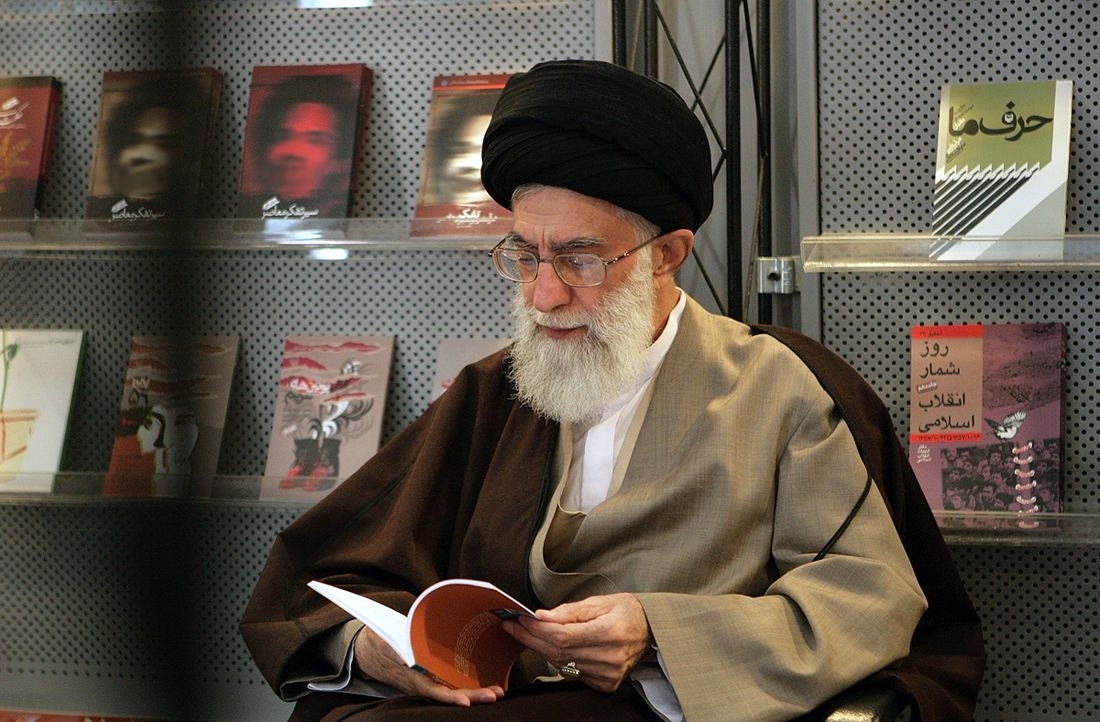

Iran's "Supreme Guide" Ali Khamenei is supposed to be excellent in everything. He has written on Islamic cuisine, the methodology of successful marriage, the destruction of Israel, the reform of human sciences, a new Islamic civilization to replace the old one that has decayed, and, as an afterthought, radical re-ordering of the global order. (Image source: khamenei.ir/Wikimedia Commons) |

In a recent speech in Tehran, Ayatollah Golpayegani, Chief of Staff of "Supreme Guide" Ali Khamenei, claimed that his boss had reached a position from which he not only led the Muslim world but also dictated to infidel powers, now in retreat.

Critics of the ayatollah might dismiss that as hyperbole beyond limits, flattery being the bane of many Middle Eastern cultures.

What if Golpayegani believes what he says?

That cannot be dismissed, especially as a chorus of flatterers isolates Khamenei from the harsh realities of life.

Self-styled philosophers claim that Khamenei is the greatest philosopher since Aristotle or, not to ruffle Muslim feathers, since Ibn Sina. Versifiers praise Khamenei as the greatest Persian poet since Sa'adi or Hafez, although only a few courtiers have heard his compositions.

The "Supreme Guide" is supposed to be excellent in everything.

He has written on Islamic cuisine, the methodology of successful marriage, the destruction of Israel, the reform of human sciences, a new Islamic civilization to replace the old one that has decayed, and, as an afterthought, radical re-ordering of the global order.

History is full of examples of leaders who, prisoners in a cocoon, dream of ruling the world.

Persian literature has many examples of dime-for-a-line poets composing panegyrics for dwarfish potentates lording it over a remote backwater but thinking of themselves as new Cyrus or Alexander.

