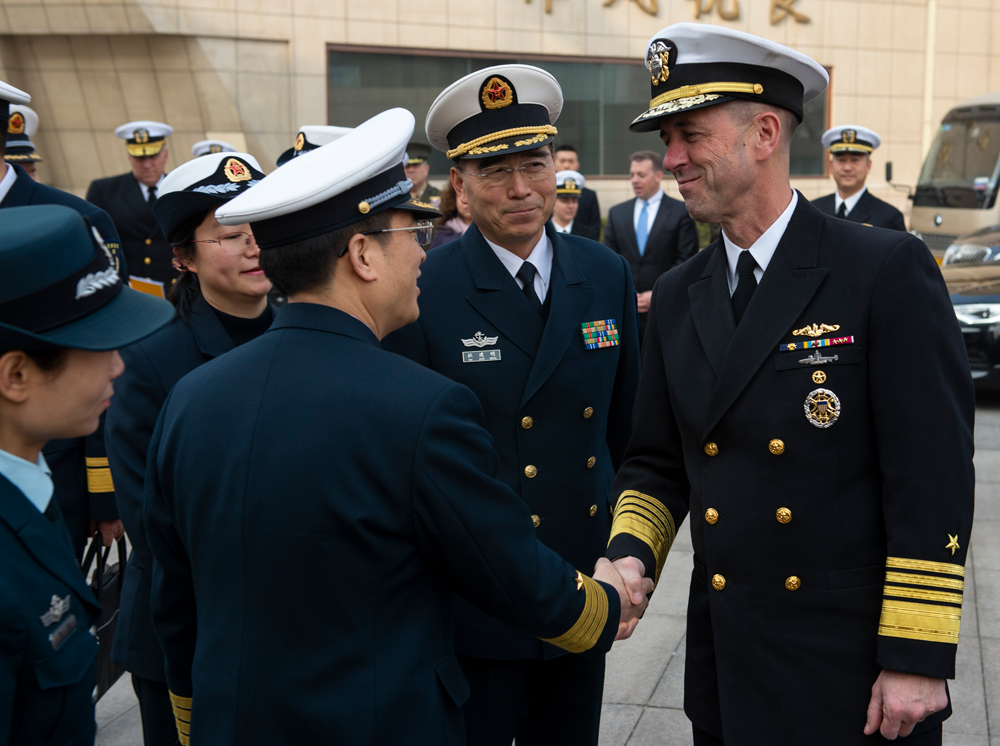

The sharp downturn in ties between the world's two most fearsome militaries was evident when America's highest naval officer, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, went to Beijing this month. Pictured: Admiral Richardson (right) is greeted by senior Chinese defense officials at the People's Liberation Army Naval Research Academy in Beijing, on January 14, 2019 (U.S. Navy photo) |

The sharp downturn in ties between the world's two most fearsome militaries was evident when America's highest naval officer, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, went to Beijing this month.

Chinese officers were ready for Richardson: they issued hostile words, especially about U.S. relations with Taiwan. In response, CNO Richardson stuck to Washington's decades-old script of cooperation.

It is time for American policymakers to change that script by, among other things, dropping themes of engagement, introducing notions of reciprocity, and showing resolve of their own.

Richardson struck an upbeat note as he left China on his second official visit as America's top admiral. "I very much appreciate the hospitality I received in China," he tweeted on January 16. "I had some great discussions with my counterparts and I look forward to strengthening our relationship as we move forward."

The admiral's words were in sharp contrast to those of the Chinese counterparts. They threatened military action against the United States. Moreover, Global Times, the tabloid controlled by the Communist Party's People's Daily, in an editorial, made veiled threats directed at Richardson. "Beijing needs to take practical action to help the U.S. correct its vision," the paper noted, after referring to military action to enforce Beijing's expansive territorial claims. "China must have the ability to make rivals pay unbearable costs."

The mismatch in the tone of the American and Chinese messaging suggest that something might possibly be wrong.

For a start, something definitely seems wrong at the top of the People's Liberation Army. Twice last month, senior Chinese officers publicly urged unprovoked attacks on the U.S. Navy. In the second of the outbursts, on January 20, Rear Admiral Luo Yuan said he wanted to use Dong Feng-21D and Dong Feng-26 ballistic missiles to sink two aircraft carriers and create 10,000 American "casualties."

Although these bellicose statements do not represent official policy, they can nonetheless be seen as reflecting thinking in senior officer ranks. In any event, they should be deeply troubling.

The proper American response was not Richardson's "I look forward to continuing our dialog as we seek common ground and opportunities for cooperation." Richardson's response should have been, "I am cancelling my trip to China."

