As Ramadan drew to a close this year, the spectacle of a contrived Muslim rage on the last Friday of Islam's sacred month -- branded "Al- Qud's [Jerusalem] Day" by Iran's late leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – was on display across the Muslim world and in the West.

The Qur'an, Islam's sacred text, calls upon Muslims to fast during Ramadan as part of prayers and quiet reflection "to ward off evil." Extremist Muslims, instead, call upon their co-religionists to display their rage against their real and imagined enemies, especially Jews. Most Muslims, however, steer away from such angry demonstrations, which degrade the meaning and purpose of their devotion to fasting and prayers during the month in which the Qur'an was first revealed to Muhammad.

The public display of rage on the last Friday of Ramadan, which has now become a ritual since Khomeini called for it soon after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, is another vivid indicator of how deeply and fatefully divided within itself is the Muslim world.

The causes dividing the Muslim world are many, given the vast diversity among Muslims of ethnicity, language, culture, resources, levels of literacy and economic development. Public display of rage increasingly seems an indicator of the collective frustration of many Muslims in their inability to understand and contend with the requirements of the modern world.

The late scholar Bernard Lewis devoted his 1990 Jefferson Lecture -- later published as "The Roots of Muslim Rage" in the Atlantic Monthly -- in explaining how to make sense of "Muslim rage."

The Nobel laureate in literature, V.S. Naipaul, after witnessing regular displays of this rage across the Muslim world during his travels, observed in his book, Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey, that it was as if "the Muslim world had been on the boil."

This pervasiveness of Muslim rage, frequently accompanied by violence, might be explained as a symptom of pre-modern cultures caught in a whirlpool of a much-delayed transition into modernity. Muslims, in effect, are trapped in a state of bewilderment over how to repair their broken cultures, or how to build them anew -- when they are full of doubts about what is new, what is modern and what has been built by others belonging to a different faith and culture. If they need to build what is new to them, they require reconciling modernity with the principles of their own faith tradition and culture. This is the nub of their problem as Muslims -- not extremists, as extremists dogmatically insist that the solution for any and all problems of the Muslim world is the unreconstructed implementation of Islamic law, Shariah.

Analogies for understanding the problems involved in transitioning from pre-modernity to modernity exist in India, the world's largest democracy, and China, the world's fastest-growing economy, and both are two of the oldest civilizations. Yet both are still having difficulty making the passage to modernity.

Muslims in general are a "third world" people whose understanding and practice of Islam remain fixed in their pre-modern cultures. As a matter of belief, Muslims take the Qur'an as divine revelation and its meaning as eternally valid. If this belief is the doctrinal truth for Muslims, then a reading of the Qur'an in the modern age cannot be the same as it was, for instance, in the 10th century. To many Muslims, though, due to their pre-modern worldview, this paradox is mostly incomprehensible. It is also hugely obstructive in easing their transition to modernity. Neither the Indians nor the Chinese have had to overcome a similar obstruction bound up with their respective pre-modern religiously based worldviews in their effort to modernize.

Hence, Muslims need to open their minds to a new reading of the Qur'an that will be consistent with the requirements of the modern age, science and democracy. They need to rethink the relationship between God and man: embracing modernity does not mean abandoning God.

In our lifetime, Muslims have had to confront the fundamental theological questions that were once faced by Christians. Despite flaws, Christianity emerged from a long, conflict-ridden history in reconciling with modernity, represented by open societies and liberal democracies, based on the rule of law and individual freedom. To evolve theologically into present day Christianity, it underwent a tumultuous transition from a Europe of the Inquisition, complete with witch-hunts and burning heretics tied to stakes, to the Renaissance, the wars of Reformation and Counter-Reformation, Enlightenment, philosophical and scientific revolutions, revolutionary wars of dynasties and emergent states, regicides and civil wars, the guillotines of the French revolution, the Reign of Terror, colonial conquests, world wars, the Russian Revolution, genocides, fascism, gulags, and the Holocaust.

If all of the above in Europe's transition has been more or less forgotten, we need merely to observe the horrific violence within the contemporary Muslim world and recognize how much alike it is to what occurred in Christendom between the time that Christopher Columbus set sail on his voyage of discovery and when Allied forces liberated Europe from Nazi Germany.

As political questions are sometimes theological in nature, and vice versa, different cultures have had to work out answers as to what God means to them, or how people of different faith traditions apprehend God. In most societies the relevance of God is central to the meaning of a "good society" in moral and ethical terms.

In Islam, unlike in Christianity, theology as a tool of religion is an impoverished discipline. In Islam, the certainty about God's reality as the omnipotent Creator, the Lord of the Universe and the Master of the Day of Reckoning is never in question. God's reality is at once simple and overwhelming; He is singular, unique and there is none like Him.

