"Consolidation". In Moscow these days this is the word that most flavors discussions in political circles. The idea is that, thanks to President Vladimir Putin's bold and risk-taking strategy, Russia has made a number of major gains on the international scene and must now act to consolidate those gains and reduce the diplomatic, economic and political price it has had to pay for them.

The analysis is inspired by Lenin's famous "Two-steps-forward, one-step back" dictum that saw the founder of the now defunct Soviet Union abandon vast territories under the Brest-Litovsk Treaty in order to consolidate the then fragile Bolshevik hold on power in Russia itself. Later, Lenin used the same dictum to justify his New Economic Policy (NEP), a step back to confuse the growing opposition from the hated "bourgeoisie".

Putin may appear an unlikely student of Leninism, having obtained his initial political education in the shadier world of the KGB under Yuri Andropov. Nevertheless, the man now cast as the unchallenged master of Russia's destiny has always shown a talent for adopting a low profile when needed.

He did that as Boris Yeltsin's right-hand-man, to the point that many regarded him as little more than a bag-carrier for the bombastic president while, all along, he was learning the ropes and preparing to ascend to the top of the greasy pole that is power in Russia.

Putin has learned another lesson from the Soviet era, this time from Andrei Gromyko, who dominated Russian foreign policy for almost half a century. Gromyko believed that the so-called Westphalian system, in place at least until the Second World War, had been replaced by a duopoly in which only the USSR and the United States counted as powers that could truly affect things.

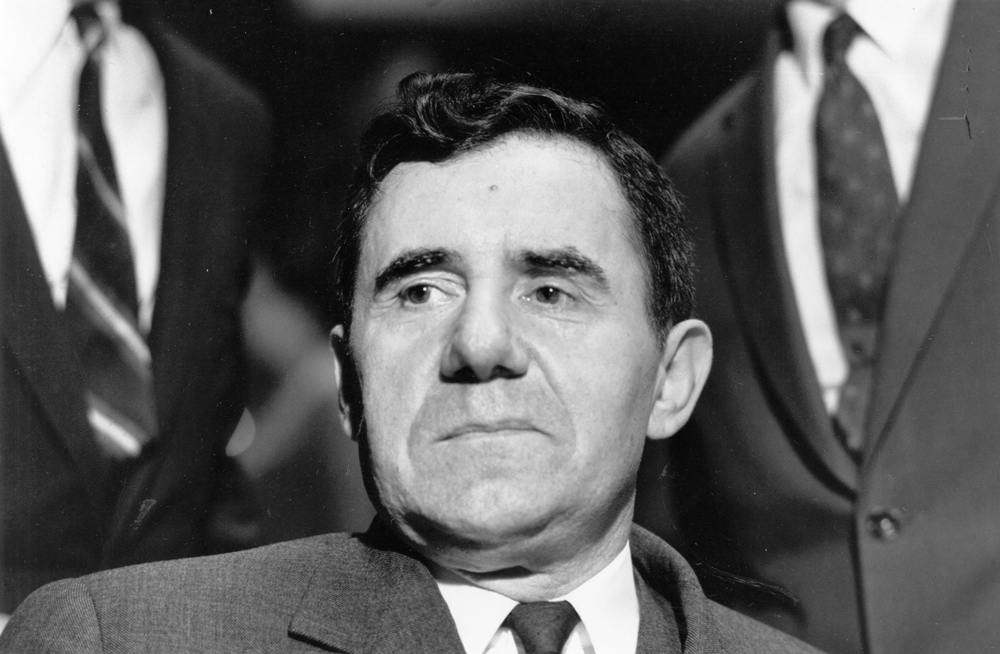

Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko at the United Nations, September 21, 1961. (Photo by William Lovelace/Express/Getty Images) |

It is no surprise that Moscow these days is full of rumors and speculation regarding an impending bid by Putin to revive at least in part and in a new form, the Gromykan "duopoly" by reaching out to the Trump administration in Washington.

Talk of a Trump-Putin summit this year intensified last week with news of a trip to Washington by Jon Huntsman, the US Ambassador to Moscow and a noted believer in rapprochement with Russia, to prepare the ground for the encounter.

Trump and Putin met twice in 2017, in Hamburg during the G-20 summit and in Vietnam when attending the Asia-Pacific leaders' gathering. According to Russian sources, although no major issue was formally discussed, the two men "felt rather good" in each other's presence.

Since then Putin has made a number of moves to please Trump and placate opponents of rapprochement with Russia in Washington.

Putin scaled down the suggested response to the US decision to close Russian consulates and trade offices and expel a large number of Moscow's diplomats.

In Syria, Putin canceled the promised delivery of S-300 anti-aircraft systems that could have made Israeli and American strikes against Iranian and Bashar al-Assad bases riskier.

More importantly, perhaps, Putin played host to Israeli Premier Benjamin Netanyahu and his Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman, who came to inform Russia of Israel's intention to force Iranian forces and their Lebanese, Afghan and Pakistani mercenaries away from areas touching on the Golan Heights and the Israeli frontier. Pressure by Putin seems to have been effective, as Tehran stopped sending new "volunteers for martyrdom" to Syria almost 8 weeks ago. In fact, recruitment of new Afghan and Pakistani mercenaries seems to have been halted altogether.

Tehran is clearly angry at what state-owned media call "the Russian betrayal."

"In December, February, April and May Israel attacked the positions of Iran and Hezbollah in Syria without the slightest barrier or difficulty," an editorial in the official agency IRNA said on May 30. "In those attacks many of our men became martyrs and many more were wounded. However, Moscow decided to ignore the aggression and kept total silence."

The editorial, clearly dictated by the leadership, also reveals that Iran had proposed to enter into a formal alliance with Russia to counter Western influence, but had met with reluctance from Moscow. Tehran wanted a "regional coalition" which would also include Iraq and Lebanon, the governments of which Iran believes it controls. Moscow was not interested.

Clearly, Putin subscribes to Gromyko's duopolistic view, according to which small players like the Islamic Republic, even if accompanied by real or imagined satellites like Lebanon and Iraq, are not worth a prayer when a deal with the US may be possible.

To make it clear that he intended to reduce Tehran's role in Syria, Putin also excluded Iran from his "consultation" with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Bashar al-Assad. More importantly, Putin has made it clear that he wants Iran to prepare for the withdrawal of all its forces, including the non-Iranian mercenaries, from Syria. Putin sent his special envoy Alexander Lavrentiev to Tehran to tell the ruling mullahs that Russia wanted both Iran and the Lebanese branch of Hezbollah out as part of a bigger plan to have all foreign forces, except Russians, out of Syria.

A day later, the Russian oil giant Lukoil announced it was putting on hold a contract to develop new Iranian oil and gas fields.

Putin knows that without reaching out to the US he may not be able to consolidate his gains in Crimea, eastern Ukraine and Georgia, while he could become stuck in the Syrian quagmire with no prospect of getting out anytime soon.

There is also the fact that weak oil prices and sanctions imposed by the US and the European Union are beginning to affect living standards across the country. At the same time, Russian oligarchs are making less money and find it more difficult to obtain Western visas and secure opportunities for putting their money in Western banks.

Russia's isolation was best illustrated during the big annual military parade in May 2017, when of all the foreign dignitaries invited by Putin only one turned up: the President of Moldova.

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article was originally published by Asharq al-Awsat and is reprinted by kind permission of the author.