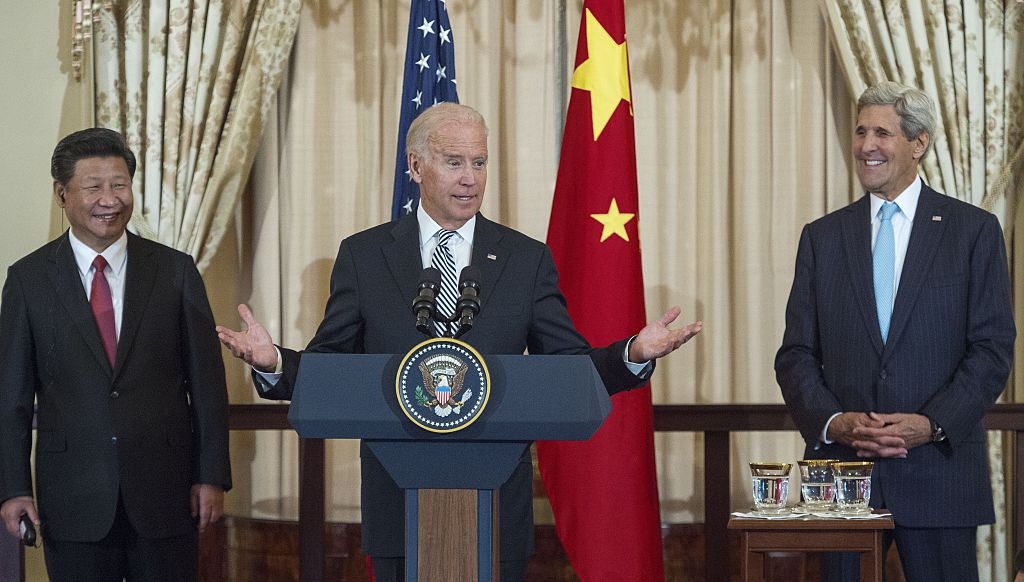

At least for the moment in Washington, DC, negative comments about China are out and cooperative words are in. But President Joe Biden had it right last February, when he called China's President Xi Jinping a "thug." Leaders of democracies, despite all the good will in the world, will find they cannot cooperate with thugs. Pictured: Xi (left) and then US Secretary of State John Kerry (right) listen as then Vice President Biden speaks in Washington, DC on September 25, 2015. (Photo by Paul J. Richards/AFP via Getty Images) |

"I was asked a long time ago when I was with Xi Jinping," said President Joe Biden in his first hours in office, as he swore in officials, "and I was on the Tibetan plateau with him, and he asked me in a private dinner he and I and we each had an interpreter he said can you define America for me, and I said yes and I meant it. I said I can do it in one word, one word: possibilities. We believe anything is possible if we set our mind to it, unlike any other country in the world."

In Beijing, Communist Party leaders must be ecstatic. For one thing, during the 10-minute ceremony Biden mentioned no other country.

Moreover, ruler Xi Jinping will think the Tibetan plateau reference significant. Biden's words, after all, came one day after then Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued a determination that China was committing crimes against humanity, including genocide, against minorities. Pompeo's declaration presumably includes the minority Tibetans. Beijing is suppressing them in many of the same ways as it is liquidating Uyghurs, the focus of his historic statement.

Xi and other Chinese leaders will doubtless take Biden's fond recollection as a sign the new president is not serious about China's atrocities against minority peoples.

As Hong Kong's South China Morning Post reported, "Biden's reference to China's leader in the form of a memory, and devoid of any negative comments about bilateral conflicts, marks a departure in tone following four years of escalating tensions between the administration of former President Donald Trump and Beijing."

At least for the moment in the American capital, negative comments about China are out and cooperative words are in. This new approach, a sharp break from that of the second half of the Trump administration, is outlined in an influential article on the website of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

In "Four Principles to Guide U.S. Policy Toward China," the Atlantic Council's Ali Wyne suggests a weakened America needs to accommodate the People's Republic of China. Washington, Wyne argues, most certainly should "Strive for a Durable Cohabitation," his fourth principle.

In reality, cohabitation is impossible to achieve.