Islam, an offspring of Abrahamic monotheism, also insists on God as One, Absolute and Transcendent. In Islam and in Judaism, there is not much to be disputed about the nature of God as there has been in Christianity. In Islam, since the early years of the religion, Muslim religious scholars have instead been preoccupied with the details of prescribing laws derived from God's revelation to Muhammad as the last prophet; in other words, to work out the details of the right way to live, derived from the ethical norms set forth in the Qur'an.

According to traditional Islam, man is God's vice-regent on earth. As God's deputy, his role is to fulfill God's command set forth in the revelation received by Muhammad. God is Sovereign; He has spoken; and a righteous Muslim is one who abides by His command, follows the traditions of the prophet, and is faithful to his community and its customs as compiled in Shariah – the legal code prepared by jurists during the first three centuries of Muslim history (the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries of the Common Era).

Traditional Islam, by and large, is preoccupied with the externalities of religion -- the observance of rituals and customs -- and the minimum requirements of faith that bind individuals into communities. Its understanding and interpretation of the Qur'an are literal. It was shaped by the thrust of history that turned it, in the years immediately following the demise of the prophet, into a world-conquering faith, which brought Arabs from deep in the desert and from the margins of civilizations to found an empire and sweep aside the armies of Byzantium and Persia.

The triumphal and unprecedented entrance of Arabs, as the first Muslims in history, was also, in retrospect, the vulnerable part of how Islam came to be understood and practiced. The certainty about God that filled the pre-modern imagination of Muslims – and which, in large measure, shaped the political culture of Islam -- left them unprepared to deal with a new world that emerged around the time of the 16th century. In addition, as their early victories receded in memory and history, defeats suffered at the hands of non-Muslims came to pose troubling questions about the nature of their religious convictions.

There was a brief flash of interest in theology during the early two centuries of Islam. This interest was awakened, in part, as a result of conquests that brought Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians in Persia and Hindus in India into the realm of Islam, causing the Arabs of the desert to come into contact with high cultures, which posed difficult and challenging questions to their simplistic faith in the God of Abraham. The Qur'an is very much a Jewish book that recalls for Muslims the story of Jews -- the people most proximate to the Arabs among whom Muhammad was born and raised -- and instructs the pagan Arabs on the worship of One God.

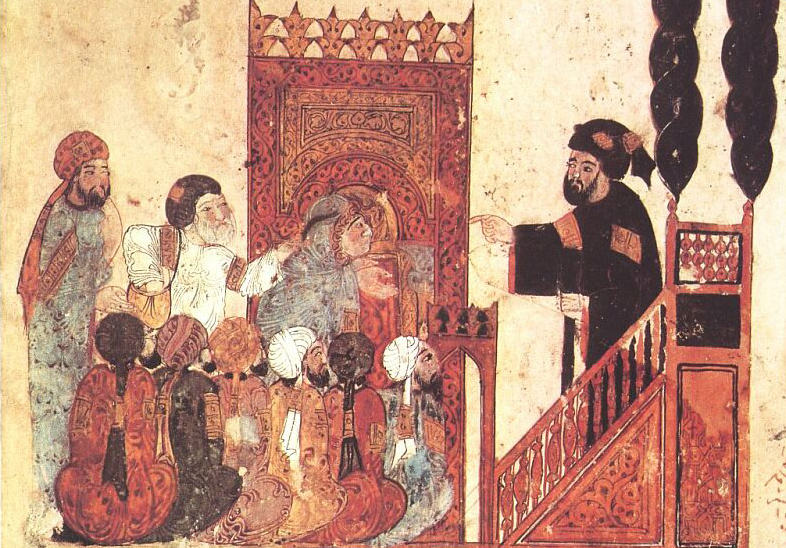

In Baghdad, the Arab capital of the Abbasid rulers as Caliphs of Islam during the early Middle Ages, inquiry and debate took place about revelation and reason. The writings of some ancient Greek philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle, were made available through the conquest of Alexandria and translated into Arabic. Curiosity was aroused. Could God be apprehended outside of revelation and, if so, would the God of the philosophers be the same as the God of revelation?

In Baghdad, the Arab capital of the Abbasid rulers as Caliphs of Islam during the early Middle Ages, inquiry and debate took place about revelation and reason. Pictured: An image from an Abbasid manuscript, produced in the year 1237. (Image source: Académie de Reims/Wikimedia Commons) |

At first, the Caliphs encouraged such speculative discussions, for it seemed that there could be nothing about them that threatened the supremacy of Islam either religiously or politically. With such encouragement, Muslim thinkers emerged to suggest that, logically, revelation and reason could not conflict: that God's creations were sustained by the laws He set for them and these laws could be apprehended by man's rational faculties. These Muslim thinkers were known as Mu'tazilites, or rationalists. They initially won the favor of the Abbasid rulers, but the traditionalists -- who preached a populist doctrine appealing to the common man's piety -- mounted effective resistance to their speculations.

