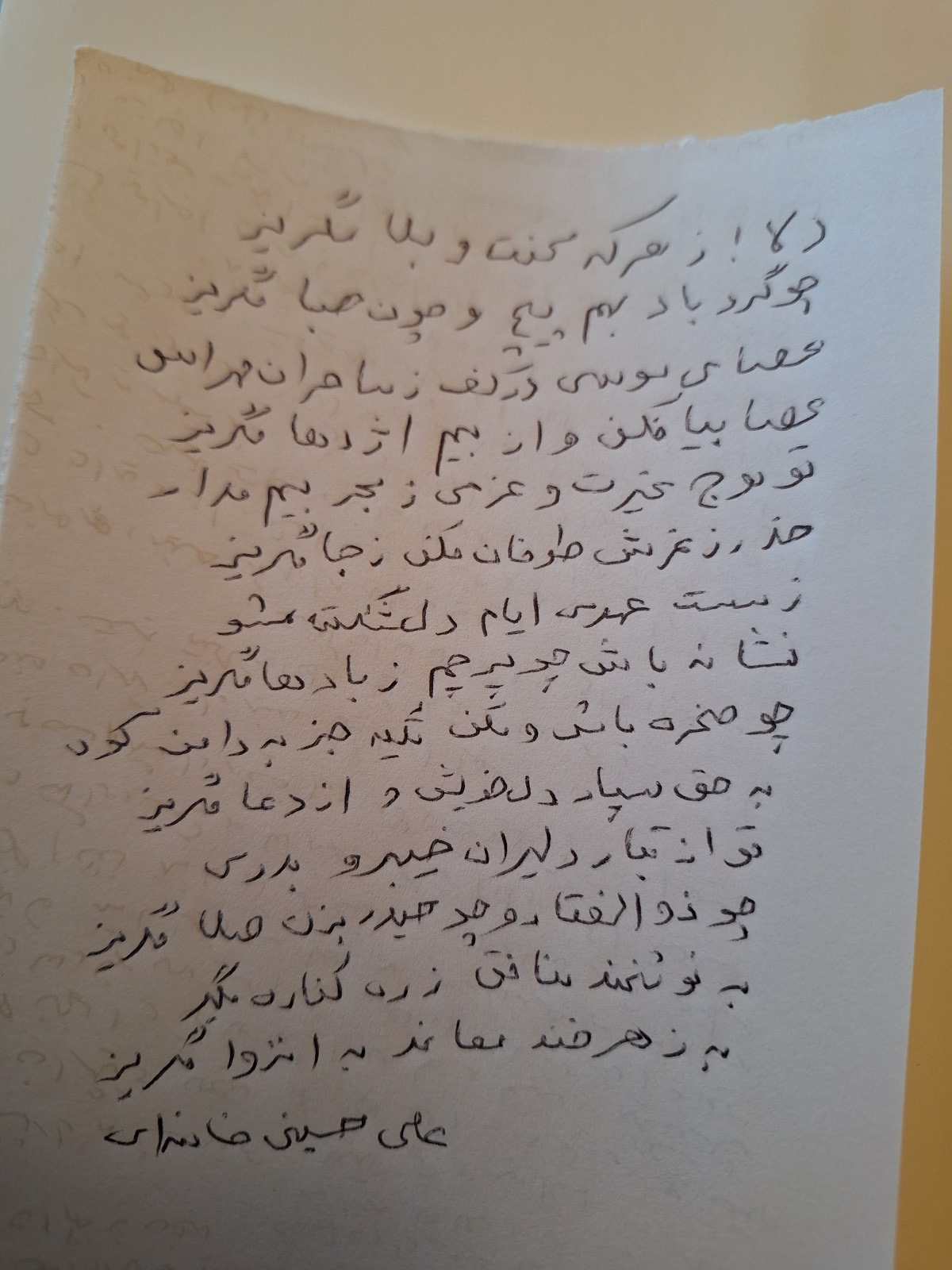

Here is the ayatollah's latest masterpiece:

Dear Heart! From the battle of toil and trouble do not escape

Turn onto yourself like a whirlwind and like the morning breeze don't escapeThe staff of Moses is in your hand, throw it in

fear not the snakes of sorcerers do not escapeYou are the wave of courage and determination, don't fear the sea

ignore the roaring of the storm, from your abode do not escapeDon't be broken-hearted because of the infidelity of these times

Be a symbol like a banner, from the winds do not escape

Be a solid rock and lean only on the mountains

Give your heart to the truth and from call-outs( reckonings) don't escape

You are a descendant of the heroes of Khyber and Badr

Be like Haidar with his double-edged sword, from challenges do not escape

Do not abandon the path with a sweet smile of hypocrites

With the poisonous smirk of a foe into hiding do not escape!

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987.

Gatestone Institute would like to thank the author for his kind permission to reprint this article in slightly different form from Asharq Al-Awsat. He graciously serves as Chairman of Gatestone Europe.