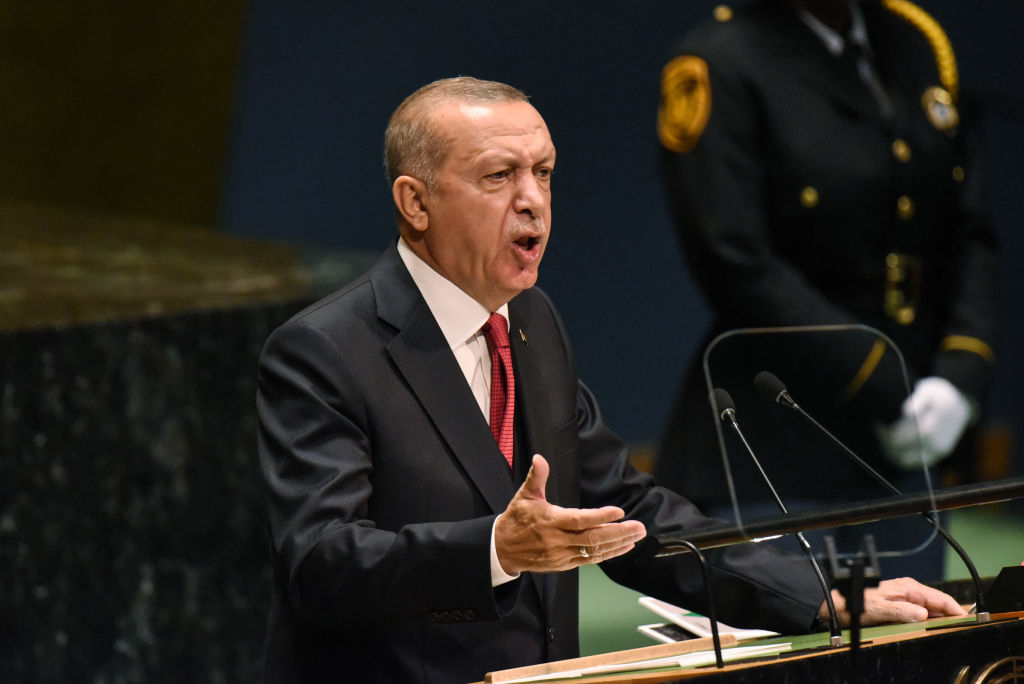

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and other members of his government have repeatedly threatened to flood Europe with migrants. On September 5, Erdoğan said that Turkey plans to repatriate one million Syrian migrants to a "safe zone" in northern Syria and threatened to reopen the route for migrants into Europe if he does not receive adequate international support for the plan: "This either happens or otherwise we will have to open the gates." Pictured: Erdoğan speaks at the UN on September 24, 2019. (Photo by Stephanie Keith/Getty Images) |

Greece has once again become "ground zero" for Europe's migration crisis. More than 40,000 migrants arrived in Greece during the first nine months of 2019, and more than half of those arrived during just the past three months, according to new data compiled by the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

The surge in migrant arrivals to Greece during the third quarter of 2019 — 5,903 arrivals in July; 9,341 in August; and 10,294 in September — has coincided with repeated threats by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and other members of his government to flood Europe with Muslim migrants.

Although the number of migrant arrivals to Greece is still far below the number of arrivals at the height of the migration crisis in 2015, when more than a million migrants from Africa, Asia and the Middle East poured into Europe, the recent surge in newcomers suggests that Erdoğan's threats to resume mass migration are becoming a reality.

In March 2016, European officials negotiated the EU-Turkey Migrant Deal, in which the EU offered Turkey a series of economic and political incentives in exchange for a pledge by Ankara to halt the flow of migrants from Turkey to Greece.

European officials, negotiating in great haste, promised Turkey more than they were able to deliver — in particular a controversial pledge to grant visa-free travel to the European Union for all of Turkey's 80 million citizens.

Since the agreement's entry into force, Turkey and the EU have accused each other of failing to honor key parts of the deal, and Erdoğan has repeatedly threatened to allow potentially millions more migrants to pour into Greece.

In practice, the EU-Turkey deal substantially reduced the flow of migrants from Turkey to Greece. As a result, migration routes shifted westward from Greece to Italy, which in 2016 replaced Greece as the main point of entry for migrants seeking to reach Europe.

After former Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini announced hardline immigration policies in June 2018, the number of arrivals to Italy fell dramatically — from 119,369 in 2017 to 23,370 in 2018, a drop of 80%, according to the IOM.

As a result of Italy's clampdown on illegal immigration, the migration flows to Europe shifted farther westward to Spain, which in 2018 replaced Italy as Europe's main gateway for illegal migration. More than 65,000 migrants arrived in Spain during 2018, according to the IOM.

The resurgence of mass migration from Turkey to Greece, however, has reverted Greece to its previous role as the main European gateway for mass migration. Greece received twice as many migrants during the first nine months of 2019 as did Spain, according to the IOM.

Greece received more migrants — 25,538 — between July and September than in the first six months of the year combined. The migrant flows have jumped by almost 180%, from an average of 100 arrivals per day during the first half of 2019, to an average of 277 arrivals per day during the third quarter.

The Greek government has said that Erdoğan personally controls the migration flows to Greece and turns them on and off to extract more money and other political concessions from the European Union. In recent months, the Turkish government has repeatedly threatened to open the floodgates of mass migration to Greece, and, by extension, to the rest of Europe.