Dispute was never far from the question about whose understanding of God was closest to what was revealed in the Qur'an. The rationalists tended to read and interpret the text non-literally, with a greater attention to the hidden meanings of terms expressed allegorically, and to describe God's attributes and prescriptions as universal and inclusive; their opponents, the traditionalists, insisted on the particulars, on the concrete and historically specific examples, on a literal reading of the text that laid greater insistence on God's absolute power than on the universality of His justice and mercy.

The major collision came over the issue of predestination versus free will. Had God predetermined all things, including man's conduct, for all times? Or was man a free agent whose choosing between good and evil was responsible for his conduct? This schism was further aggravated by the debate over whether the Qur'an is relative in time and should be understood accordingly -- with the prescriptive verses of the Qur'an read contextually -- or whether it is eternal and coeval with God. The opponents of the Mu'tazilites found support among common men, and their populism eventually turned the rulers against philosophers and early theologians of Islam. There was an inquisition, and the rationalists were condemned as heretics and forbidden to propagate their supposedly subversive ideas. Hence, speculative enquiry, philosophy and theology in Islam came to be proscribed and Islamic culture, as a result, soon arrived at a dead end.

There is a parallel here with nominalism in Christian thinking that came several centuries later. The most prominent Christian theologian associated with this doctrine is William of Ockham (1285-1347) in the early 14th century. Ockham sought to rebut Christian scholastics and their effort to reconcile Aristotle's rationalism with revelation. The works of those who followed St. Thomas Aquinas -- those who believed in Thomism and its goal to mediate between God and man -- appalled him.

Ockham and his followers argued, as the opponents of Mu'tazilites had done, against universals that would constrain God's unique and absolute power to create at each instant of time whatever He wishes. It was not for man, they argued, to comprehend God, who is not bound by any law, consideration, demand or supplication of His creation. In seeking to place God beyond all contingency, in making the distance between God and man as absolute as God is omnipotent, Ockham and the nominalists seemed to turn Him into a capricious sovereign, one to be feared and obeyed; one whose will must be submitted to without questioning.

Nominalism as a theological doctrine was eventually trounced as Christendom advanced by embracing rationalism. In the Muslim world, the reverse had happened. The defeat of rationalism entrenched what might be described as the Muslim version of nominalism; it suited the needs of the rulers and buttressed their tendency to reign with arbitrary power. The Muslim jurists declared about the same time that there was nothing further to add or amend to the corpus of legal rulings that they had derived from the Qur'an and the traditions of the prophet. Consequently, the doors of what is known in traditional Islam as ijtihad -- the effort invested in interpreting the sacred text -- were closed, and Muslims were required to abide by the corpus of laws formally compiled into Shariah.

The officially approved understanding of God in Islam, both in the majority Sunni tradition and in the minority Shi'ite tradition, appeared arid and unsatisfying to many Muslims. These Muslims quietly turned to mysticism, and became known as Sufis. They did not, however, openly contest the official doctrine; they publicly abided by the prescribed rituals of popular or traditional Islam.

The Sufis searched for the inner meanings of the Qur'anic verses. In their view, the outer realm of Islam hid the inner dimension of man's spiritual journey to seek a union with God. For them, God was the source and fulfilment of love; and, at times, their quest – driven by the desire to experience, in the here and now, the presence of God in their lives – was condemned by the orthodoxy as heresy.

Sufism is the humanizing of God. A verse in the Qur'an (50:16) states that God is closer to man than his jugular vein, and the Sufi is one who affirms that, apart from God, all else is unreal.

The Muslim world currently appears trapped within the parameters of the pre-modern world, based on its quasi-nominalist view of God. The Sufi understanding of God as universal love seems not fully to meet the Muslim world's urgent need to figure out how to negotiate modernity without abandoning the God of the Qur'an.

The fury of the internal upheaval inside the Muslim world -- the Muslim rage that is incomprehensible to non-Muslims -- will eventually exhaust itself when a sufficiently large segment of the Muslim population reconciles reason and revelation to discover that God never meant any religion, including Islam, to be a burden preventing man from threading a relationship with Him in harmony with human nature.

As the transition from pre-modernity to modernity proceeds with its twists and turns, the Muslim world, over time will progress and develop to the point that eventually there will arise a theology, as occurred in Christendom, consistent with the needs of Muslims and reconciled with modernity.

Salim Mansur teaches in the department of political science at Western University in London, Ontario, and is the author of "The Qur'an Problem and Islamism"; "Islam's Predicament: Perspectives of a Dissident Muslim"; and "Delectable Lie: A Liberal Repudiation of Multiculturalism."