In most cases, the leader who is isolated from reality falls victim to a political form of autism or, worse still, total alienation. Unable to maintain normal contact with society, notably by traveling and meeting different sorts of people, the alienated leader loses the sense of discernment between the real world and the imaginary universe invented by his entourage.

The late Majid Davami, one of the editors who trained me as a journalist, referred to such leaders as "emperors of a prayer rug", that is to say dictators whose real writ does not run beyond a tiny carpet even if woven of silk and gold.

Half a century later, and taking into account that we have lived in an age of inflation, I suggest we extend that metaphoric prayer rug to give the rulers in question a larger space, say one square kilometer, which is closer to reality than one might think.

Where did Abbasid Caliphs spend most of their lives, before being assassinated by Mongol bodyguards, when Baghdad was the center of the world? In a single square kilometer that is nowadays cut in half by Abu Nuwas Avenue (Shar'e Abu-Nuwas). Because things do not change as much as we think or hope, the new Iraqi ruling elite is confined to the "Green Zone" a stone's throw away.

The Akhund of Swat, the 19th century mullah who declared jihad on the British Raj in what is now Pakistan, lived in a cave surrounded by a garden, no more than one square kilometer.

More recently, we had Josef Stalin who, at the height of his power, hardly set foot out of the Kremlin and Adolf Hitler who had one square kilometer in Berlin and another in Berchtesgaden.

Rafael Trujillo, the Dominican Republic's dictator in the 1950s, decided to beautify his one-square kilometer palace-prison in Santo Domingo with a giant lighthouse that consumed half of the island's electricity. As bad luck struck, Trujillo became blind when the lighthouse was completed. So, he spent the rest of his life imagining the light that his toy shed on the Caribbean.

Haiti's dictator, François Duvalier, alias Papa-Doc, left his one-square kilometer only once, to bury his favorite dog in Port-au-Prince's central park.

Over the years, as a journalist, I met a number of one-square-kilometer "emperors" who, as the French say, belched bigger than their mouths.

Muammar Gaddafi lived in a cage in Tripoli. I was shocked to hear that he had not had time, or courage, to visit Benghazi in years.

I interviewed the Sudanese despot Jaafar Nimeiri in his "square-kilometer" universe. Pacing in his salon, waiting to be received, the curtain on one of the bay windows caught fire, causing his bodyguards to panic and run out.

Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein, too, was confined in his square-kilometer patch whenever we met before he decided to invade Iran.

As for General Muhammad Siad Barre, the Somali dictator, I am not sure that he even had a full square kilometer. I met him in Mogadishu's central barracks at 3:00 am because he feared that if he went to his palace, soldiers might stage a coup against him.

I had a surrealistic dinner with the Congolese dictator, Denis Sassou N'guesso, in his capital Brazzaville that had been turned into piles of rubble in a four-month civil war against rivals. He suggested that I visit the beauties of his city, unaware that nothing but ugliness was left.

In the 1970s, on a first visit to Beijing, I was not granted an interview with Mao Zedong because he was be "too busy".

In the 1980s, on two occasions when we met Robert Mugabe, he expressed hope to leave his square-kilometer patch in Harare, for a visit to Bulawayo that had never submitted to his domination. As far as we know, he never did.

I doubt if any of the last Soviet dictators, including Leonid Brezhnev whom we met, ever left the square-kilometer confine. Brezhnev had palaces, euphemistically called "villa" in all the capitals of the 14 Soviet republics outside Moscow. But, people told us, he had never visited any of them.

Yuri Andropov's patch was even smaller, the size of a bed, where he was attached to a dialysis machine for his kidneys.

Today, Syrian regime head Bashar Assad is confined to his square-kilometer close to Damascus with no chance of ever roaming in other parts of the war-torn country. General Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian master of PR, claims he prevented Assad from fleeing because Khamenei ordered him to stay put which, in practice, means the Syrian became a prisoner like Khamenei.

Today, Yemeni Houthis are boxed in their "empire" in the old Ottoman quarter of Sanaa.

In autobiographical notes, Khamenei waxes lyrical about the joys of visiting Shiite "holy" shrines in Iraq. Today, he dares not set foot in an Iraq shaken by uprisings against his ideology. Worse still, fearful of visiting even Mash'had, Iran's own "holy" city, he has to be content with a hussainiyah he built near a "villa" confiscated by the revolution.

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article was originally published by Asharq al-Awsat and is reprinted by kind permission of the author.