The two key words in assessing the President's nominee to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy are stare decisis. This ancient Latin phrase, which means let the decision stand, represents a conservative approach to judging: that precedent imposes constraints on judicial innovation. Put another way, that judicial innovation should be balanced against the need to maintain stability in our legal system. But like most legal terms, stare decisis can easily be manipulated to benefit both conservatives and liberals. Traditionally it has been conservatives who have embraced stare decisis, allowing the dead hand of the law to constrain the living constitution. But liberals, too, embrace the concept when they seek to preserve old precedents that are important to them.

Today, liberals want to use stare decisis to preserve Roe v. Wade, gay marriage and other iconic liberal decisions of the past. Many conservatives would like to see these decision overruled. When the President interviews potential nominees, and when the Senate advises and consents on the nomination, these nominees will be questioned about their positions on important cases of the past and their likely votes in the future. They will decline to be specific claiming the need for judicial independence. But one area of legitimate inquiry will be their institutional views regarding stare decisis.

All judicial nominees, whether liberal ore conservative, will always throw a bone to stare decisis. They will claim, quite correctly, their legal system depends on stability, certainty and predictability. But they will also point out that the law must sometimes change to suit the times. So the questioning of these potential nominees must be more probing and substantive. They should be asked about the criteria they apply in determining whether to be bound by past decisions.

