On New Year's Eve in Manchester, England, a 25-year-old man began stabbing people at random on a platform at the city's Victoria Station, while reportedly shouting ISIS slogans. Pictured: Victoria Station in Manchester. (Image source: Mike Peel/Wikimedia Commons) |

An enormous amount about the hopes and expectations of a society can be learned from the news that people want to report and the stories its readers apparently want to hear. An equally large amount -- perhaps even more -- can be learned from the stories they would most likely rather not hear and the facts they would probably prefer not to know about.

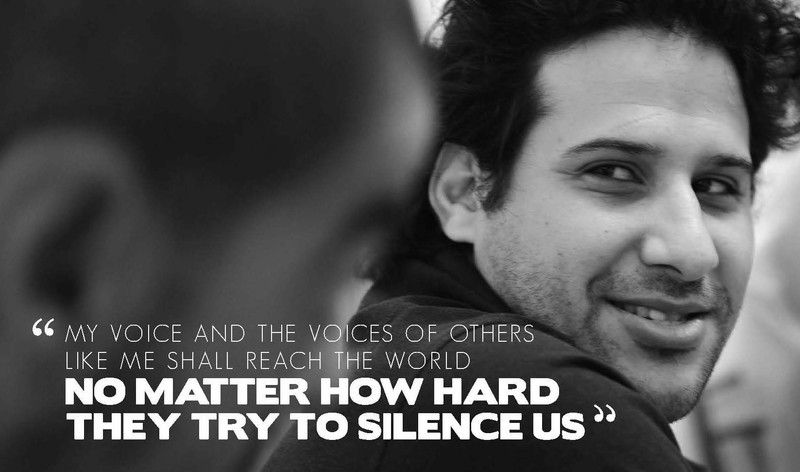

The former situation can be seen after any Islamist terrorist attack in the West, when people are immediately given 'good news stories' either to dampen any rage they might be feeling or distract from any difficult questions they might be asking. On New Year's Eve in Manchester, England, for instance, a 25-year-old man began stabbing people at random on a platform at the city's Victoria Metrolink station. It appears that the venue was chosen because it is near the Manchester Arena, where Salman Abedi murdered 22 people in a suicide-bombing at a pop concert in May 2017.

Before a nearby police officer and his colleagues could stop him, the New Year's Eve attacker left a couple in their 50s seriously injured in what was described as a 'frenzied' attack. He has subsequently been detained under the Mental Health Act. What seemed clear from the outset, however, was that the attack was in some way Islamist, specifically ISIS-inspired. The man was reportedly shouting ISIS slogans during the attack; and footage of him after he was detained by police show him shouting 'Allahu Akbar' ['Allah is the greatest'].

Lest it be forgotten, it was three years ago, after a terror simulation in the city (in order to prepare emergency services for what turned out to be an imminent scenario) that the heads of the Greater Manchester police evidently felt impelled publicly to apologise for an actor in that 'rehearsal' shouting 'Allahu Akbar'. Muslim groups and others argued then that having such a scenario was 'Islamophobic'.

In any event, in the aftermath of the New Year's Eve attack, there were prime examples of searches for 'good news stories'. These swiftly landed on a woman in a headscarf who was among the passersby to assist the couple who had just been attacked. 'The angel of Manchester' some papers said. Across social media various campaigners insisted that this kindness -- rather than the attacker -- was 'the true face of Islam'. Like anyone else who stops to help strangers, the woman obviously deserves considerable praise. There is, though -- in this search for the good story among the bad -- something desperate and self-deluding.

By contrast, consider the stories that are not popular to report and events on which most of the media would seemingly rather not focus. Earlier this month, just such a story emerged from Golders Green. For decades, this area of London has been associated with Britain's Jewish population. Because of their high number in the area, there was some concern in 2017 when a Shia Muslim group bought the huge Golders Green Hippodrome for £5.25 million to establish a large mosque. The possible significance of this purchase was dampened down by Jewish community leaders, who criticised those concerned about the mosque's arrival.

To their credit, the leadership of the mosque, since it opened, have been making efforts to reach out to, and reassure, the local Jewish population. Inevitably, there has been much talk of inter-faith initiatives and inter-faith dialogue. Events at the start of this month, however, point to one of the present futilities around these means of communal reassurance.

As part of their efforts to reassure local Jews of their good nature, the Golders Green mosque had planned to show an exhibition which would highlight the role that some Muslim Albanians played in helping to protect some of their Jewish neighbours during the Holocaust. Britain and Albania are, of course, are a continent apart. It is also probably safe to say that Albanian affairs, even extremely recent ones, are rarely a priority for residents of the UK. Obviously, the twin purpose of such an exhibition would simply be to show Muslims that there were heroic Muslims in the past -- as today -- who are willing to make a stand against the worst inhumanity, and also to remind Jews that, as well as there being people from the Muslim community who have always had a deadly intent towards their people, there have also been others who have been allies and friends. It is hard to see who could object to such a message.

Except, of course, that there are. Among the Islamist-oriented groups in Britain is one revolving around a website called '5 Pillars'. Its editor, Roshan Salih, also works for the Iranian state broadcaster Press TV, which had its broadcasting license in the UK removed after it showed forced confessions of prisoners inside Iranian jails in the wake of the uprising crushed by the Iranian government in 2009. Since news of the exhibition emerged, Salih has led a campaign to boycott it. The reason he and '5 Pillars' claim as their excuse is that the Holocaust exhibit is coming from Yad Vashem, and Yad Vashem is Israeli. Those -- including Muslims -- who have criticised the exhibition's critics have been dismissed by Salih as simply 'Zionists'.

Now the exhibition has been scrapped.

There are the usual saving-something-from-the-rubble noises from communal leaders about the need to 'continue working together'. But little will actually be learned. For the same reason that there has been little focus -- outside of the Jewish community press in Britain -- on this whole story. The reason is obvious.

Perhaps the mosque leadership in Golders Green are good. Perhaps they were motivated by more than short-term fence-building in deciding to hold an exhibition about the Holocaust. The question to ask is why are there so many people in the Muslim community who would object to such an exhibition and why these extremists have so much sway (as opposed merely to being an embittered fringe) that they can actually get their way. If a church in Britain put on an exhibition about the Holocaust, it would not be forced to cancel it under pressure from any Holocaust-denying Anglicans. Far from it. If such an unlikely event were to occur, the entire direction of the ire would be towards anyone trying to stop such an event. The exhibition would go ahead without anyone flinching. So what is it about the fragility, and vulnerability of the Muslim community to the dictates of extremists that we can learn from an episode such as this one?

Quite a lot, I would suggest. Which is one of the reasons why there has been so little focus. Because what can be learned from such events are lessons that, as a society, we still seem distinctly unwilling to learn.

Douglas Murray, British author, commentator and public affairs analyst, is based in London, England. His latest book, an international best-seller, is "The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam."