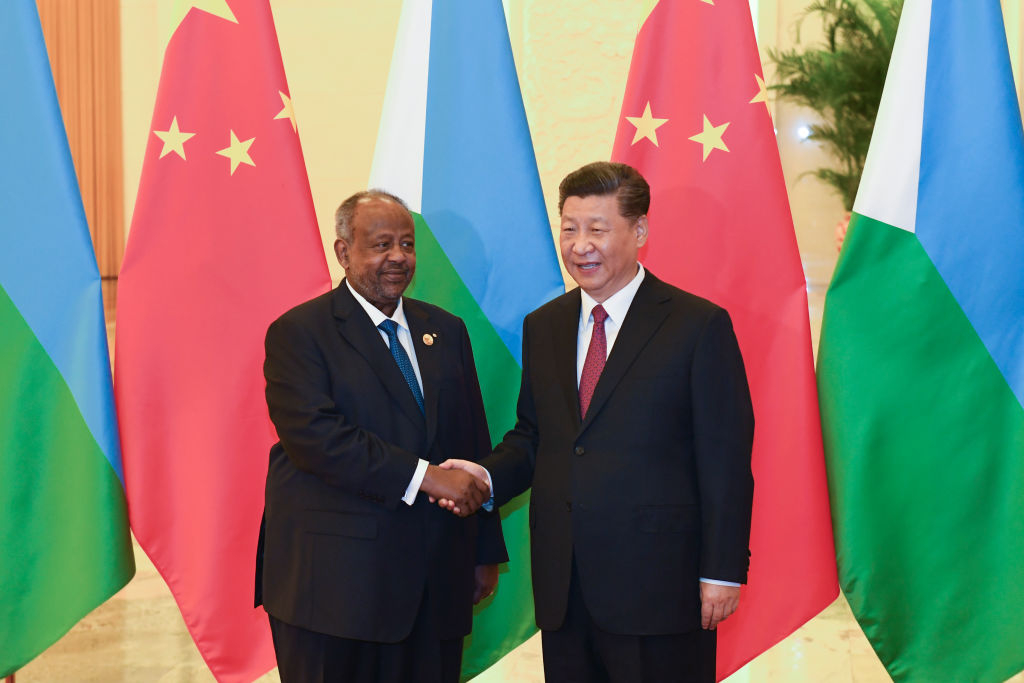

An important part of China's projected hegemonic plan is the establishment of a naval facility at the Strait of Bab al-Mandeb in Djibouti, a potential maritime chokepoint across from the Arabian Peninsula at the mouth of the Red Sea. Pictured: China's President Xi Jinping (right) meets with Djibouti's President Ismail Omar Guelleh on April 28, 2019 in Beijing, China. (Photo by Madoka Ikegami-Pool/Getty Images) |

The recent signing of the first stage of a trade pact between the United States and China should not mask what appear to be Beijing's ultimate hegemonic ambitions.

Phase 1 of the deal, which went into effect on January 19, includes a partial reduction of current -- and cancellation of planned -- tariffs; a Chinese pledge to increase American agricultural imports; and an agreement from Beijing to address Washington's concerns about U.S. technology being transferred to China by American companies doing business there, and about intellectual property theft.

While the trade deal appears to be beneficial to U.S. interests, there are two things to consider. The first is that it is likely to be temporary. The second is that it does not prevent China from its pursuing its aggressive designs on the South and East China Seas, where it is positioning itself to challenge the U.S.'s role as protector of the world's sea lines of communication (SLOCS).

Beijing's posture has both commercial and military dimensions, as its current development of a major blue-water navy illustrates. To establish and maintain such a powerful maritime force, China will need sustained deployments of its fleets, which will require a network of airfields and seaports.

In order to gain access to deep-water harbors and land for the construction of airfields, China ensnares poverty-stricken countries through a carrot-and-stick process, called a debt-trap. At the moment, "seven countries... whose external loan debt to China surpasses 25 percent of their GDP" are severely in debt to China. The "trap" involves Chinese banks lending enormous amounts of capital to governments with a poor record of development to carry out projects; when those projects fail, Beijing demands territory, national assets or access to harbors in the debtor countries. The Chinese government then dispatches teams of technicians and other workers there to build the infrastructure needed to support China's aspirations. The above scenario is playing out in places such as Sri Lanka and Cambodia.

In Sri Lanka, China's Communication and Construction Company has taken over the failed Hambantota Port and Industrial Zone development project. The corrupt former Sri Lankan president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, received huge Chinese loans to develop a port in his family's home region of Hambantota -- a project that his business advisers had deemed risky. Rajapaksa also solicited funds from Chinese banks, which he plowed into his election campaign for a second presidential term. Rajapaksa's personal indebtedness to China increased Beijing's influence on the internal affairs of Sri Lanka.

In Cambodia's southwestern coast jungle region of Dara Sakor, China is investing more than $3 billion to construct an airport and seaport for military purposes. Cambodia's concession to China includes a 99-year lease for 20% of its coastline. This arrangement provides China with the ability to keep Vietnam's granting of access to the U.S. Navy in check. It also likely constitutes a message to Hanoi and other Southeast Asian capitals, which are allied with the U.S. and opposed to China's efforts to control the South China Sea, that Beijing will not remain passive in the region.

Of equal, if not greater, significance is China's purchase of territory overlooking the potential chokepoint of the Panama Canal Zone (PCZ). A regime-affiliated Chinese company, "The Landbridge Group", in May 2017, paid Panama $900 million to control Margarita Island's port facilities. Margarita Island hosts Panama's largest port overseeing the passage of goods transported from the PCZ to the Atlantic Ocean.

Another important puzzle piece in China's projected hegemonic plan is the establishment of a naval facility at another potential maritime chokepoint, the Strait of Bab al-Mandeb in Djibouti, across from the Arabian Peninsula at the mouth of the Red Sea. Although Beijing claims that the purpose of this base is to facilitate China's anti-piracy operations along Africa's eastern coast, its primary purpose is likely to protect the transport of Persian Gulf oil upon which East Asia is heavily dependent. In addition, the base is situated extremely close to Camp Lemonnier, the only permanent American military base on the African continent.

Two other Chinese acquisitions -- adding to Beijing's ever-growing maritime "silk road" -- are in the most remote section of the Pacific Ocean. One is a 99-year lease of the Solomon Island of Tulagi, which has a deep-water port; the other is a 99-year lease of Australia's Port Darwin, where U.S. Marines train for six months of each year. This means that China will be able to document American military exercises and collect ship signal emissions from U.S. combatants. The Chinese military's presence at Darwin also will give Beijing access to the southernmost entry point to the South China Sea, which it now claims as part of its sovereign sphere.

China's presence in Tulagi and Darwin allow the People's Liberation Army Navy to leapfrog over China's near and far seas into the deep rear of the Indo-Pacific region, thus complicating America's and its allies' ability to monitor and confront Chinese naval operations in the event of a crisis or conflict.

This pattern of China's investments in some 20 ports around the globe should be of great concern to the Free World. Let us hope that the administration in Washington is paying close attention.

Dr. Lawrence A. Franklin was the Iran Desk Officer for Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. He also served on active duty with the U.S. Army and as a Colonel in the Air Force Reserve.