Two weeks after a massive leak of supposedly secret US government documents, the Biden administration seems to be still unable to explain what happened let alone suggest ways of avoiding a remake of the tragi-comic incident. On closer examination, this may not be surprising, as there is still no credible account of what happened when WikiLeaks published 700,000 secret documents almost 13 years ago. However, focusing on the policing aspects of these incidents may divert attention from other more pertinent issues regarding the classification of secret documents and the use made of them by decision-makers.

To start with, the leaked documents include a large number of reports, the substance of which had already appeared in the regular media. For example, it was no surprise to learn that Ukraine does not have all the necessary weapons needed for its spring offensive against Russiai. Nor is it a scoop to learn that the US has been spying even on its allies who, we may safely assume, spy back on the US.

It is clear that too many documents are classified as secret or even top secret. This may be due to a desire by those who produce these documents to elevate their own status in the pecking order of spookdom. But it also raises the question of whether or not decision-makers would ever be able to read all these documents not to mention absorbing them. And that could create a situation in which the decision-making apparatus has all the information it needs but is unable to understand what is really going on.

Writing my book on Iran-US relations years ago I made use of more than 30 volumes of documents seized by Khomeini's "students" from the occupied US Embassy in Tehran. The volumes published by the "students" were selective samples of the treasure-trove. They showed that the CIA had more than 5,000 "sources" or "informants" across Iran and received regular reports on virtually all aspects of Iranian political, social, and economic life. But one didn't need much imagination to see that many of the so-called "top secret" documents echoed what one might have read in the Tehran newspapers or in a casual visit to the grand bazaar. The "secret" or "top secret" seals were used to raise the prestige of those who produced them. Even worse in those cases that one could trace a document's trajectory from its source up the decision-making hierarchy, it was clear that breaks and zigzags in reporting upwards prevented top policymakers in Washington from using the information provided.

Those documents, like the ones just leaked, showed another thing: the supposedly secret reports echoed the ambient mood regarding the issues involved.

In other words, the overall effect of the secret reports was to confirm what everyone assumed to be true at the time. The intelligence analyst started from an already established assumption and then tried to confirm it.

Since then we have witnessed numerous examples of that bizarre method. Right to the end, Washington's Kremlin-watchers couldn't envisage the Soviet Empire falling like a house of cards. They focused on Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika and glasnost, in other words, repeated what they had read in the newspapers. An avalanche of "top secret" reports was produced on individuals who were to become embarrassingly irrelevant figures in the blink of history's eye.

In the Iran-Iraq war, the "intelligence community" predicted a quick victory for Saddam Hussein's army: The mullahs have decapitated the Iranian army, imprisoned virtually all pilots in the air force, and sent the conscripts home with the hope that the Hidden Imam would ensure Iran's security. In the event, Saddam's Blitzkrieg lasted eight years, ending in a blood-soaked draw.

In the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, the "intelligence community" overestimated the fighting capacities of the Taliban. The cliché of the Pushtun fighter as a "human war-machine" lasted long after Mullah Muhammad Omar had fled Kabul on his Japanese motorcycle. Years later, parroting shibboleths from the intelligence community, General Stanley McChrystal, commanding NATO forces in Afghanistan, told a press conference in London that the Pushtuns had defeated all foreign invaders from Alexander to the British.

Before the Gulf War that led to Kuwait's liberation, the "intelligence community" overestimated the strength of the Iraqi army, sometimes calling it "the fourth military power in the world" and advised preparation for a long war. In the event, the whole thing was wrapped up in a few days.

President Joe Biden's disastrous withdrawal was, at least in part, prompted by overestimating the solidity not to say the loyalty of the Afghan army under President Ashraf Ghani.

This was an army with the most modern weapons systems in the neighborhood and led by officers trained in prestigious US academies. What the spooks didn't report was that for more than a year before the final collapse, a growing number of that army's officers and NCOs were sending their money and their families abroad. Ghani did even better by launching a scheme under which even private Afghan citizens could leave the county with up to $10,000 in each trip. As the last American troops flew out of Kabul, there was no one to turn the lights off in all those posh barracks and arms depots built with billions of dollars from the American taxpayers' pockets.

The same intelligence community reported Russia's saber-rattling over the Crimean Peninsula as mere gesticulation by President Vladimir Putin in the context of the power struggle in Kyiv, presumably to endorse President Barack Obama's decision not to enter a fight with the Russians. When Putin did invade and occupy the peninsula in 2014, Obama tried to weasel out of a tight corner by declaring that Russia was a "regional power" and that its actions on its own were not a US "national security concern".

The intelligence community tailored its "top secret" reports to suit Obama's naïve analysis, effusively giving Putin the green light for his second invasion of Ukrainian territory over a year ago. The same reports overestimated Russia's military power, ignoring the fact that much of its weaponry consisted of antiquated hardware inherited from the Soviet era.

The intelligence community got it right when it predicted Putin's invasion last year. But that prediction did not result in Washington decision-makers shaping policies to deal with the crisis.

Maybe decision-makers would have done better to read the newspapers, rather that the "top secret" memos they received and ignored.

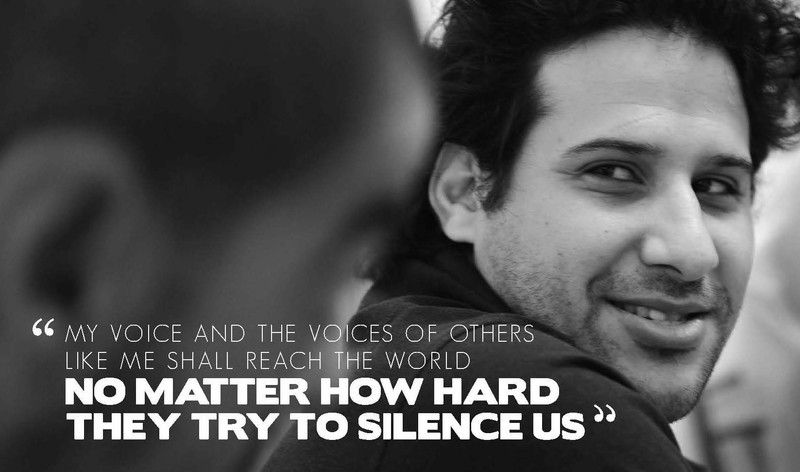

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article originally appeared in Asharq Al-Awsat and is reprinted by kind permission of the author.