On February 19, Erdoğan claimed that Turkey had spent $37 billion caring for displaced Syrians since 2011, and accused the EU of not doing enough to shoulder the burden. He added that if the 3.6 million Syrians in Turkey cannot be repatriated, they will end up in Europe.

On June 22, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said that Turkey had suspended a bilateral migrant readmission agreement with Greece because Athens released eight Turkish soldiers who fled to Greece after the July 2016 failed coup in Turkey. Ankara has demanded they be extradited, but Greek courts have rejected the request. The soldiers have denied wrongdoing and say they fear for their lives.

On July 21 Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu accused European countries of leaving Turkey alone to deal with the migration issue. In comments published by the state news agency Anadolu Agency, he warned: "We are facing the biggest wave of migration in history. If we open the floodgates, no European government will be able to survive for more than six months. We advise them not to try our patience."

On July 22, Çavuşoğlu said that Turkey had suspended the EU-Turkey Migrant Deal because the EU had not approved the visa liberalization for Turkish citizens. He also linked the suspension to a July 15 decision by EU foreign ministers to halt high-level talks with Ankara as part of sanctions over Turkish oil and gas drilling off the coast of Cyprus.

On September 5, Erdoğan said that Turkey plans to repatriate one million Syrian migrants to a "safe zone" in northern Syria and threatened to reopen the route for migrants into Europe if he does not receive adequate international support for the plan. "This either happens or otherwise we will have to open the gates," Erdogan said.

On September 8, Erdoğan threatened to flood the European Union with 5.5 million Syrian refugees unless he received international support for the establishment of a "safe zone" in northern Syria. "If they do not give us the necessary support in this struggle, then we will not be able to stop the 3.5 million refugees from Syria and another two million people who will reach our borders from Idlib," Erdogan told a rally in Malatya, Turkey's Eastern Anatolia region.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis called on Turkey to stop "bullying" Greece. "Mr. Erdoğan must understand that he cannot threaten Greece and Europe in an attempt to secure more resources to handle the refugee issue," he said. "Europe has given a lot of money, six billion euros in recent years, within the framework of an agreement between Europe and Turkey and which was mutually beneficial."

Erdoğan, however, appears to have the upper hand in this dispute. On August 29, for instance, 16 boats carrying a total of 650 migrants reached the Greek village of Skala Sykamineas on the island of Lesvos, according to the non-profit group, Aegean Boat Report. All of the boats were new and arrived at the same location within less than an hour, which suggests that the mass influx was a coordinated operation by people-smuggling gangs, presumably with the tacit approval of the Turkish government. It was the largest mass arrival of migrants arriving at Lesvos from the Turkish coast since the migration crisis in 2015-2016.

The mass arrivals to Greece have continued unabated: 2,441 migrants arrived during the first week of September; 1,781 arrived during the second week; 2,609 arrived during the third week; and 3,463 arrived during the fourth week.

"We are seeing huge waves being brought in by traffickers using new methods and better and faster boats," Greece's Civil Protection Minister, Michalis Chrysochoidis, said. "If the situation were to continue we would have a repeat of 2015. We are going to take measures to protect our borders and we are going to be much stricter, much faster in applying them."

On September 30, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced a series of measures to deal with the migration flows. He said that his government wants to return 10,000 migrants to Turkey by the end of 2020. The plan presupposes that Turkey will take them back. Mitsotakis also said that the government will tighten border controls, increase naval patrols in the Aegean, close centers for migrants who are refused asylum, and overhaul the asylum system.

Migrants using people-smuggling routes that originate in Turkey are also reaching other EU member states, including Bulgaria, Italy and Cyprus, which experienced a 700% increase in migrant arrivals during the first nine months of 2019, compared to the same period in 2018, according to the IOM.

Cypriot Interior Minister Constantinos Petrides said that the surge in migrant arrivals from Turkey was linked to tensions between Ankara and Nicosia over Turkey's drilling for offshore oil and gas in the economic zone of Cyprus.

Most of the migrants arriving in Cyprus do so by land. Petrides explained that Turkey has visa-free agreements with numerous countries in Africa and Asia, and that many migrants are able to enter mainland Turkey without restrictions. From there, they travel, often with the help of people-smugglers, by air or by sea, to Turkish-occupied Northern Cyprus. They are then bussed to the UN Green Line and illegally cross over into the Republic of Cyprus, the Greek-speaking southern part of the island which is an EU member state.

Speaking to reporters in Brussels, Petrides elaborated:

"The newest trend is even more alarming. It's the arrival of third-country nationals, who fly directly from Turkey by plane to the occupied airport of Timvu [its Greek name] or Ercan [as it is known today in Turkish], and then they enter the government-controlled area on foot.

"This new method of sending refugees by planes and buses could not be carried out without at least the tolerance of the Turkish authorities. And it's not just tolerance. I mentioned the practices regarding the visa-free regime, regarding these policies which encourage this phenomenon to happen. It's very clear that here we have an institutional kind of smuggling."

More than six million migrants are believed to be waiting in countries around the Mediterranean to cross into Europe, according to a classified German government report leaked to the newspaper Bild. The report said that one million people are waiting in Libya; another million are waiting in Egypt; 720,000 in Jordan; 430,000 in Algeria; 160,000 in Tunisia; and 50,000 in Morocco. More than three million others are waiting in Turkey.

Soeren Kern is a Senior Fellow at the New York-based Gatestone Institute.