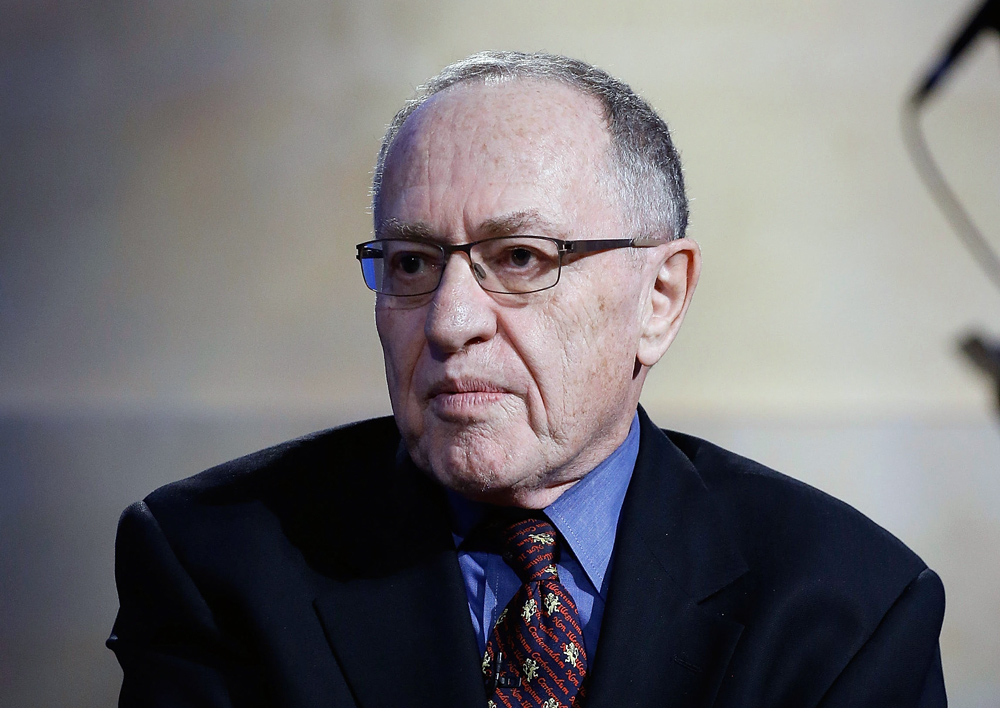

Alan Dershowitz. (Photo by John Lamparski/Getty Images for Hulu) |

Saturday was the 69th anniversary of my bar mitzvah. To celebrate it, my son videotaped me chanting from the same Torah portion I chanted 69 years ago in the Young Israel of Boro Park. The words I intoned were written three thousand years ago. And yet not a single revision is required to make them relevant to today's world.

My portion begins with a command to the Israelites to "appoint judges and magistrates in all your cities." The judges are then commanded not to pervert justice by showing favoritism or taking bribes, "for bribery blinds the eyes of the wise and perverts just words."

Then comes the central command, perhaps of the entire Torah: "Justice, justice must you pursue." Actually, the word pursue is not as strong in the English as it is in the Hebrew. The Hebrew word "tirdof" literally means to chase or run after. It is as if God was telling his people that the quest for justice never stays won. It must always be actively pursued. No one can ever rest satisfied that justice has been achieved.

Think of that demand for active justice in the face of the racial injustice that had plagued our country since its founding. In the 1940s, many thought that racial justice had been achieved when the army was integrated. In the 1950s, we thought that justice had been achieved when the Supreme Court ordered desegregation of the public schools. In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act promised equal justice.

In every generation, the quest for justice has achieved better and better results. There is far more racial justice today than ever before in our history. But no one looking at today's America can rightfully conclude that we have achieved ultimate justice for African-Americans. The same is true of other disadvantaged and discriminated-against groups. We are on a road that never ends.

We must never be content with the status quo, certainly as it regards justice. There is a line in the Merchant of Venice that implicitly makes this point. Shylock has been forced to convert on threat of death. When he is asked whether he has truly converted from Judaism to Christianity, he replies "I am content." I have always thought that his answer proved beyond a doubt that he was no longer a Jew.

Because no Jew is ever content. It is not in the nature of Jews to be content and it is not in the nature of anyone who believes in the Bible to be content with the current state of justice.

The commentators on the Bible frequently ask why God repeated the word "justice"? Wouldn't it have been enough for Him to command, "Justice must you pursue?" But no: God says, "justice, justice."

There are no extra words in the Bible. Every word has a meaning. So various commentaries have been offered in the meaning of the duplication. Some say that one reference is to substantive justice while the other is to procedural justice. Others say that one justice is for the victim, and the other for the accused.

Still others say that there is no single definition of justice: we know injustice when we see it, but there is no agreement about what constitutes perfect justice. It is in the nature of biblical commentary that it never ends. Every generation comes up with new interpretations and new insights as to the meanings of ancient words.

I was fortunate to have my bar mitzvah fall on the week in which this particular biblical portion is read by Jews all around the world. I always believed that it sent me a message. I have devoted my life to seeking justice for others, from my earliest opposition to the death penalty while I was in high school to the current pro bono work I do with Aleph, the wonderful Chabad organization that provides services to imprisoned men and women all over the world.

Now, at 82, I am demanding justice for myself. I have been falsely accused by a woman I never met of having sex with her. I have already achieved justice in terms of the evidence that conclusively proves to any open-minded person that it is impossible that I would or could have done what she falsely accused me of.

Indeed, the best evidence of my innocence is in her own words: a series of emails and manuscript that she tried to suppress in which she essentially admits that she never met me. Her lawyer's own words -- she is "wrong... simply wrong" in accusing you -- constitute an admission attributable to her.

Another of her lawyers has acknowledged that she lied about other prominent men. She told her best friend and her best friend's husband that she was pressured by her lawyer to falsely accuse me. You would think that would be enough. But no, not in the age of cancel culture and #MeToo, where evidence and lack thereof count for little.

What is most important in this age of identity politics is the identity for the accuser and the accused: Always believe women, regardless of their history of lying; or regardless of the accused's history of truth-telling and sexual probity.

The Bible teaches otherwise. In my portion, judges are directed not to take identity into account. The words in Hebrew are "Lo takir panim," which means do not base your decision on the faces or identities of the litigants. Base it instead on the facts and the evidence. I wish people today would abide by that 3,000-year-old wisdom.

I also wish judges and prosecutors paid more heed to another command of my Bible portion: "The judges shall inquire diligently; and behold if the witness be a false witness and has testified falsely against his brother, then shall ye do unto him as he had proposed to do unto his brother..." I have invited prosecutors and judges to "inquire diligently" into my accuser and me. If they do, they will conclude that she has "testified falsely" and should be punished under the law of perjury.

I, for one, will continue to live and work in the spirit of the commandment to chase after "justice, justice." Justice for those who have been sexually exploited. And justice for those who have been falsely accused -- as Joseph in the Bible was -- of sexual misconduct. I am confident that justice and truth will prevail in my case, no matter how long the road or how exhausting the chase.

The writer is the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law, Emeritus at Harvard Law School and author of Guilt by Accusation: The Challenge of Proving Innocence in the Age of #MeToo, Skyhorse Publishing, 2019. He is the Jack Roth Charitable Foundation Fellow at Gatestone Institute.

This article was originally published in The Jerusalem Post and is reprinted here by the kind permission of the author.