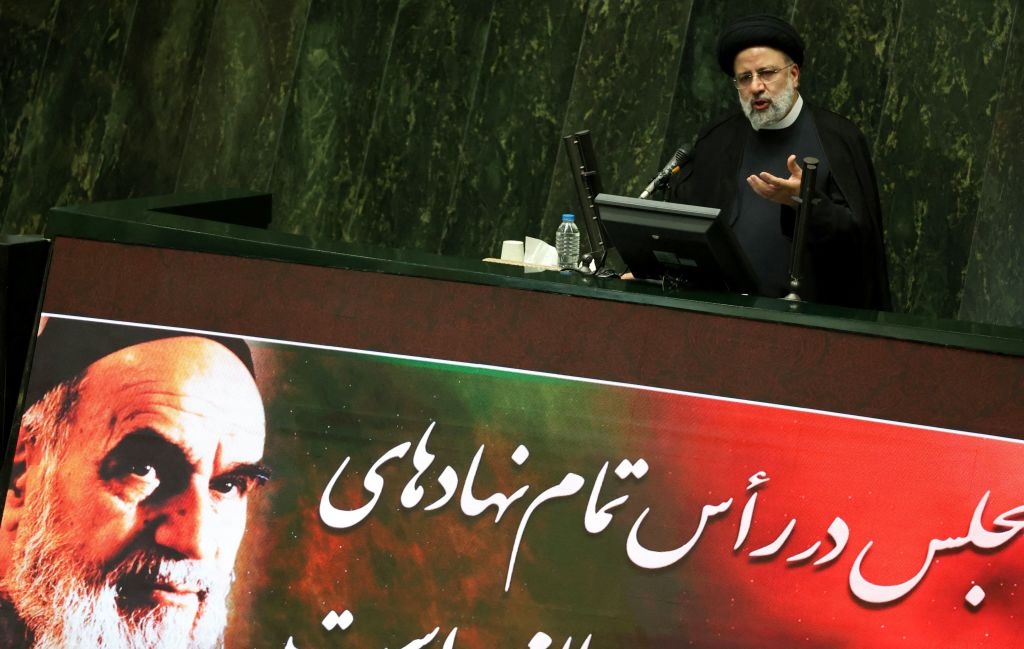

It would be interesting to see how the Biden administration plays an unexpectedly strong hand it now holds against the Iranian regime that claims "the end of America" as its strategic goal but secretly hopes that the "Great Satan" will help it get out of the historic black hole dug by a weird ideology. Pictured: Iran's President Ebrahim Raisi speaks before parliament in Tehran on August 25, 2021. (Photo by Atta Kenare/AFP via Getty Images) |

"Return to the nuclear talks!" This is the advice that China, France and Russia have been publicly giving to Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi's new team in Tehran since they assumed power last month. Other powers, notably Germany, have echoed that advice in private. There are signs that the new Raisi team may be listening to that advice or, at least, trying to prepare public opinion for a return to Vienna with its flag in its pocket.

Raisi, who had once dismissed any negotiations with big powers as "out of the question," now says he always regarded negotiations as "one instrument of policy."

Several developments have contributed to what seems a less belligerent stance by Tehran.

The first is that the Biden administration seems extra-keen to deal with what it regards as an "underbrush" issue at a time that the new US president wants to disengage from the Middle East and focus on the Asia-Pacific, the main theater of rivalry with China.

The fact that Biden is the first US president in 40 years not to have downgraded the Arab-Israeli issue, not appointing a special point man for it, is seen in Tehran as one sign of the tectonic shift in American global strategy. The withdrawal from Afghanistan, likely to be followed by disengagement in Iraq, is seen as another sign.

Another factor is Biden's refusal to help the "New York Boys" faction in Tehran by offering a deal that might have saved then President Hassan Rouhani's faction from obliteration last spring.

