It is a testimony to the peculiarities of international attention to world events that while every tweet by US President Donald Trump triggers an avalanche of reports, analyses, and outright abuse, little attention is paid as the People's Republic of China prepares to hold its five-yearly National Congress of the Communist Party in Beijing.

And, yet, China is now established as the world's largest economy in gross domestic product (GDP) terms and the second-biggest exporter after Germany. It also has the world's fastest-growing portfolio of foreign investments with interests in 118 nations across the globe.

At the same time, at least 10 million Chinese are working abroad, almost always on projects sponsored by Beijing, helping transform large chunks of Africa, South America, and Asia.

According to estimates, there are already more than three million Chinese in Siberia, spearheading a 19th-century-style campaign to exploit the region's vast natural resources. First encouraged by Moscow, the Chinese presence has become a source of concern for the Kremlin which fears losing control of Siberia due to demographic imbalance. This is why Russia now offers free land and seed capital to any Russian citizen who wishes to settle in Siberia. (Few have taken the offer, so far!)

China has launched projects that recall the golden days of European imperial expansion in the 19th century. The new Silk Road project, the biggest in human history by way of the $1.4 trillion investments, will link the Central Asian heartland to the Indian Ocean via Pakistan, directly or indirectly affecting the economies of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Russia, India, Pakistan, and Iran. A direct rail link, already been tested between Beijing and London, is to be extended to other major European capitals.

China is also studying the building of a Central American railroad as an alternative to the Panama Canal, which is incapable of receiving ships with extra-large containers.

In Africa, China has not only established itself as the biggest trading partner but is also emerging as the "wise old aunt" who could bash heads together and persuade local rivals not to upset the apple cart.

In sub-Saharan Africa, China has replaced the United States, not to mention the old colonial powers such as France and Britain, as the principal influence-wielding big power.

On a broader scale, the spectacle of President Trump and his Secretary of State Rex Tillerson begging China to "do something" about North Korea's provocative behavior is a good indicator of Beijing's growing influence.

Even in the so-called Shanghai Group, a Chinese initiative, it is now Russia that is asserting itself as the ringleader with the backing of former Soviet republics in Central Asia.

It is not hard to see that China is all over the place. Or is it?

The question is pertinent because the People's Republic has not been able or has been unwilling to forge a correspondence between its economic power and its political role on the global scene. Economically high-profile, it remains low-profile politically, earning the sobriquet of "Economic Giant, Political Dwarf".

Part of this is a matter of choice. Chinese leaders know that they govern a country that is still ridden by deep-rooted poverty and infrastructural backwardness. In terms of per capita income, China is still poorer than Iran, and even the Maldives islands. In terms of life-expectancy it is world number 102 among 198 nations.

Thus, Chinese leaders have preferred to remain essentially focused on domestic issues with priority to rapid economic growth. To them, getting involved in international politics seems a risky distraction.

However, the Chinese low profile has another reason: lack of experience in international affairs and the skilled manpower needed for punching above its weight in the diplomatic arena. It is interesting that not a single high-profile international post is filled by a Chinese diplomat, when diplomats from even Burma and Ghana have held the position of United Nations Secretary-General.

Rather than imitating the British or French styles of empire-building in the 19th century, China has opted for the Dutch model of going for trade and leaving politics to others. But is such a strategy sustainable? You might not want to go after politics, but what if politics comes after you?

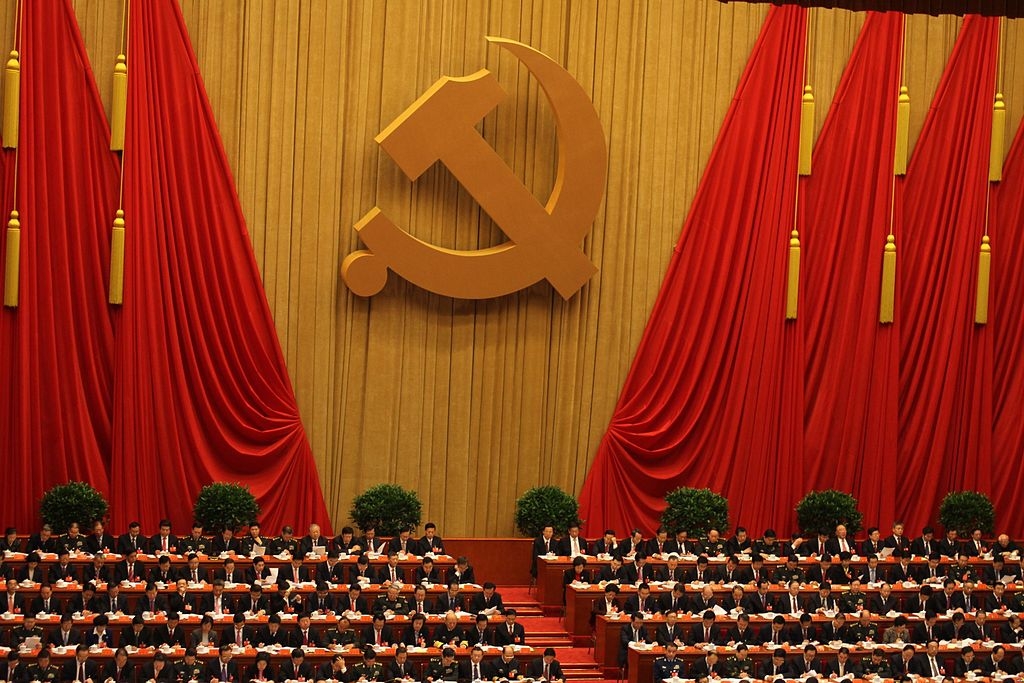

This is one of the questions likely to be raised at the five-day 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, due to open on Tuesday.

Though China has historically poor relations with neighbors, except Pakistan, it has a neutral profile elsewhere, notably in the Middle East, Africa, Europe and South America, if only because it does not bear the burden of a colonial and/or hegemonic past.

Because the Party's congresses are prepared in secret, it is hard to know whether or not a major review of the nation's foreign policy is included in deliberations. This week's congress will have two priorities.

The first is to consolidate Xi Jinping's position as "supreme leader", something more than mere Secretary-General.

This could be done by bestowing on him a lofty title as was the case with Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. President Xi, expected to be unanimously re-elected for a further five-year term, could also strengthen his position by propelling his protégés into key positions in the Central Committee, the Politburo, the Politburo Standing Committee, the Committee for Discipline and Inspection, and the Military Committee, the party's five key decision-making organs.

The second priority is a change of generations at the top the hierarchy with new figures born in the 1960s or later moving up the ladder. A majority of the 2,300 delegates slated to attend belong to the "new generation."

The new putative leadership consists of individuals with some experience of the outside world, often through studying in the United States and Western Europe. That could provide a greater understanding of world politics and a keener taste for getting involved.

One thing is certain: the international scene is in turmoil and Russia and the United States, still burdened by memories of the Cold War, might not always be able to provide the answers needed.

For its part the European Union, its economic power notwithstanding, cannot mobilize public opinion for a greater political role internationally. India, another rising power, is bogged down by its surreal quarrel with Pakistan, while hopes of Brazil emerging as a big player have faded; maybe for decades.

In other words, there is room for China to become a key player in global politics. Will she want that?

We shall know the answer in Beijing this week.

Pictured: The 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, in November 2012. (Image source: Voice of America/Wikimedia Commons) |

Amir Taheri, formerly editor of Iran's premier newspaper, Kayhan, before the Iranian revolution of 1979, is a prominent author based on Europe. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

This article first appeared in Asharq Al Awsat and is reprinted here with the kind permission of the author.