When in a recent column we speculated that the China is preparing to reveal its ambitions for global leadership we didn't expect this to happen so soon. Yet, this week Chinese President Xi Jinping informed the 19th Congress of the ruling Communist Party that the People's Republic was now ready to seek a more active presence in the international arena.

Three factors may have contributed to Xi's decision to bring forward his world leadership bid.

The first concerns Xi's desire to, ever so gingerly, build up his own status within the Chinese political system. He wants to be something more than his predecessors Hu Jintao, Hu Yaobang, Li Xiannian and Hua Guofeng were. Xi's ambition is to surpass even Deng Xiaoping, the "strongman" who, many believe, made the new China possible. President Xi may not be able to aspire to the status that Mao Zedong, the father of the People's Republic, attained; but he sure wants to get as near to it as possible.

Putting the Leader above the melee is of crucial importance in a system based on highly centralized command and control.

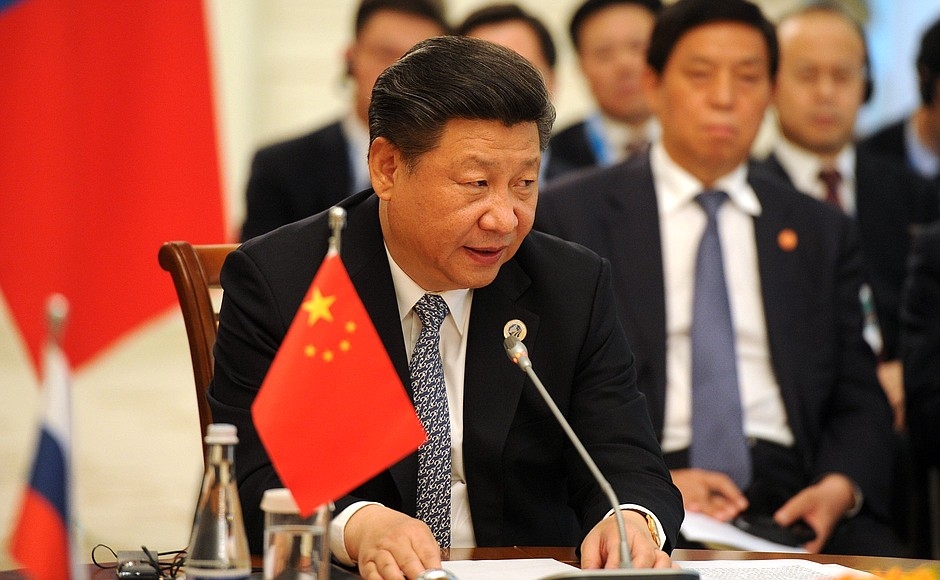

China's President Xi Jinping. (Image source: Kremlin.ru) |

After Mao's death, Hua Guofeng, though a decent leader, never managed to get above the melee.

That enabled Deng Xiaoping, who had emerged from banishment during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, to make an unexpected comeback and seize control of the levers of power by relying on the military. And while Deng was alive it mattered little who played the role of the President of the People's Republic.

After Deng's death, none of those who assumed the presidency managed to raise their status above the party factions.

Because the top layer of China's ruling elite consists of a few hundred families with revolutionary credentials, the system they run requires a father figure who has the final word on all key issues. After Deng's death "the revolutionary families" agreed on a formula under which each generation holds power for 10 years and then bows out of the stage. The rotation formula allowed more people to nurture ambitions while waiting their turn to exercise power.

For the first time, Xi now feels that he can assume the role of father figure with no clear limit to his tenure. This was highlighted when the Congress decided that Xi's "thoughts and teachings" should become integral parts of the Chinese Communist Party's charter a doctrine, a rare distinction. Before Xi, Mao Zedong had received such a distinction in his lifetime and Deng Xiaoping after his death.

More importantly, perhaps, he also believes that such a role is vital for the preservation of the current power structures.

This is why Xi speaks not only of the next five years that, under the old formula, remains of his tenure, but spells out his vision for decades to come. Such a vision, he believes, provides the stability and certainty that China needs to project its new power in the global arena.

The second factor that Xi has in mind is the need to revisit the Communist Party's narrative. Between 1949, when Mao seized power, and the 1970s, when it had become clear that Maoism was a failure, a narrative based on class struggle and the fight against imperialism, effacing the "humiliation" inflicted by Western powers, was used to give party rule some legitimacy.

With Deng's reforms, the narrative changed into one of improving the material conditions of the masses. There is no doubt that, on that account, China has been a spectacular success.

The slogan "Increase the Gross Domestic Product" has become a reality as China has experienced an incredibly high growth rate for almost two decades. With an annual GDP of around $12 trillion, China is now the world's largest economy after the United States and expected to bypass the US by 2023.

The modernization of China's infrastructure, or in many cases lack of it, is truly phenomenal. Right now, China has the world's fastest trains and is building 80 new airports. More importantly, at least a third of the population, some 400 million, has been pulled out of abject poverty for the first time since time began.

China's economic miracle, though impressive, isn't unique. France achieved its "miracle" under the mild authoritarian rule of Napoleon III. Newly-created Germany did the same under the "Iron Chancellor" Bismarck.

The authoritarian Meiji era chaperoned Japan into the modern world. Stalin, Mussolini, and even the Kim dynasty in North Korea have shown that by mobilizing resources, no matter how meager, for specific results, an authoritarian regime can achieve its lofty goals.

However, rapid economic growth, as other authoritarian regimes have found, has its downside in the form of an emerging middle class which soon demands political liberties and the gangrene of corruption that might run out of control.

Thus, Xi feels that the Communist Party can no longer justify its monopoly on power with sole reference to economic success.

So, what better than claiming a global leadership role to flatter the Chinese masses and persuade them to steer clear of politics and enjoy the fruits of their economic success?

Interestingly, President Xi told the Congress that China could promote its "model of governance" as an alternative to Western democracy. A majority of ruling elites in the world today would be more comfortable with the "Chinese model" of central control than the American model of perpetual infighting and cultural-political civil war.

The third factor that Xi has in mind is the growing vacuum left by the United States' inability or unwillingness to play its traditional world leadership role in the past decade or so.

Under President Barack Obama, who believed that America had not always been a force for good on the global stage, the US was put in a strategic retreat mode. Under President Donald Trump the same retreat has continued under the new "America First" slogan.

Filling the vacuum thus created isn't easy. The European Union is beset by its own internal contradictions, highlighted by Britain's Brexit.

Russia would love to see itself in the driving seat but lacks the economic power and the cultural dominance to make much headway beyond its nearby environs.

All that provides China with an opportunity that President Xi seems determined not to miss.

However, global leadership isn't just a matter of aspiration. It requires cultural charisma, soft power, scientific and technological innovation, and networks of social and political contacts across the world, and a solid military machine with a global reach, all things that China may not be able to offer. Nevertheless, President Xi has declared his nation's ambition. So watch this space!

Amir Taheri, formerly editor of Iran's premier newspaper, Kayhan, before the Iranian revolution of 1979, is a prominent author based on Europe. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article first appeared in Asharq Al Awsat and is reprinted here with the kind permission of the author.