It was a hot July day in the central Anatolian city of Sivas, Turkey, in 1993. A group of Turkish intellectuals, mostly Alevis, including prominent writers, musicians, poets and artists, had gathered for a cultural festival at the downtown Hotel Madimak. The happy troupe came to commemorate the 16th century Alevi poet, Pir Sultan Abdal.

Among the intellectuals was one of Turkey's most famous writers and humorists, Aziz Nesin, who authored over 100 books that were translated into more than 30 languages. Not long before the assembly in Sivas, and sparking outrage from Islamist groups, Nesin had begun to translate Salman Rushdie's controversial book, "The Satanic Verses" into Turkish.

On July 2, shortly after Friday prayers, thousands of devout Sunni Muslims marched to the Hotel Madimak. They broke through the weak police barricades surrounding the hotel, chanting "Allah-u Aqbar (in Arabic, "God is the greatest.") When they reached the hotel, they set it alight, with policemen allegedly standing by and watching. The city's Islamist mayor refused to send fire brigades to put out the fire. The assault took eight hours, without any intervention from the police, military or fire department. When what would later be internationally known as the "Sivas massacre" ended and the mob dispersed, 35 people, mostly Alevi intellectuals as well as a Dutch anthropologist, had died, along with two hotel employees. Two arsonists also died. Ironically, Aziz Nesin survived the attack.

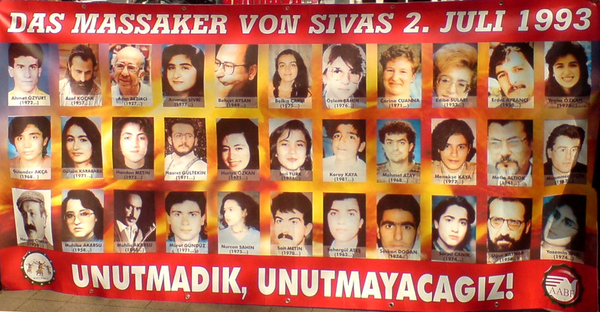

The faces of many of the victims who were murdered in the 1993 Sivas massacre are featured on this poster, used in a 2012 commemoration in Germany. (Image source: Bernd Schwabe, Wikimedia Commons) |

In the following days, a total of 190 people were arrested and charged with "attempting to establish a religious state by changing the constitutional order." After a trial, 33 suspects were sentenced to death, 99 received between 28 months and 15 years, and 37 were acquitted. As Turkey later (in 2002) abolished the death penalty, the death sentences were commuted. Each defendant received 35 life sentences, one for each murder victim, and additional time for other crimes.

These 33 convicts who ended up with life sentences -- except one who died in prison -- are currently the only ones still serving time for their crimes; the other defendants were paroled early or released after completing their sentences.

In March 2012, due to the statute of limitations, the Sivas massacre case against five remaining defendants was dropped.

On July 2, 2015, the Sivas massacre was commemorated on its 22nd anniversary. Families of the victims were joined at the commemoration ceremony by parliamentary deputies from the main opposition Republican People's Party. The group marched through Sivas and ended at the site of the Hotel Madimak where they laid carnations in memory of the victims. Unsurprisingly, Turkey's Islamist government was not represented at the commemoration.

In recent years, the government has been quite mean to the families of the victims: A request that the site of the Hotel Madimak be turned into a "museum of shame" was rejected. Instead, the Turkish government, in 2010, expropriated the property and turned it into a "museum of science."

There is hardly anything surprising about that. To this day, Islamist newspapers claim that the real victims are not those who were burned alive at the Hotel Madimak, but those who murdered them and have since remained in prison. One such newspaper ran the headline "Madimak is the name of oppression against Muslims." It said the families of the convicts were pleading to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan "for an end to the slavery of their relatives." They are probably pleading to the right person.

The right to defend a suspect (any suspect) is sacred in law, no matter what the alleged crime is. An army of lawyers rushed to offer their services to the Sivas massacre defendants, most probably on a pro bono basis. In reality, they probably felt this was part of the jihad -- this time taking place at courtrooms with jihadists in lawyers' robes. Those lawyers' career moves in later years are quite telling -- if not totally ironic.

One Sivas massacre defense attorney became the justice minister when the ruling Justice and Development Party's (AKP) earlier predecessor, Welfare Party (later banned by the Constitutional Court on charges of attempting to topple Turkey's secular regime) came to power in 1996. One was appointed as a member of the Constitutional Court by the AKP. One became an AKP state minister. Two became Erdogan's personal lawyers. Four became AKP members of parliament (MPs), with one AKP MP becoming a member of Parliament's constitutional commission. Three became AKP mayors. Two became AKP's provincial chairmen and two, deputy provincial chairmen. Two became directors at the AKP-controlled Istanbul municipality. And one was appointed by the AKP as a board member of the state-run news agency, Anatolia.

A big coincidence? Or just rewarding jihadists in lawyers' robes?

Burak Bekdil, based in Ankara, is a Turkish columnist for the Hürriyet Daily and a Fellow at the Middle East Forum.