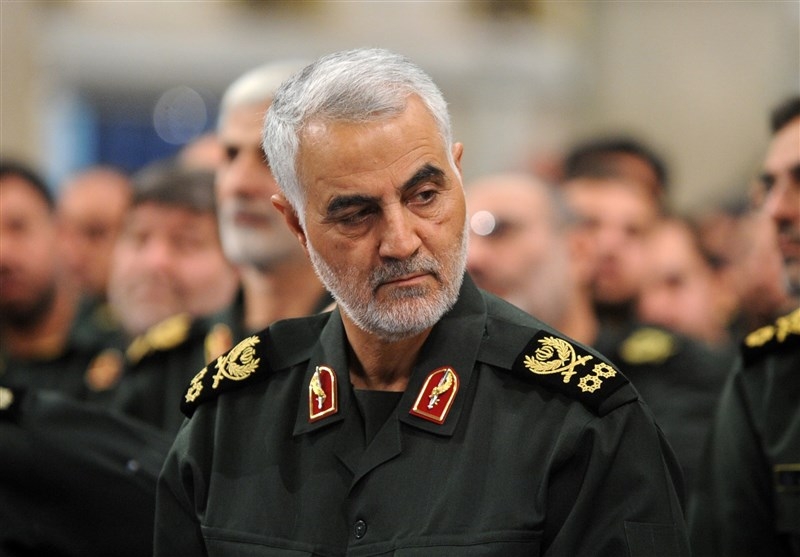

For almost two decades, Major-General Qassem Soleimani, a former bricklayer from Kirman, Iran, has been in charge of an empire-building scheme launched by the Islamic Republic. Pictured: Qassem Soleimani. (Image source: Tasnim News/CC by 4.0) |

For almost two decades, a former bricklayer from Kirman, southeast Iran, has been in charge of an empire-building scheme launched by the Islamic Republic in the early years of the new century.

The man in question is Qassem Soleimani, believed to be "Supreme Guide" Ali Khamenei's favorite military commander. One of Iran's only 13 major-generals, the highest rank in the regime's military, Soleimani has the added advantage of commanding his own military force, known as the Quds Corps, that is answerable to no one but Khamenei. In addition, when it comes to his army's budget, the general is given what comes close to a blank cheque.

According to Iran's Customs' Office, his Quds Corps also runs 12 jetties in two of Iran's major seaports for imports and exports that never feature in any official data or reports. Obtaining Iranian citizenship is one of the toughest bureaucratic ordeals in the world. Millions of Iraqi, Afghan and Azerbaijani refugees, who lived in Iran for years, were denied Iranian citizenship even for their children born in Iran. And, yet, a nod from Soleimani or one of his aides could quickly secure an Iranian passport for his Lebanese, Iraqi, Pakistani, Bahraini, Afghan and other agents and mercenaries.

According to former President Muhammad Khatami, Soleimani ran his own foreign office, appointing Islamic Republic's ambassadors to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Yemen and Afghanistan. Until recently, Soleimani could justify the investment made in his empire-building enterprise as a success. This is how Ayatollah Ali Yunesi put it: "Today, thanks to General Soleimani, we control four Arab capitals: Beirut, Damascus, Baghdad and Sanaa."

Official propaganda, ironically often echoed by Western media, portray Soleimani as a latter-day version of the men of humble origin who rose to become the Maréchal of an all-conquering France under Napoleon Bonaparte. Had he lived in Napoleon's time, Soleimani might have become king of Lebanon just as Maréchal Bernadotte who won the crown of Norway and Sweden. If the Tehran media are to be believed, Soleimani defeated the Israeli army in 2006, crushed Bashar al-Assad's opponents in Syria and dismantled ISIS's so-called "Caliphate" in Iraq and Syria while installing stable governments in Beirut, Damascus and Baghdad.

It is against such a background that the current popular uprisings in Lebanon and Iraq, not to mention the Islamic Republic's humiliating marginalization in Syria, are raising doubts about the official Soleimani narrative.

To me, at least, it is clear that Soleimani has achieved virtually nothing in Syria apart from helping prolong a tragedy that has already claimed almost a million lives and produced millions of refugees. Regardless of what denouement this tragedy might produce, future Syria will in no way reflect the fantasies of Soleimani and his master Khamenei. The general's scheme may linger on in Lebanon because his cat's-paw, known as Hezbollah, has a monopoly of arms while stealthily purging the national army of elements that might not subscribe to Khomeinist ideology. However, even then, Soleimani's militias in Lebanon are likely to be in self-preservation mode rather than acting as the vanguard of further conquests. In other words, in the medium-term, the Islamic Republic has already lost in both Lebanon and Syria.

Though they would certainly puncture the myth of Khomeinist invincibility, such losses could be absorbed because they would not directly threaten Iran's interests as a nation-state.

The case of Iraq is different.

To start with, Iraq holds Iran's longest border- 1,599 kilometers -- a fact that poses major national security concerns. Iraq is also home to the third largest community of Shiite Muslims after Iran and India. Iranian-Arab tribes have kith and kin on the other side of the border with virtually all major tribes of southern Iraq. Kurds living on both sides of the border provide an additional human bond between Iran and Iraq. The two neighbors also share huge reserves of oil, rivers and the Shatt al-Arab, a major estuary for both.

Soleimani cannot treat Iraq the way he has treated Lebanon and Syria. In Lebanon, he could appeal to sectarian sentiments by claiming that it is thanks to Tehran that Hezbollah now controls virtually all aspects of government on behalf of the country's largest religious sect.

In Syria, he could ally himself with a determined minority ready to fight the majority to the end, convinced that defeat could mean total elimination. In Iraq, however, the majority sees itself as Iran's rival for regional leadership. Even for Iraqi Shiites, it is Najaf, not Qom or Tehran, that ought to be the beating heart of the faith.

To be sure, Soleimani still controls a number of militias in Iraq, notably Asaib ahl al-Haq, the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and the remnants of the Badr Brigade. It is also no secret that numerous Iraqi politicians, and mullahs, are in Tehran's pocket. It was no accident that the other day Sheikh Qais al-Khazali simply recited an editorial from daily Kayhan, reflecting Khamenei's views, as his own analysis of the bloody events in Karbala.

Judging by noises made by Soleimani's entourage and his apologists in the official media, the general may be contemplating a Syrian solution for Iraq. If he does take that path, he would be doomed to failure. Worse still, he might create a major threat to Iran's national security as setting a neighbor's house on fire is never a risk-free enterprise.

The wisest course for Iran, even under this weird regime in Tehran, is to lower its profile in Iraq, contain its ambitions and use whatever influence it may still have to persuade the Iraqis to solve their problems within a constitutional system that has helped them come through one of the most violent phases in their nation's history. An Iraq where gunmen in Soleimani's pay paste portraits of Khomeini and Khamenei on every wall may look good to the octogenarian mullahs still in control in Tehran. However, an Iraq where peace and stability reign without the paraphernalia of Khomeinism is better for Iran's own national security and interests.

Once again, what looks good for the mullahs may be deadly for Iran as a nation.

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article was originally published by Asharq al-Awsat and is reprinted by kind permission of the author.