More importantly, perhaps, both China and Russia have made it clear that unless the nuclear issue is settled, they would not enter any strategic partnership with the Islamic Republic. Keen to see the US reduce its footprint in the Greater Middle East, both Moscow and Beijing believe that Tehran's anti-American posture and hostility towards Israel may make it more difficult for Washington to proceed with its current plans for the region.

Domestic issues are also putting pressure on the mullahs to reach an accommodation with the "Great Satan". With the economy in poor shape as annual inflation rate tops 50 percent while the national currency hits new lows every week, Tehran badly needs the easing of some sanctions. This is why Raisi no longer demands a lifting of all sanctions.

Another factor that forces Raisi and his team to alter their defiant posture is the catastrophic situation created by the Covid-19 pandemic. Even regime apologists admit that "Supreme Guide" Ali Khamenei's initial ban on importing vaccines may have claimed tens of thousands of lives. Thus, a minimum of normalization is needed to tame the pandemic and deal with its economic and social consequences.

The pandemic, along with economic meltdown and factional feuds within the establishment, have also encouraged a wave of protests across the country, protests that in some cases the regime's security forces were unable to cope with.

The Raisi team is also worried about a revival of armed struggle by regime opponents. In recent weeks, armed attacks in areas along Iran's northwestern borders have fomented a sense of insecurity in at least three provinces. Tehran seems to have been worried enough to dispatch Gen. Pakpur, Commander of the Land Forces of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to the affected area with a warning that if attacks continue, the IRGC will take action against the autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq where anti-Tehran armed groups are located.

Visiting the area a day later, another IRGC general, Arjomandi Far, claimed that anti-regime armed groups may have bases in three of Iran's northwestern borders: Iraq, Turkey and (former Soviet) Azerbaijan.

The latest developments in Afghanistan also contribute to Tehran's current anxiety over across-the-border threats. So far that threat has come from dissident groups based in Pakistan while the US presence prevented the shaping of such a threat in Afghanistan.

The current anxiety in Tehran may provide an opportunity for the Vienna talks to be expanded beyond the chimeric issue of Iran's nuclear ambitions. Concern about what Tehran might do if and when they make a bomb need not exclude concern about the mischief it is doing across the Middle East, notably in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen and, of course, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Right now the Islamic Republic in Tehran is at its most vulnerable position in decades. That is a fact that some even within the regime are beginning to understand. This is why the idea of withdrawing from Syria and the futility of prolonging the war in Yemen, for example, is no longer taboo.

The Biden administration could use the Vienna talks in pursuit of three ways.

The first is to make an offer the mullahs cannot refuse. If the US could make a deal with erstwhile foes in Afghanistan, why not do something similar with Iran?

That comparison, however, is flawed. Anti-Americanism was never the ideological bread-and-butter either of the Afghan Mujahedin or the Taliban that appeared later to claim the jihadi mantle.

The second option is to offer the mullahs an offer they cannot accept. But that would force the US to adopt regime change in Tehran as its main objective in dealing with Iran. And that, of course, would require a continued and stronger US presence in the region, not withdrawing to focus on Asia-Pacific.

The third option is to regularize the status quo which, when all is considered, although it has not forced the mullahs into full surrender has, nevertheless, sharply reduced their mischief-making capabilities.

Right now, all three options seem to have some supporters within the Biden administration and among regional and European allies.

The important thing is that, for the first time since President Barack Obama allowed the mullahs to seize the initiative, it is the US that can set the tune. Tehran's relations with all neighbours of Iran and countries such as China, India and Russia that could throw a lifesaver to a drowning regime are also tangentially linked to its relations with the US.

It would be interesting to see how the Biden administration plays an unexpectedly strong hand it now holds against a regime that claims "the end of America" as its strategic goal but secretly hopes that the "Great Satan" will help it get out of the historic black hole dug by a weird ideology.

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987.

This article was originally published by Asharq al-Awsat and is reprinted by kind permission of the author.