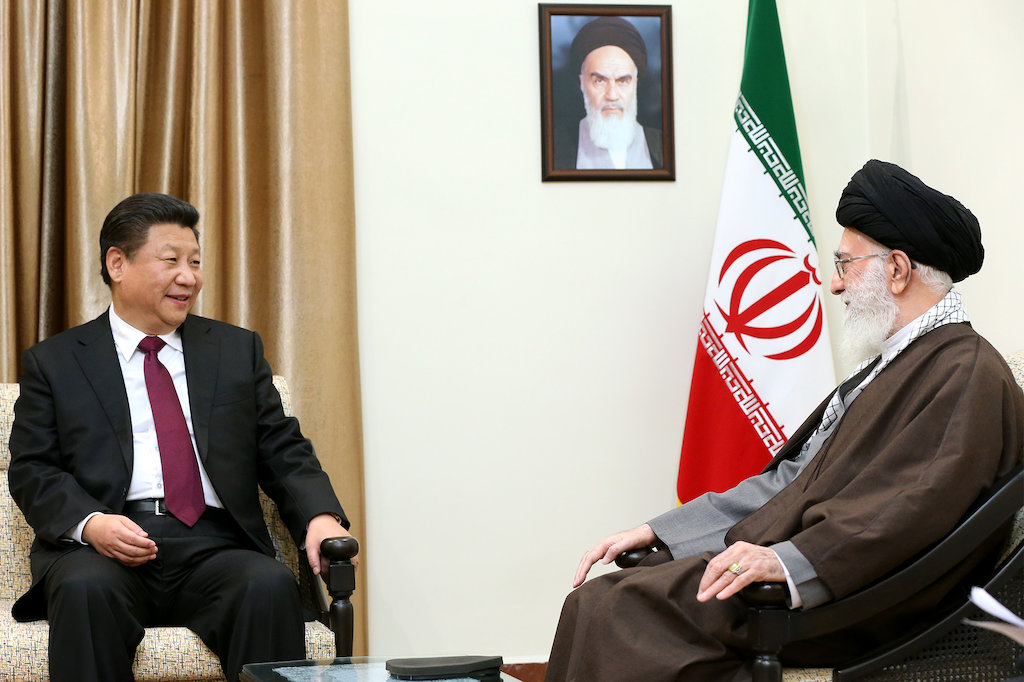

China's commitment to supporting Iran is the main reason that Arab leaders remain wary of relying too heavily on China for their future security needs. Pictured: China's President Xi Jinping meets with Iran's "Supreme Leader" Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on January 23, 2016, in Iran. (Image source: khamenei.ir) |

The confusion among Arab leaders over the Trump administration's policy towards its traditional allies in the region has opened the way for China to intensify its efforts to extend its influence in the Middle East.

In what could prove to be a serious challenge to the long-standing hegemony Washington has enjoyed in the region, Beijing is seeking to deepen its commercial ties in the Arab world, thereby encouraging Arab states to look to China to safeguard their future security needs rather than maintaining their traditional reliance on the US.

Beijing is particularly keen to stress China's high-tech capacities in areas such as its position as a global leader in building 5G telecoms networks, as well as its Belt and Road Initiative, the ambitious economic plan to build trade networks across the world which is designed to deepen commercial ties with the Middle East.

Other aspects of China's bid to expand its commercial interests in the region include Chinese-built communications networks, fast railways, state-of-the-art airports and ports costing hundreds of billions of dollars.

Many oil-rich Gulf states, such as the United Arab Emirates, have already developed close ties with Beijing, with Emirati ministers saying they are keen to advance bilateral relations with China.

US officials are concerned that other countries will follow suit as a result of continuing concerns over the Trump administration's future engagement with the region.

Previous American administrations have taken the view that maintaining close ties with pro-Western Arab states has been vital to protecting America's global interests. Since US President Donald J. Trump took office, though, Washington's dealings have been conducted on a more transactional basis, with Mr Trump's primary focus being what the US can gain from the relationship.

Concerns about the direction of American policy under Mr Trump have been heightened by Washington's contradictory approach towards Iran. On one level, the White House seems keen to maintain its punitive sanctions regime against Tehran, a move that Administration officials believe is the reason Iran's regime faced nationwide protests recently over its decision to raise fuel prices by 50 per cent.

On another level, Arab leaders have been dismayed at Washington's tepid response to recent acts of Iranian aggression in the region, such as Iran's shooting down of a US Navy drone over international waters in the summer and the carefully- orchestrated Iranian missile and drone attack on Saudi Arabia's Aramco oil facilities.

Thus, when key Arab policymakers convened in the Gulf state of Bahrain last weekend for the annual Manama Dialogue security conference, which is organised by the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, much of the discussion focused on the geopolitical struggle taking place between Beijing and Washington for influence in the region.

American officials found themselves in the unusual position of having to defend Washington's commitment to maintaining ties with the region, with John Rood, the US Undersecretary of Defence for Policy, pointing out that the US had agreed to $152 billion in arms sales to the Middle East during the past five years, as well as sending additional troops and $74 million in US spending to train 3,200 local security personnel.

Arguably, the most telling point in Washington's favour is that China remains committed to supporting Iran, a country most Arab leaders regard as being a pariah state. Beijing is committed to spending at least $250 billion in new investments in Iran, with Chinese officials blaming the rise in tensions in the Gulf on the US, following Mr Trump's decision to withdraw from the 2015 nuclear deal.

China's insistence on maintaining ties with Tehran is the main reason, though, that Arab leaders remain wary of relying too heavily on China for their future security needs.

As Saudi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Adel Jubeir said in a speech to the conference, it was important that world powers did not try to appease Tehran. "Appeasement did not work with Hitler. It will not work with the Iranian regime," he warned.

Consequently, so long as Beijing remains committed to maintaining its support for the ayatollahs, it is unlikely to prevail in its struggle to replace the US as the main powerbroker in the Middle East. The US, however, might bear in mind that "withdrawing from 'forever wars'" might be seen by adversaries of the West as an invitation to move in.

Con Coughlin is the Telegraph's Defence and Foreign Affairs Editor and a Distinguished Senior Fellow at Gatestone Institute.