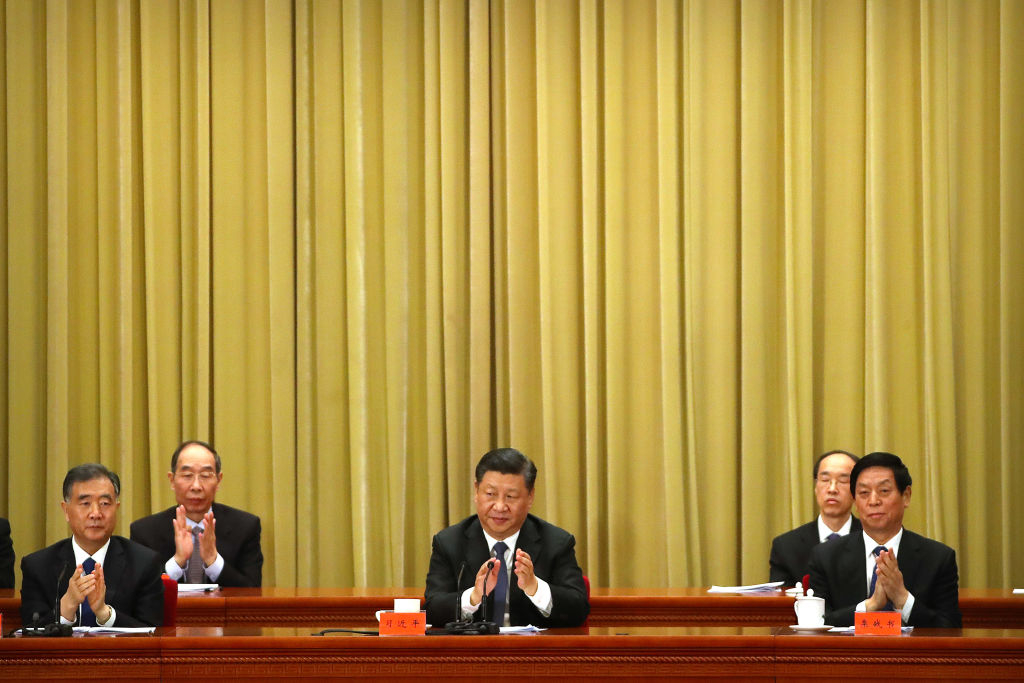

The trend of Chinese ruler Xi Jinping's recent comments warns us that his China does not want to live within the current Westphalian system of nation states or even to adjust it. From every indication, Xi is thinking of overthrowing it altogether. Pictured: Xi Jinping (center) at a Chinese Communist Party event on January 2, 2019 in Beijing. (Photo by Mark Schiefelbein-Pool/Getty Images) |

"I hear prominent Americans, disappointed that China has not become a democracy, claiming that China poses a threat to the American way of life," Jimmy Carter wrote on the last day of 2018 in a Washington Post op-ed. That claim, Carter tells us, is a "dangerous notion."

There is nothing more dangerous than a notion from the 39th president, even on China. China, despite what he said, threatens not only America's way of life but also the existence of the American republic. Chinese ruler Xi Jinping has, in recent years, been making the extraordinary case that the U.S. is not a sovereign state.

The breathtaking position puts China's aggressive actions into a far more ominous context.

Carter, and almost all others who comment on Chinese foreign policy, see Beijing competing for influence in the current international order. That existing order, accepted virtually everywhere, is based on the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, which recognizes the sovereignty of individual states that are supposed to refrain from interfering in each other's internal affairs. Those states now compete and cooperate in a framework, largely developed after World War II, of treaties, conventions, covenants, and norms.

Many Chinese policymakers believe they are entitled to dominate others, especially peoples on their periphery. That concept underpinned the imperial tributary system in which states near and far were supposed to acknowledge Chinese rule. Although there is no "cultural DNA" that forces today's communist leaders to view the world as emperors did long ago, the tributary system nonetheless presents, as Stephen Platt of the University of Massachusetts points out, "a tempting model" of "a nostalgic 'half-idealized, half-mythologized past.' "

In that past, there were no fixed national boundaries. There was even no concept of "China." There was, as Yi-Zheng Lian wrote in the New York Times, "a sovereignty system with the emperor's compound in the middle." Around that were concentric rings. "The further from the center, the less the center's control and one's obligations to it," Lian noted. The Chinese, in fact, were perhaps the first to develop the idea of a borderless world.

