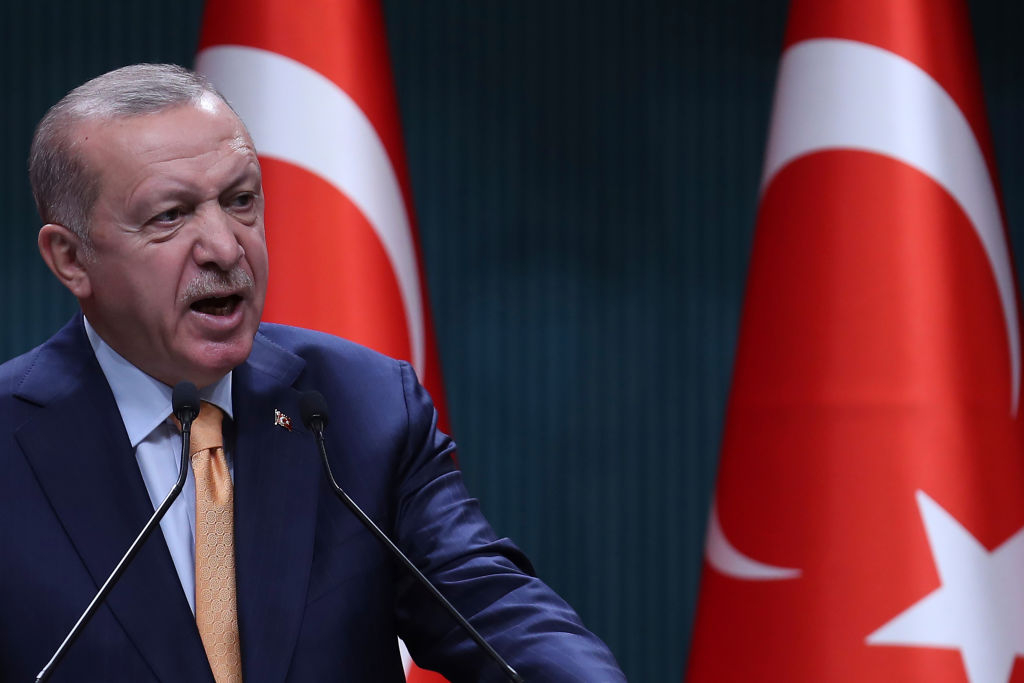

The Turkish government has, in recent years, escalated its rhetoric of neo-Ottomanism and conquest. On August 26, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave a speech in which he said: "Turkey will take what is its right in the Mediterranean Sea, in the Aegean Sea, and in the Black Sea." Pictured: Erdoğan in Ankara on October 5, 2020. (Photo by Adem Altan/AFP via Getty Images) |

The Turkish government has, in recent years, escalated its rhetoric of neo-Ottomanism and conquest.

On August 26, for instance, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave a speech at an event celebrating the 949th anniversary of the Battle of Manzikert. This battle resulted in Turks from Central Asia invading and capturing the then majority-Armenian city of Manzikert, within the borders of the Byzantine Empire.

Parts of his speech were translated by MEMRI:

"In our civilization, conquest is not occupation or looting. It is establishing the dominance of the justice that Allah commanded in the [conquered] region.

"First of all, our nation removed the oppression from the areas that it conquered. It established justice. This is why our civilization is one of conquest.

"Turkey will take what is its right in the Mediterranean Sea, in the Aegean Sea, and in the Black Sea. Just as we are not eyeing the soil, sovereignty, or interests of anyone else, we will never give any concession from ours. This is why we are determined to do whatever is necessary politically, economically, or militarily. We invite our interlocutors to put themselves in order and stay away from mistakes that will open the way for them to be destroyed.

"We want everyone to see that Turkey is no longer a country whose patience is to be tried or whose determination, capabilities, and courage are to be tested. If we say we'll do it, then we will. And we will pay the price.

"If there is anyone who wants to stand against us and pay the price, let them come. If not, let them get out of our way, and we will see to our own business.

"And what did [Turkish poet] Yahya Kemal say? In the spirit of the armies here: 'This storm breaking out is the Turkish army, oh Lord! The army that dies for your sake is this one, oh Lord! May your renowned and strengthened name be raised up with the calls to prayer! Make us the victor, because this is the last army of Islam! '"

In another speech in May, Erdogan again commented on conquests, referring to the 1453 invasion of Constantinople by Ottoman Turks:

"Our ancestors saw the conquest not only as the seizure of lands, but as the winning over of hearts. Recently, some presumptuous people have tried to define the conquest as occupation. Believe me they are completely ignorant. Ask them what conquest means and they will not know. Conquest is to open [things]. Conquest is especially to win hearts, but they do not know this. Our ancestors, starting a thousand years ago, first embroidered every part of Anatolia, Thrace, and the Balkans through alperens [combatants], dervishes, veterans.... As the Conqueror [Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II] entered through the walls of Istanbul, the Greek ladies said, 'We wish to see an Ottoman turban rather than see the cardinal cone on our heads.'"

One of Turkey's major problems is systematic historical revisionism promoted by the government and all other institutions in the country, including the media. There are significant falsehoods in this revisionism, particularly about the invasion of Manzikert (Malazgirt) and of Constantinople (Istanbul).

When Turks, led by Sultan Alp Arslan (real name: Muhammad bin Dawud), arrived in Manzikert in the eleventh century to invade the region, they did not "win hearts." Instead, they committed massacres. Manzikert was then a predominantly Armenian city. The massacre "began in 1019—exactly one-thousand years ago," writes historian Raymond Ibrahim, "when Turks first began to pour into and transform a then much larger Armenia into what it is today, the eastern portion of modern day Turkey."

