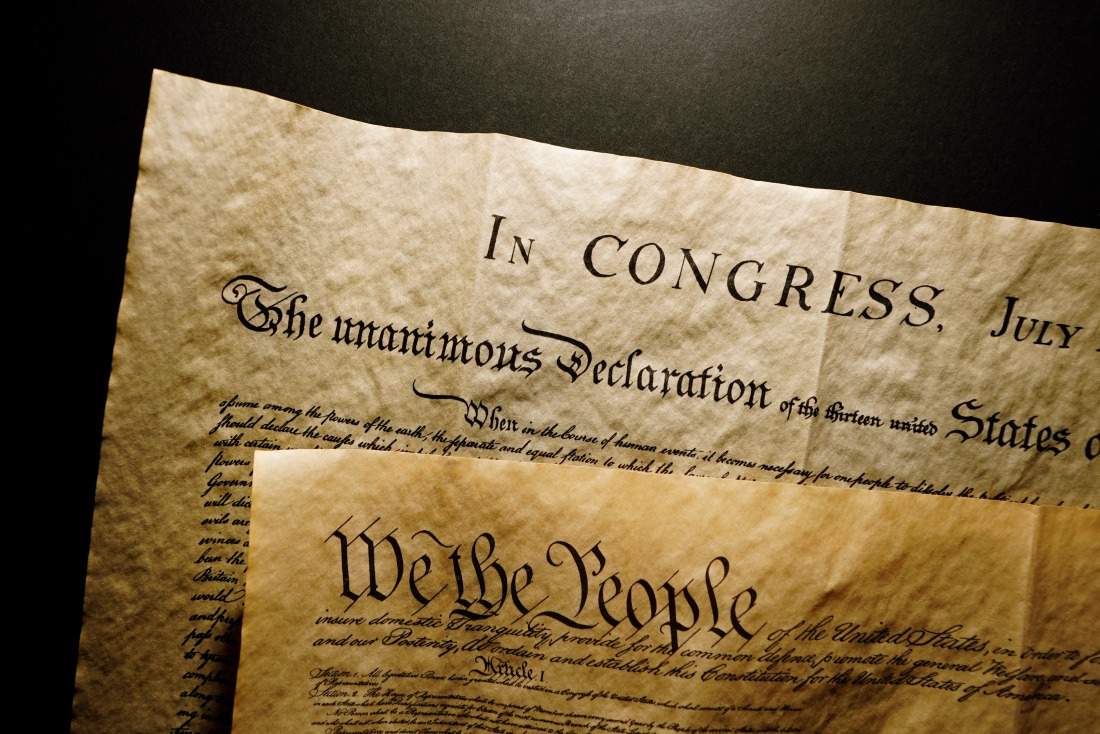

The American system of government is a federation of sovereign states that retain inherent powers not specifically delegated to the national government. It is a republic that separates discrete powers among coequal and competing branches of government — namely the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial. It is a representative democracy that empowers the people to vote into office those who presumably will best serve their interests. Most importantly, it is a constitutional system that severely limits government's authority and proscribes government agents from infringing upon freedoms retained by the people.

Just to be indisputably clear that the government is forbidden from rewriting its own delegated powers in such a way that they violate an American's God-given liberties, the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution — the Bill of Rights — act as a redundancy measure and explicit warning to state actors not to infringe upon or water down the rights delineated there.

A pure "democracy," on the other hand, can be dangerous to anyone who does not think like, or readily follow, the crowd. Villagers willing to hang a suspected horse-thief before any trial might be acting democratically, but they are still a vigilante mob. If you live in a "democracy" where everyone routinely votes to censor and imprison one another, you still live in a police state.

If too many Americans fail to fully understand why their system of government is far superior to the fickle whims that naturally poison "democracy," their representatives in government fare no better. For nearly two and half centuries, Supreme Court justices, members of Congress, and presidents have twisted and stretched the original intent and plain meaning of the U.S. Constitution. Their sometimes-questionable fealty to the very document that they have sworn to defend has done us no favors.

Given that the Founding Fathers bequeathed to us copious written records documenting their purpose in limiting the powers of the federal government as much as was practicable and safeguarding Americans' inherent liberties as clearly as possible, the sheer size of the federal government today and the breadth of its authority might shock their sensibilities. They might be horrified that a fourth branch of government — namely, the vast administrative bureaucracy — has sprung up out of whole cloth and amalgamated enormous powers once strictly separated and delegated to specific branches.

The Founding Fathers might also well be aghast not only that a vast military network emanating from the Pentagon stretches across the country but also that a distinctly fifth branch of equally powerful covert Intelligence agencies operates with black budgets, secret powers, and mostly unchecked authority. There is, after all, nothing "representative" or "democratic" about administrative agencies, defense contractors, or espionage services that exercise life-and-death prerogatives with neither the public's informed consent nor continued scrutiny.

Finally, the Founders might be both perplexed and angry that so many of Americans' rights — particularly the First Amendment's protections for free speech, freedom of assembly, and religious freedom; the Second Amendment's guarantee that every American may defend his life, home, and liberty; and the Fourth Amendment's prohibitions against unreasonable searches and seizures or the issuance of warrants without established probable cause — are under sustained attack from too many officeholders who swore oaths to defend what they apparently seek to demolish. That the clear and concise language of the Bill of Rights could be contorted to undermine the very rights that the first ten amendments to the Constitution are meant to enshrine would likely seem to the Founding Fathers both disheartening and befuddling.

It is for these many reasons that freedom-loving Americans detest the all-too-frequent pronouncements from politicians and pundits that there is nothing so sacred as American "democracy." "Democracy" means very little without well-defined limits on government power. It means even less without sure-fire protections for individual freedoms and rights.

The word "democracy" is often used interchangeably with some vague notion of the "common good." Because people with financial and political power are frequently the elite few who are actually defining the "common good" for everyone else, however, assertions of what is good for "our democracy" have a way of sounding abrasive, if not outright divisive. When "defending democracy" includes demonizing political opponents who are accused of transgressing it, those with power behave astonishingly undemocratically, themselves.

Such undemocratic behavior might include censoring accurate information to win an election, as former acting CIA Director Mike Morell testified; unconstitutional appointments for prosecuting political opponents; and repeated instances of unequal application of the law in which seemingly selective, contorted, or fraudulent prosecutions have been launched against members of the political opposition (for instance here, here and here), while reported felonies committed by members of the party in power have been waived or ignored (such as here, here, here, here, here and here).

The word "democracy" appears to have become polite shorthand for insisting that an insular minority in control of the government always knows what is best for the vast, unrepresented majority. Even worse, it sometimes seems nothing more than a convenient disguise for camouflaging abuses of power. "Democracy" may not mean the same thing as "aristocracy," "oligarchy," "empire," or "dictatorship," but in this day and age, it has sadly acquired the same peculiar aftertaste.

JB Shurk writes about politics and society, and is a Gatestone Institute Distinguished Senior Fellow.