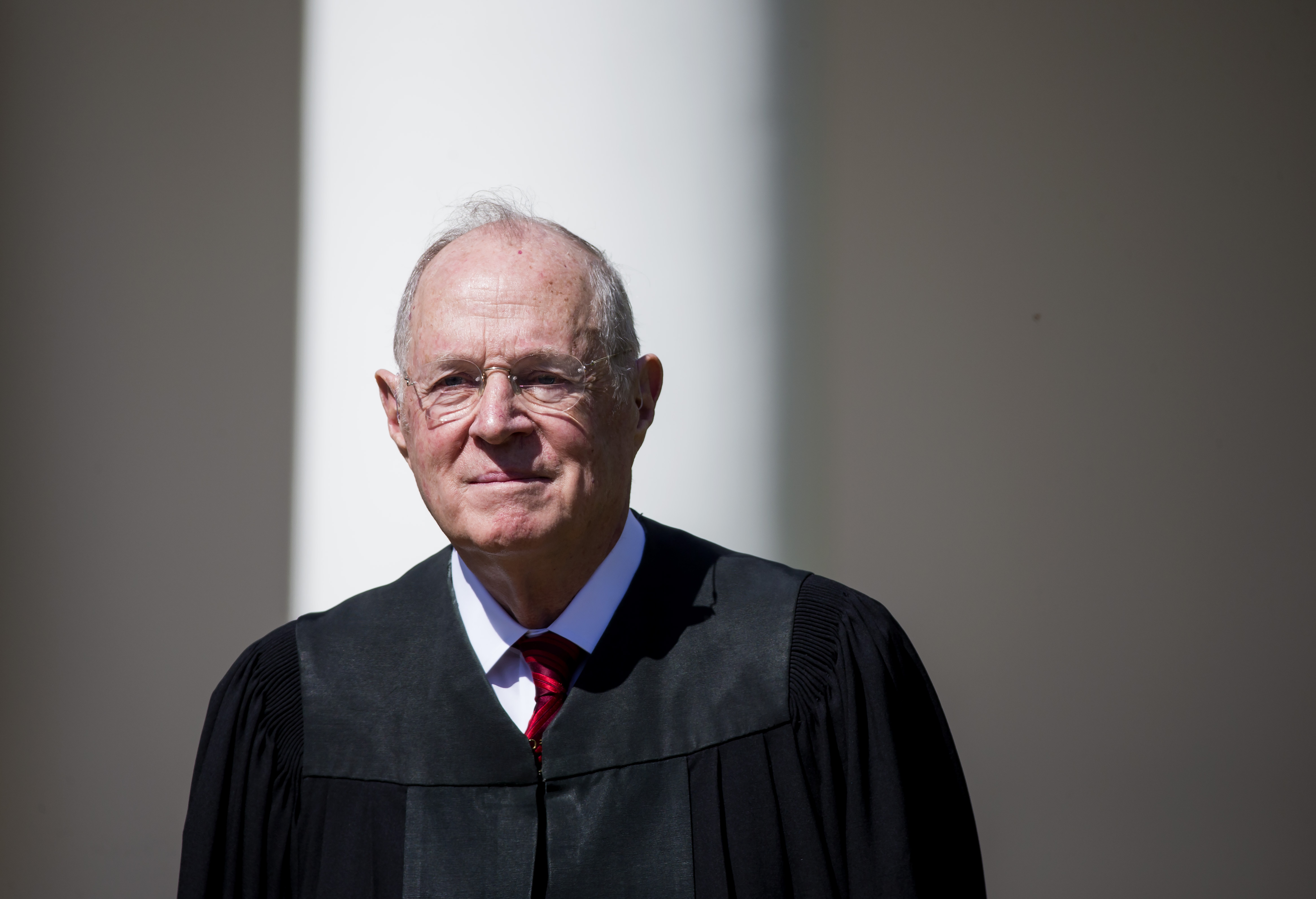

Justice Anthony Kennedy. Among the key issues that may influence President Trump's decision on whom to nominate to replace the retired judge will be the candidate's view on Roe v. Wade. (Photo: Eric Thayer/Getty Images) |

The Supreme Court, unlike the lower courts, is not technically bound by stare decisis. As the late Justice Antonin Scalia frequently pointed out, his oath of office required him to apply the Constitution, not the decisions of his predecessors on the bench, if those past decisions were wrong.

Just this week liberals applauded when the Supreme Court finally and decisively overruled the disgraceful Japanese-American cases of the 1940s. Conservatives applauded when the Supreme Court overruled the old compulsory dues for public union's case and ruled that public employees could not be required to pay union dues if they object to the union's political positions.

Every justice through history has applied stare decisis in many cases and refused to apply it in some. For some justices, it is difficult to discern a coherent pattern. They apply precedent when it serves their interests, and refuse to apply it without articulating why they have done so, in some cases and not in others.

Among the key issues that may influence President Trump's decision on whom to nominate will be the candidates' view on Roe v. Wade. These views can fall into several categories: the first is that Roe v. Wade was wrong when decided, it is wrong now, and it should be overruled. President Trump has suggested that he expects his nominee to take that position, but any such nominee may have difficulty being confirmed, because at least two Republican Senators opposed reversing Roe v. Wade.

The second position is that Roe v. Wade was wrong when decided but it has been the law for 45 years, and the nation has come to rely on it as governing law. Accordingly, it should not be overruled, but nor should it be expanded. This is the most likely position that a successful nominee might take.

Then there is the extreme position, hinted at by Justice Clarence Thomas: Not only is there no right for a woman to have an abortion, but it is unconstitutional for the state to allow abortion, since abortion violates the right to life of the fetus. Such a radical view would dramatically change both constitutional law and politics in America, but the Supreme Court's decision interpreting the second amendment granting the personal right to own guns also reversed long standing precedents and changed the nature of law and politics in our country. It is unlikely that any nominee with such an extreme view concerning abortion could be confirmed, if he or she acknowledged that they would vote to prevent states from keeping abortion legal.

So the next several months may be a civics lesson for all Americans as we observe the President making his decision about whom to nominate and we watch Senators make their decision as to whether they confirm the nominee. We need such a lesson because the vacancy that occurred when Justice Scalia died provided an object lesson in politics trumping decency and constitutionality, as Senate Republicans violated their duty to advise and consent, by refusing even to consider any nominee put forward by President Obama in his last year. Let us hope that the process of replacing Justice Anthony Kennedy will provide a more ennobling lesson for all Americans.

Alan M. Dershowitz is the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law Emeritus at Harvard Law School and author of "The Case Against BDS."