As Ibrahim describes, the conquests were not achieved by "the winning of hearts." They were accompanied by brutal slaughters of Christian natives, captivity of women, girls and boys and destruction of churches.

"The most savage treatment was always reserved for those visibly proclaiming their Christianity: clergy and monks 'were burned to death, while others were flayed alive from head to toe.' Every monastery and church—before this, Ani was known as 'the City of 1001 Churches'—was pillaged, desecrated, and set aflame. A zealous jihadi climbed atop the city's main cathedral 'and pulled down the very heavy cross which was on the dome, throwing it to the ground,' before entering and defiling the church...

"Not only do several Christian sources document the sack of Armenia's capital—one contemporary notes that Muhammad 'rendered Ani a desert by massacres and fire'—but so do Muslim sources, often in apocalyptic terms: 'I wanted to enter the city and see it with my own eyes,' one Arab explained. 'I tried to find a street without having to walk over the corpses. But that was impossible.'"

Another historical fact involves the atrocities committed during the invasion of Byzantine Greek city of Constantinople by Ottoman Turks in the fifteenth century. The claim that Greek women said "they preferred Ottomans" cannot be further from the truth. The city actually fell after several weeks of Greek resistance. Historian Mark Cartwright writes that "the Byzantines were hopelessly outnumbered in men, ships, and weapons."

When Constantinople was invaded on May 29, 1453, adds Cartwright, "the rape, pillage, and destruction began."

"Many of the city's inhabitants committed suicide rather than be subject to the horrors of capture and slavery. Perhaps 4,000 were killed outright, and over 50,000 were shipped off as slaves. Many sought refuges in churches and barricaded themselves in, including inside the Hagia Sophia, but these were obvious targets for their treasures, and after they were looted for their gems and precious metals, the buildings and their priceless icons were smashed, the cowering captives butchered. Uncountable art treasures were lost, books were burned, and anything with a Christian message was hacked to pieces, including frescoes and mosaics."

The fall of Constantinople brought an end to the Byzantine Empire and led to the takeover of the region by the Ottoman empire. The history of Ottoman Turks was also largely marked by persecution against Christians and other non-Muslims.

The Ottoman Empire lasted for some 600 years (from 1299 to 1923) and included parts of Asia, Europe and Africa. Christians and Jews under the Ottoman rule became dhimmis, second-class "tolerated" subjects, who had to pay a heavy jizya protection tax to stay alive. During this period, as historian Vasileios Meichanetsidis notes, the Turks engaged in oppressive practices, including:

- "the ghulam system, in which non-Muslims were enslaved, converted and trained to become warriors and statesmen;

- the devshirme system, the forced recruitment of Christian boys taken from their families, converted to Islam and enslaved for service to the sultan in his palace and to join his janissaries (new corps);

- compulsory and voluntary Islamization -- the latter resulting from social, religious and economic pressure; and the sexual slavery of women and young boys, deportation and massacre."

Many Turkish beliefs about history are actually the complete opposite of historical truth. According to the Turkish study of history, for instance, what happened in Ottoman Turkey in 1915 was not genocide against Armenians. Turkey's Institute of History has produced a documentary in five languages about what it calls, "The Armenian rebellion against the Ottoman state, terrorism and propaganda." The documentary – in line with how the Turks study history – falsely claims that it was Armenians who attempted to massacre Turks and commit other crimes against them and that Turks only acted in self-defense. Most objective historians, however, conclude that the events of 1915 constitute genocide against Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks.

This revisionism in which Turkey engages is not only an insult to the victims of these crimes and to the descendants of the victims, but also a barrier that prevents many Turks from developing critical thinking and an understanding of empirical facts. A belief in jihad [holy war in the name of Islam], conquest in the name of Islamic doctrine and the dehumanization of kafirs (infidels) seem to play a large role in Turkish supremacist mentality and its leaders' current aspirations. In 2016, for example, Numan Kurtulmus, the then-deputy prime minister of Turkey, announced at a public meeting, "Independence means being able to stand up to kafirs (infidels) by calling them kafirs." In 2018, the Speaker of Turkey's parliament, İsmail Kahraman, described Turkey's military offensive against northern Syria as "jihad." "Without jihad," he added, "there will be no progress." During the same offensive, Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) also called for "jihad" and declared in a weekly sermon that "armed struggle is the highest level of jihad."

Many Turks, therefore, still glorify Seljuk, Ottoman and Turkey's invasions and trivialize or deny altogether the crimes committed. Turkey's 1974 invasion of Cyprus, for example, was accompanied by many crimes such as murders, rapes, torture, seizure and looting of properties and forced disappearances of Greek Cypriots. The Turkish government nevertheless officially calls the invasion a "Cyprus Peace Operation" and every year proudly commemorates it.

Hate speech is also widespread in Turkish media. According to a report by the Hrant Dink Foundation, Armenians were the group most targeted by hate speech in Turkish media in 2019, followed by Syrian refugees, Greeks and Jews.

When massacres and other atrocities are systematically referred to as "glorious events," and ongoing human rights abuses – such as the incarceration by Erdogan of political prisoners become socially normalized incidents, it should not come as a great surprise that most Turks do not raise their voices against grave human rights violations in the country or Turkey's continuing occupation of northern Cyprus or Syria.

Uzay Bulut, a Turkish journalist, is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute.