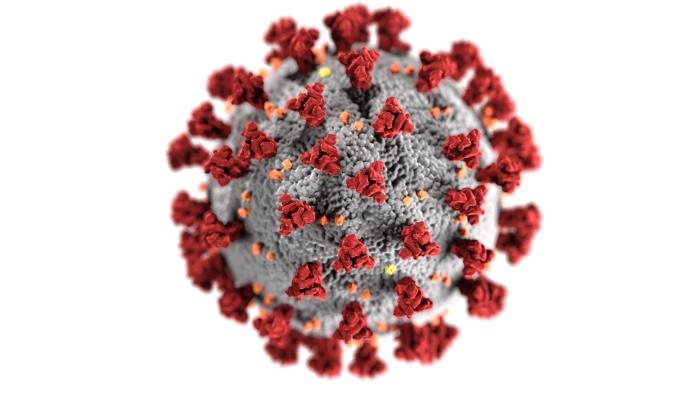

Even though modern science will prove the only path to the prevention or cure of Covid-19, millions of people have approached illness and fear of death through faith, prayer, and ritual. Pictured: The ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. (Image source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) |

Religious communities around the world have gone through a multitude of responses to the global Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, which has inflicted lasting damage to most nations. Lives have been lost, economies have been undermined, and more might still be to come. Scientists have responded with a range of rational rejoinders to the challenge the virus poses. They have been carrying out research to find testing, treatments and a vaccine.

Not everyone, however, is a rationalist. Even though modern science will prove the only path to prevention or cure, millions have approached illness and fear of death through faith, prayer, and ritual. Many have practiced their faith quietly while observing the recommendations of scientists and governments. Churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, shrines and other faith centers have been closed or have continued to operate through videoconferencing. The largest of these closures was the Saudi kingdom's decision to postpone the annual once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca.

Some Christians, Jews and Muslims have been less responsible, insisting on breaking the rules that apply to whole populations, including their own. For these believers, it might be the intensity of their faith (being saved by Allah or the blood of Jesus) or the need to retain a continuity with sacred traditions, such as mass funerals to show respect for the deceased that drives them to persist in dangerous practices.

Many Muslims, thinking responsibly, have closed mosques in the West or, as mentioned, cancelled the hajj in Mecca. In northern England, for instance, the Newcastle Central Mosque has set up a support group for vulnerable people in the wider community, complete with aid packages and shopping for people in isolation.

Elsewhere, sadly, many have reacted to the pandemic in much less positive ways. Broadly speaking, Muslims globally seem to be finding it difficult to embrace modernity. Writing in Pakistan's Express Tribune, journalist Khaled Ahmed proposed:

"It is often said that Muslims in the 21st century have rejected modernity. What they are in fact rejecting is the process of suiting themselves to changing circumstances. There are two kinds of thinking: one that seeks to change in order to relate to times and one that seeks to change the world to suit its tenets."

One consequence of this anti-modernity position is that it can involve a suspicion of modern science and medicine. This view that can lead to a refusal to accept Western understanding of illnesses such as coronavirus, and that conclusion can take millions to dangerous interpretations of what the epidemic really is. As the coronavirus spread within Muslim countries such as Iran or Pakistan, it was no longer possible to deny the reality of the global affliction. This in itself might have presented a psychological problem for radicals and traditionalists. Does the voracity of the disease mean, to them, that Muslims are no different from non-Muslims in their vulnerability to the disease? Or that coronavirus is a punishment from God that affects Muslims as well as unbelievers? Or that the disease struck those who probably did not practice their faith zealously enough?

None of these options might sit well with the widespread Islamic doctrine that Muslims are God's favoured people, devotees of Muhammad, the divinity's last prophet, and his last scripture, the Qur'an. To avoid that dilemma, many Muslims might resort to an even broader rejection of modernity, one that has grown sharply in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

In earlier centuries, from 634, Muslim empires conquered and ruled wide parts of the world, most before the advent of modern Western countries. The Ottoman Empire stretched from what is now Turkey across the Middle East, Egypt, all of North Africa, the Balkans, and much of Spain and Portugal. At all times since the death of Muhammad in the seventh century, it has been a fundamental doctrine in Islamic law that any territory, once conquered for Islam, must remain under Muslim rule in perpetuity. By the nineteenth century, nevertheless, some Muslim territories were passing out of overall Islamic control. The British ended the cultivated Mughal Empire in India. Iran fought wars with Russia and in the 20th century came under divided Russian and British influence. The vast Ottoman Empire was defeated by the allies in World War I, and the last of the great caliphates was abolished by the newly-formed secular Republic of Turkey in 1922.

Some Muslim reformers chose to adjust to this new world, but as decades passed, and with the development of hard-line radical Islam accompanied by oil wealth from the 1970s, so grew an increasingly outspoken resentment of the West. Muslim states, such as Turkey, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, found it hard to function as nation states under democratic rule. The establishment of Israel in 1948, in what had previously been part of an Ottoman province, led to at least four wars to dislodge and displace it, as well as more than 70 years of terrorism.

It may well have been within this context that radical and traditionalist Muslim preachers and politicians leaped on the coronavirus pandemic as a new modality of their crusade against the West. Iran, for instance, has blamed the virus on America and Israel. Many articles and social media in the Arab world, parroting China's disinformation, claim that Covid-19 was created by the United States in order to topple the economy of China, its rival. Al-Qa'ida Central insists that the coronavirus is divine punishment for the sins of mankind and that Muslims must repent while the West must embrace Islam. Extremists in the Islamic State (ISIS) group and al-Qa'ida seem to see the upheaval caused by the virus as an opportunity to gain recruits and strike harder using terrorism. One Salafi-Jihadi ideologue, Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi wrote online that:

"There is nothing wrong with a Muslim praying for the deaths of infidels and wishing that they contract coronavirus or any similar fatal disease."

İbrahim Karagül, the editor of the Turkish newspaper, Yeni Safak, which has a close relationship with the country's ruling AKP party, euphorically wrote:

"It seems that everything produced and imposed to the world by the West in the form of a global discourse and order is coming to an end. The West has already lost its 'central' power.... The West's financial system is collapsing. Its political system and discourse are collapsing. Its security theories are collapsing. Its social theories are collapsing. Humanity no longer has any expectation of them.... New superpowers will emerge.... If there are going to be any countries to rise post-corona – and there will be – Turkey is going to be one of them."

The Middle East Research Institute (MEMRI) has posted dozens of similar responses from Muslims online. Readers might start here.

Dr. Denis MacEoin, a specialist in Iranian Studies, is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at New York's Gatestone Institute.