Why impossible? The answer lies in Wyne's befuddlement, an ailment generally afflicting the establishment foreign policy community in America.

Wyne ponders why Beijing last year did not take advantage of the pandemic to implement generous policies the world would have heartily applauded. Instead, Chinese officials missed an historic opportunity to extend influence by engaging instead in belligerent "Wolf Warrior" diplomacy.

The Atlantic Council scholar suggests two reasons for Beijing passing up this chance -- "diplomatic self-sabotage" he calls it. "First, the Chinese Communist Party felt pressure to deflect attention away from external criticism of its response to the pandemic," Wyne writes. "Second, party leaders believed that the United States's domestic preoccupations gave China a window in which to advance its interests in the Asia-Pacific more forcefully."

In reality, the reason China passed up that opportunity to extend influence can be found in the core of Chinese communism. China's communist system is inherently belligerent and fragile, which means it cannot engage in the type of diplomacy Wyne correctly believes would be in its interest.

Wyne should have consulted Minxin Pei before penning his piece. "A liberal internationalist foreign policy is incompatible with China's illiberal domestic order," Pei wrote when he was at the Carnegie Endowment. "Although an illiberal regime can occasionally demonstrate tactical brilliance in diplomacy, its execution of a constructive, long-term foreign policy will be undermined by the character flaws inherent in autocracies: insecurity, secrecy, intolerance, and unpredictability."

It is no coincidence that Beijing's only formal ally is the insecure, secretive, intolerant, and unpredictable Democratic People's Republic of Korea -- and even these two neighbors do not get along well.

China also cannot get along with the United States, which maintained China-friendly policies for more than four decades. In fact, People's Daily, the most authoritative publication in China, in May 2019 carried a piece that declared a "people's war" on America. The declaration was one in a series of especially belligerent Chinese propaganda pieces that month.

China's "unrestricted warfare" on the United States has taken a toll. Recently, Chinese leaders deliberately spread the coronavirus beyond their borders, making deaths in America mass murder as well as "genocide," as that term is defined by Article II of the 1948 Genocide Convention.

Beijing in recent months has engaged in extremely provocative acts, such as using the now-closed Houston consulate to provide logistical and financial support to violent protesters in America.

A Radio Free Asia report tells us a People's Liberation Army intelligence unit, working out of that consulate, used big data to identify Americans likely to participate in Black Lives Matter and Antifa protests and then sent them videos on how to organize riots.

China even incited violence in the open last year. On October 18, Chen Weihua, China Daily's European bureau chief, tweeted : "Hope there will be more petrol bomb throwing mobs in protests in the U.S."

Moreover, in late January of last year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents in the International Falls Port of Entry in Minnesota seized 900,000 counterfeit $1 bills, made in China.

Nobody, in China's near-total surveillance state can counterfeit American currency without authorities knowing about it. This counterfeiting operation, in all probability, had Beijing's blessing. We do not know the motive for this crime, but it could not have been for profit. Who counterfeits $1 bills? Yet whatever the reason, counterfeiting another country's currency is considered an act of war.

Also, in May of last year, U.S. authorities in Louisville seized assault weapons parts smuggled in from China, almost surely an attempt to promote violence.

In addition, China's regime steals hundreds of billions of dollars of American intellectual property annually, engages in predatory trade practices against U.S. companies, interferes in American elections, and confronts the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force in the global commons. Beijing has even been so bold as to cause brain injuries to American diplomats at the Guangzhou consulate.

Wyne does not write about these acts of aggression. Instead, he points out how bad the Washington-Beijing relationship is -- it has "morphed from one of competitive coexistence into one of systemic antagonism" -- and tells us there is an "urgent undertaking" for Washington "to pursue a sustainable modus vivendi" with China.

Yes, the need looks urgent, but just because something is urgent and needed does not make it possible. The United States must look at the situation as it is and stop searching for a Chinese regime that is not as Wyne wishes it to be.

That brings us back to Biden. He had it right last February. While trying to win his party's presidential nomination, he then called Xi Jinping a "thug."

Leaders of democracies, despite all the good will in the world, will find they cannot cooperate with thugs.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China, a Gatestone Institute Distinguished Senior Fellow, and member of its Advisory Board.