Last week, two events injected energy and excitement into what was beginning to look like an anemic end of the year in the Middle East as far as political developments are concerned.

The first event was the decision by the Saudi leadership to create a new mechanism to deal with alleged cases of corruption, embezzlement and influence-peddling.

The sheer number of cases referred to a special court on those charges was enough to capture the headlines. The fact that the 208 people under investigation included princes, prominent bureaucrats, and business tycoons intensified the event's headline-grabbing potential.

But what really attracted world attention was the unexpectedness of the Saudi move.

Few, even among genuine or self-styled experts on Saudi Arabia, expected Riyadh to go right to the heart of the matter rather than dance around the issues as had been the norm in the past. Some observers, including many in Western think-tanks, warned of the danger of instability inherent in departure from old patterns of behavior.

However, the latest move is in accordance with the kingdom's new strategy aimed at recruiting the concept of change as an ally rather than a threat.

It is possible to argue that because old methods didn't produce the desired results, stability, which had been a key asset of the kingdom for decades, had morphed into stagnation. Thus, the new strategy is designed to end stagnation and prepare the path for a new form of stability capable of reflecting changed social, economic and political circumstances of the kingdom.

If Saudi Arabia is genuine in its declared desire to become an active member of the global system, the first thing it has to do is to offer the rule of law in the sense understood by most people around the world.

Trying to build an economy beyond oil, Saudi Arabia needs to attract massive foreign investment in both financial and technological domains. And that won't be possible without a strong legal system backed by transparency, competition and equality of opportunities.

And that means putting an end to influence-peddling, fake credit-lines secured by pressuring local banks, the grabbing of public land, "sweetheart" agency deals, kickbacks, baksheesh and, in short, the medieval wasitah culture.

The dramatic round up of "the usual suspects" shows that the new leadership in Riyadh is ready to cut the Gordian Knot with a hard blow.

As for Lebanon, a similar method has been used.

Prime Minister Saad Hariri's resignation ends the "grin-and-bear it" tradition in the face of intolerable situations. Under that method, Middle Eastern leaders brush the dirt under fine carpets, including at times that, as was the case with Hariri, they have responsibility without power.

Regardless of how Hariri's resignation came about, it has dramatically highlighted the fact that the "deal" made over Lebanon in October 2016 has failed.

Under that "deal", the Islamic Republic of Iran, operating through its Hezbollah network in Beirut, secured the presidency for General Michel Aoun in exchange for Hariri returning as Prime Minister.

Soon, however, it became clear that while Aoun and Hariri respectively played the roles of President and Prime Minister, real decisions were taken in Tehran. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani made that point clear in a speech in Tehran, when he said that "nothing is done" in a number of Arab states, notably Lebanon, without Iran's approval.

Hariri's dramatic departure shows that "this kind of Lebanon" doesn't work.

The current line-up under which a foreign power controls the country through one part of one community among all Lebanese communities is fundamentally flawed and dangerous in the medium and long terms.

Lebanon's raison d'etre, and the principal factor in its survival and partial success as a state, has been its system of power-sharing based on respect for diversity. Whenever one community or a combination of communities tried to exercise exclusive power, the country was plunged into turmoil.

In the 1950s, the Maronite community tried a power-grab, which led to inter-communal conflict and foreign military intervention. In the following decade, a similar bid was made by pan-Arab elements backed by Nasserist Egypt, again producing conflict and foreign meddling.

The 1975-90 Civil War also had its genesis in foreign intervention, through rival local sectarian proxy groups.

In part of that period, Aoun tried to switch Lebanon to the side of Saddam Hussein in Iraq while, backed by Iran, Hafez al-Assad threw Syria's weight behind the rival camp.

Between 1984 and 1990, Aoun wore many hats as Prime Minister, Defense Minister, Foreign Minister, Information Minister and military junta chief, often all at the same time. When we first met him in Paris in October 1990, his main message was "saving Lebanon from Syria and Iran."

Aoun's analysis would have been appreciated if he had talked of "saving Lebanon from domination by any foreign power."

There are some nations whose chief vocation is to be neutral, acting as buffers among rival power blocs. Switzerland was allowed to form and mature as a safe haven for rival European powers often at war against one another.

Afghanistan was created as a buffer between the Tsarist, British and Persian Empires in Asia. In post-colonial Indochina, the kingdom of Laos played that role until the US sucked it into the Vietnam War as collateral damage. In Latin America, that role has been assigned to Uruguay, and in Central America to Costa Rica.

During the Second World War, neutral Sweden provided a channel of communication between the United States and Nazi Germany and a safe haven for people fleeing from the Nazis and the Soviets.

After World War II, by being declared neutral, Austria played a crucial role in the repatriation and/or transfer of millions of refugees across war-shattered Europe.

By turning Lebanon into one of its bunkers, Iran has done a great disservice to the whole region, not to mention the damage done and could still do to Lebanon.

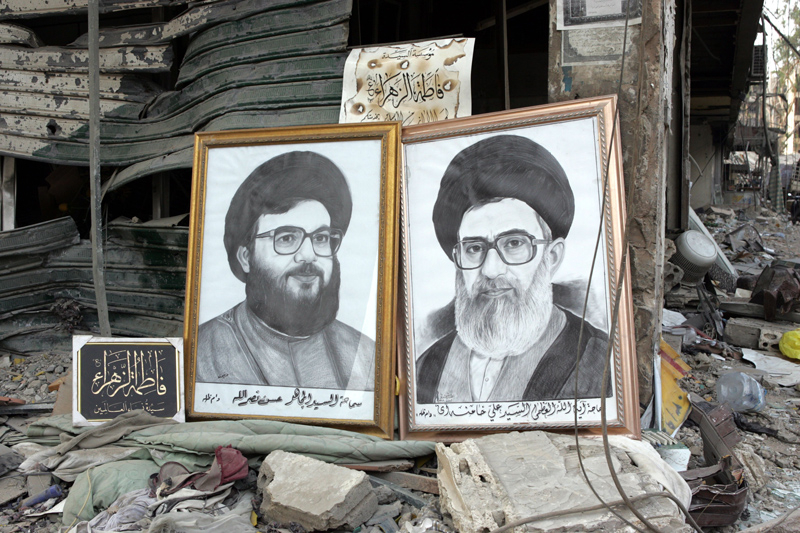

Pictured: Portraits of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah (left) and Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (right) in Beirut, Lebanon, in 2006. (Photo by Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images) |

Hariri's resignation could prove useful by posing a crucial question: Should Lebanon re-become Lebanon or should it be a glacis for the Islamic Republic in its quest for an unattainable regional hegemony? Part of the answer, of course, depends on the Lebanese themselves. They should decide whether or not they want to have two governments, one visible the other semi-visible, two armies, and a master puppeteer laughing at them in Tehran.

A Lebanon run from Tehran through Hezbollah gunmen is unlikely to attract the investment, trade, tourism and cultural exchanges that it needs to function as a modern dynamic society.

When Iran itself is denied all those things, how could it provide them for Lebanon? Iranian intervention that contributed to turning Iraq, Syria and Yemen into battlefields could do the same to Lebanon.

Amir Taheri, formerly editor of Iran's premier newspaper, Kayhan, before the Iranian revolution of 1979, is a prominent author based on Europe. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article first appeared in Asharq Al Awsat and is reprinted here with the kind permission of the author.