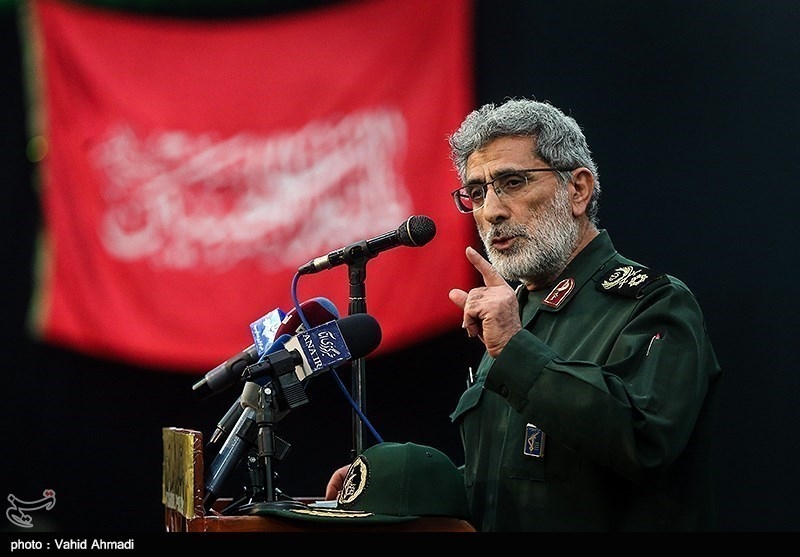

Esmail Ghaani, Qassem Soleimani's successor as head of Iran's Quds Force, has promised: "to continue martyr Soleimani's path with the same force and the only compensation for us would be us would be to remove America from the region." (Image source: Tasnim News [CC by 4.0]) |

When news broke on the morning of January 3 that Qassem Soleimani, an Iranian general who for many years had headed the Quds Force, the powerful extraterritorial operations arm of the regime's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), had been assassinated -- along with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, head of the Iraqi Ketaib Hezbollah militia -- in a US drone strike at Baghdad airport, pundits across the globe burst into print, some to condemn, others to praise his killing.

Neither side seems to want an all-out war. On October 7, 2019, US President Donald J. Trump tweeted:

"... it is time for us to get out of these ridiculous Endless Wars, many of them tribal, and bring our soldiers home. WE WILL FIGHT WHERE IT IS TO OUR BENEFIT, AND ONLY FIGHT TO WIN."

One can only hope that this statement is not as un-thought-through as it appears. While in a democracy war is never a first choice -- least of all in an election year -- the Western fight against Islamist terrorism and territorial predation is far from at an end. As President Trump has already found out in both Syria and Iraq, when it was even mentioned that troops might be withdrawn, evidently that was understood by some countries as an invitation to help themselves, and more troops had to be sent, often within days. The same "misunderstanding" might be now be taking place in the waters of the eastern Mediterranean and Libya as well.

Quite often, troop deployment in these areas does not so much mean "endless wars" as forward deployment. While President Trump is indeed a dazzling negotiator, there are sizeable differences between negotiating, say, business deals and geopolitical ones. Business deals tend to be "win-win": You have the land and I have the money, or I have the land and you have the money. Geopolitical deals can be stickier: You would like to have -- nuclear weapons capability? The Middle East? Control of all the sea lanes on the planet? What is supposed to disabuse a despot of his wish? Will a despot cheat? Will a despot take money given to him not to cheat and use it to cheat? Why would a despot not cheat? Or try to?

So much terrorism has come from Tehran. The Iranian regime works across the Middle East, using major terrorist forces such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria, Hamas in Gaza, Houthi rebels in Yemen, and Soleimani's Revolutionary Guards Quds Force in Syria, Iraq and as distant as Latin America.

Iran may be chary of waging full-out war, and has been seeking negotiations -- at the United Nations. Evidently the mullahs have calculated that they have too many expensive assets to lose, starting with oil refineries. The regime has been weakened of late by US sanctions, conflict in the Gulf, the main waterway for its oil, and by unrest at home, often put down with savage force. Nevertheless, threats and attacks are likely to keep on developing for months if not years. The assassination of Soleimani is, by any standards, a game-changer. Even as his body was taken on a tour of cities in Iran, to reach his burial site in his native Kerman:

"The Islamic Republic will no longer observe any limits on the operational aspects of its nuclear program," the semi-official Fars news agency reported Sunday, citing a statement from the government.

The Iraqi parliament has, in a non-binding resolution, called for the withdrawal of the 5,000 US troops stationed in the country during the campaign against Islamic State. Meanwhile, Mohsen Rezai, a former Revolutionary Guard chief has declared: "If [US President Donald] Trump retaliates to Iran's revenge, we will strike Haifa, Tel Aviv and wipe out Israel".