In short, Chinese emperors claimed they had the Mandate of Heaven over tianxia, or "All Under Heaven," as they believed they were, in the words of Fei-Ling Wang of Georgia Tech, "predestined and compelled to order and rule the entire world that is known and reachable, in reality or in pretension." As acclaimed journalist Howard French writes in Everything Under the Heavens, "One can argue that there has never been a more universal conception of rule."

Unfortunately, the current Chinese leader harbors ambitions of imposing the tianxia model on others. As Charles Horner of the Hudson Institute told me, "The Communist Party of China remains committed to ordering the People's Republic of China as a one-party dictatorship, and that is perforce its starting point for thinking about ordering the world." In other words, a dictatorial state naturally thinks about the world in dictatorial terms. Tianxia is by its nature a top-down, dictatorial system.

Xi Jinping has employed tianxia language for more than a decade, but recently his references have become unmistakable. "The Chinese have always held that the world is united and all under heaven are one family," he declared in his 2017 New Year's Message. He recycled tianxia themes in his 2018 New Year's message and hinted at them in his most recent one as well.

Xi has also used Chinese officials to explain the breathtaking scope of his revolutionary message. Foreign Minister Wang Yi, in Study Times, the Central Party School newspaper, in September 2017 wrote that Xi Jinping's "thought on diplomacy"—a "thought" in Communist Party lingo is an important body of ideological work—"has made innovations on and transcended the traditional Western theories of international relations for the past 300 years." Wang with his time reference is almost certainly pointing to the Westphalian system of sovereign states. His use of "transcended," consequently, hints that Xi wants a world without sovereign states—or at least no more of them than China.

The trend of Xi's recent comments warns us that his China does not want to live within the current Westphalian system or even to adjust it. From every indication, Xi is thinking of overthrowing it altogether, trying to replace Westphalia's cacophony with tianxia's orderliness.

Xi not only spouts tianxia-like statements, his regime also employs scholars to study the application of tianxia to the world.

He also acts tianxia. His China in December 2016 seized a U.S. Navy drone in international water in the South China Sea. Chinese spokesman Yang Yujun said, according to the official Xinhua News Agency, that one of its navy's lifeboats "located an unidentified device" and retrieved it "to prevent the device from causing harm to the safety of navigation and personnel of passing vessels."

In fact, China's ships had over a long period tailed the USNS Bowditch, an unarmed U.S. Navy reconnaissance vessel. The American crew, who at the time were trying to retrieve the drone, repeatedly radioed the Chinese sailors, who ignored their calls and, within 500 yards of the U.S. craft, went into the water in a small boat to seize it. The Chinese by radio told the Bowditch they were keeping the drone.

The site of the seizure, about 50 nautical miles northwest of Subic Bay, was so close to the shoreline of the Philippines that it was beyond China's expansive "nine-dash line" claim. There was absolutely no justification for the Chinese navy to grab the drone. The intentional taking of what the Defense Department termed a "sovereign immune vessel" of the United States showed that Beijing thought it was not bound by any rules of conduct.

Beijing now thinks it can, with impunity, injure Americans. In the first week of May, the Pentagon said that China, from its base in Djibouti, lasered a C-130 military cargo plane, causing eye injuries to two American pilots.

The laser attack in the Horn of Africa, far from any Chinese boundaries, highlights Beijing's unstated position that the U.S. military has no right to operate anywhere and that China is free to do whatever it wants anyplace it chooses. And let us understand the severity of the Chinese act: an attempt to blind pilots is akin to an attempt to bring down their planes and an attempt to bring down planes is an assertion China has the right to kill.

China has been called a "trivial state," one which seeks nothing more than "perpetuation of the regime itself and the protection of the county's territorial integrity." This view fundamentally underestimates the nature of the Chinese challenge. China, under Xi Jinping, has become a revolutionary regime that seeks not only to dominate others but also take away their sovereignty.

Xi at this moment cannot compel others to accept his audacious vision of a China-centric world, but he has put the world on notice.

These events together mean, once again, that Carter has failed to understand a hardline regime. In his op-ed, he warns America against starting "a modern Cold War" with China. Washington, in reality, cannot start anything. There already is a struggle that Xi Jinping has made existential.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China and a Gatestone Institute Distinguished Senior Fellow.