Richardson, prior to the China trip, defended his visit:

"A routine exchange of views is essential, especially in times of friction, in order to reduce risk and avoid miscalculation. Honest and frank dialogue can improve the relationship in constructive ways, help explore areas where we share common interests, and reduce risk while we work through our differences."

"Common interests"? We hear not only unacceptably belligerent words from Luo and others; we have been seeing, and still see, dangerous Chinese actions in the global commons.

On September 30, the Lanzhou, a Chinese destroyer, came within 45 yards of the USS Decatur as it crossed the bow of the American warship near Gaven Reef in the South China Sea. The Decatur had to swerve to avoid a collision. The U.S. Navy diplomatically called the Lanzhou's maneuverings "unsafe and unprofessional."

Despite the risky conduct — and despite Beijing's denial of a requested Hong Kong port call for the USS Wasp for October — the U.S. Navy sought permission for the Ronald Reagan Strike Group to pay a port call in Hong Kong, a special administrative region of People's Republic of China, just weeks after the Decatur-Lanzhou incident.

James Fanell, a leading commentator on U.S. Navy interactions with China, told Gatestone that the port-call request undermined President Trump's tougher policy line:

"What seems clear is that the PRC has successfully convinced generations of Pentagon leaders that 'mil-to-mil' relations are important for promoting security, despite the overwhelming empirical evidence proving otherwise."

Fanell, who as a captain served as the chief intelligence officer for the Pacific Fleet, is correct about the evidence. Over time, the Chinese military has conducted a series of dangerous intercepts of the U.S. Navy and Air Force on and over the South China Sea and East China Sea.

Admiral Richardson is apparently worried about a lack of communication. Communication is not the problem. The problem is that Chinese generals and admirals have been and continue to be hostile, belligerent, and bellicose.

Moreover, no amount of talking is going to make these flag officers less so. In fact, American efforts at dialogue are making matters worse. U.S. Navy admirals may think they are acting responsibly and constructively, but the Chinese are obviously perceiving weakness and acting accordingly. The most likely explanation for Luo's comments last month is that he thought America can be intimidated into leaving the region.

General Li Zuocheng, a member of the Communist Party's Central Military Commission, also attempted intimidation. He told Richardson in Beijing that the People's Liberation Army would bear "any cost" to prevent foreign interference in Taiwan matters.

After leaving China, Richardson, to his great credit, suggested sending a carrier strike group through the Taiwan Strait. "We don't really see any kind of limitation on whatever type of ship could pass through those waters," he told reporters in Tokyo.

The next step for the U.S. is to drive a carrier through the Strait, as the Navy last did in 2007 after the Chinese denied a port call in Hong Kong.

Why stop with just one carrier strike group? Arthur Waldron of the University of Pennsylvania told Gatestone that, to make a lasting impression on Beijing, the U.S. should arrange a Taiwan Strait passage with not only the supercarrier Ronald Reagan but also a flotilla of "some Japanese subs and the Izumo; any British, French, or Australian ships available; and the Taiwan navy shadowing it." He also recommends sending along planes to add to the effect.

"We do not want war," Waldron wrote in a message to defense professionals last week. "This is how you prevent it. Remember, show overwhelming power not indecision or weakness. Some Chinese will read the smoke signals correctly."

The best way to avoid conflict in the Taiwan Strait, as Waldron suggests, is to make it clear to Beijing that America will defend Taiwan. In the last two months, Beijing has been making threats to invade. Unfortunately, as Joseph Bosco, a former China desk officer in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, points out, the best Washington can do at the moment is issue "mushy diplomatese" that the Chinese can interpret as a lack of American resolve.

"You can bet," Bosco told Gatestone last week, "China's calculations would change dramatically if President Trump or Secretary Pompeo or the new SecDef or John Bolton were to utter these words publicly to Beijing: 'We will defend Taiwan under any circumstances.'" That would, he said, "effectively reconstitute the 1954 U.S.-Taiwan mutual defense treaty" and "alter the strategic dynamic in Washington's and Taipei's favor."

Some — actually a lot — of "altering" is absolutely necessary, and now is not a moment too soon. In the first half of 2012, the U.S., despite firm obligations to defend the Philippines, did nothing when China took over Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea. When Chinese generals and admirals saw Washington's failure to act, they turned the heat on other Philippine reefs and islets, went after Japan's islands in the East China Sea, and began reclaiming and militarizing features in the Spratly Islands chain. Feebleness only emboldens Chinese aggression.

There will be no good endings in Asia until Washington disabuses Beijing of the arrogant belief that it can take whatever it demands.

How to do that? Perhaps, in addition to sailing through the Taiwan Strait, Admiral Richardson can arrange for a few U.S. Navy vessels to make a port call on the island and linger for a while.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China and a Gatestone Institute Distinguished Senior Fellow.