Rash words, of course, though not at all surprising from a representative of a state that daily chants "Death to Israel" in defiance of all international norms and laws, ironically at the UN, where Iran is now seeking negotiations. The UN Charter expressly prohibits member states from threatening one another:

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations. – UN Charter, Article 2(4)

One might also ask why has the United Nations never held Iran accountable for these violations? One might also ask if the time has finally come for the UN's largest donors -- read the US -- to rethink their generosity? Why not, as Ambassador John R. Bolton long ago recommended, "pay for what we want and get what we pay for?"

Writing in Tablet, Tony Badran sums up the positive impact of Soleimani's disappearance from the scene:

"At one stroke, the U.S. president has decapitated the Iranian regime's chief terror arm and its most prominent extension in Iraq, where the U.S. Embassy was set on fire last week. Strategically, the killing of Osama bin Laden and, more recently, of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, pale by comparison. In addition to being responsible for killing hundreds of U.S. soldiers during the Iraq War, Soleimani directed a larger state project, which has shaped the geopolitics of the region."

Badran is right in his assessment, but his concerns relate simply to the geopolitical aspects of the assassination and its aftermath. No one seems to be talking about the religious implications, which may in the end outweigh everything else.

The Islamic Republic of Iran was brought into being largely through the inspirations of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as set down in his short treatise Hukumat-e Eslami ("Islamic Government") in 1977 and in its central doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih ("Guardianship of the Jurist"), which placed responsibility for leadership of the state in the hands of the clerical establishment. For more than forty years, the clergy have steered the Iranian ship of state through all manner of vicissitudes, keeping control of affairs through the use of sheer force and legislation based on Islamic law.[1]

What typifies Iranian Islam more than anything is that the vast majority of its people are Shi'i Muslims and that Shi'is are also the majority (64%) of Muslims in neighboring Iraq.

There is no room here for a full discussion of how Shi'ism developed in history or of how it developed in great distinction from mainstream Sunni Islam. The Shi'is have always been a minority within the Islamic world as a whole, with a belief system that differs in significant features from their Sunni rivals.

For most of their history, the Shi'a have been persecuted, something that has encouraged them to practise taqiyya, or dissimulation, in matters of faith. The main group of Shi'is, the Ithna' 'Ashariyya (Twelvers), follow the teachings and example of twelve holy imams, starting with 'Ali, who married the prophet Muhammad's daughter. When the second of 'Ali's two sons, Husayn, was killed during the Battle of Karbala in 680, his death gave rise to a cult of martyrdom that permeates the religion. The imams are regarded as manifestations of divinity on earth, and the twelfth and last imam, the Imam Mahdi, still lives in a heavenly realm from which he is destined to return to wage the last jihad in which unbelievers are finally destroyed. Messianic claims have led to violence by the Shi'a in the past, notably through the mid-nineteenth century heretical Babi movement.

For most Iranians, being proud Persians conflates with being devoted Shi'is; it is out of that conflation that the Islamic Revolution in Iran gained its strength and continues to retain control over the nation. More recently, that combination of belief and nationalism has led to increased involvement in territories from Yemen to Lebanon, beyond Iran's own borders.

Every month of Muharram, millions of Shi'a take to the streets in commemoration of Husayn's death. Men flog themselves and use knives to cut their heads, sending blood streaming down their faces. There is lamentation, sermonizing, and a range of passion plays for most of the month.

This celebration of violence is also a celebration of Husayn's bravery in rising up with an army against the then Sunni caliph, Yazid. The sense of a persecuted people rising against their oppressors may still invigorate many Shi'is, as in attacks on Saudi Arabia, or the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), although both in 2009 and more recently, protests have been against their own Iranian leaders.

Soleimani's name is already being written on posters in religious not military terms, not as "General" but as "Martyr and Pilgrim" (Shahid va Haj).

Some historians believe that we are not dealing with rational people here, yet despite the possible preference of some of the mullahs for "the end of days" and martyrdom, many others seem to prefer retaining power.

Meanwhile, Esmail Ghaani, Soleimani's successor as head of the Quds Force, has promised: "to continue martyr Soleimani's path with the same force and the only compensation for us would be to remove America from the region."

Some pundits have claimed that Soleimani's death will lead to World War III. In reality, any all-out war will end in the rapid defeat of Iran, if only because of the gross disparity between their respective military forces, with America vastly better armed.

Nevertheless, the tactics and forms of attack already in use by the Quds Force, the Keta'ib Hezbollah, and other Iranian terrorist operations abroad are likely to persist and be multiplied -- unless stopped.

Denis MacEoin is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute. He authored the standard account of Iran's militant sectarian movement, Babism, in The Messiah of Shiraz (2008).

[1] The best summary of modern Iran remains that of Michael Axworthy, Revolutionary Iran: A History of the Islamic Republic, 2nd. London, 2019.