The last few weeks have seen serious signs of interest in the Muslim world for the reform of Islam. They started with the heroic and honorable initiative at the end of 2014 by Egypt's President, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, criticizing the ideology of Islam. He comments on how it is hostile to the whole world, and calls for a "revolution" in Islam. This was followed up by an appeal by Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayyeb of Egypt's al-Azhar University, with calls for radical reform of religious teaching, although unheroically, dishonorably and not at all believably, still trying to pin the blame on others.

An Egyptian plan to combat radical Islamism is also on the agenda for the Arab summit in Sharm El Sheikh, on March 26th.

When Muslims themselves now understand there is an issue, politicians and key decision makers in Norway -- and all over Europe and the West, for that matter -- need to understand this, too, and back them up.

It is as if el-Sisi, al-Tayyeb and others have seen that Islam, as it now presents itself, might be regarded by many as a fear-based, power-seeking, expansionist political ideology, dressed up as a religion. It also could be viewed as having built-in control mechanisms, ensuring loyalty through threats, death threats or off-putting acts of violence for "apostasy;" "insulting the prophet;" not being "obedient enough;" not belonging to the "right" version of Islam; questioning or criticizing it in general; for just about any infraction, or for simply trying to exit. A leading Sunni Islamic theologian, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who is the spiritual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, has admitted that "if [Muslims] had gotten rid of the death sentence for apostasy, Islam would not exist today."

Here in Norway, critics of Islam's ideology are now starting to be heard, among them the journalist and editor Vedbjørn Selbekk, Hege Storhaug, pastor Einar Gelius and the fearless politician Per Sandberg.

Pastor Einar Gelius says that Islam needs to be questioned and criticized in its values and ideology, the same way as Christianity. Selbekk, a journalist and editor, created a furor back in 2006, when he dared to reprint some of the Mohammed cartoons published in the Danish newspaper, Jyllands-Posten. For this, he was predictably ostracized by then Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg. The current prime minister, Erna Solberg, however, recently expressed regret at the authorities' lack of support for him at the time.

Another issue that will have to be addressed is how Islam is presented in Europe's education system. The Norwegian translation of the Koran has been abridged to take out the less charming parts. So in mainstream Norwegian education, Islam is presented as if it were already reformed, and now is something no more threatening to anyone than, say, Quakers.

The crucial question here is: Will Islam now be reformed to meet the version found in the textbooks? Or will the textbooks be altered to describe accurately Islam's stated ideology? In schools, one does not usually teach expansionist political ideologies under the category of "religion." At the moment, the version on the market is just not telling Norway's indigenous population what is actually there.

Norway also has plans to deport at least 7,800 illegal asylum seekers this year, and has increased the budget for this by 150 million kroner (over $19 million). There were 7,529 deportations in 2014, with October setting a record at 834. In January 2015, 494 people were deported; of these 180 had a criminal record.

Representatives for Norway's police-run Deportation Department said last November that deportations have a positive effect on criminal statistics, as many asylum seekers are also criminal offenders.

Meanwhile, the press is still employing dirty tricks to discredit those who have knowledge of -- and reveal the more dismaying sides of -- Islam. There has been noticeably little media coverage of the interest in reform being expressed in the Middle East today. The focus here is still hell-bent on trying to mislead the population about the contents of Islam.

On a more positive note, for the first time in connection with International Women's Day (a big event in Norway), political attention was drawn to the problems of non-Western women, such as forced marriage and female genital mutilation.

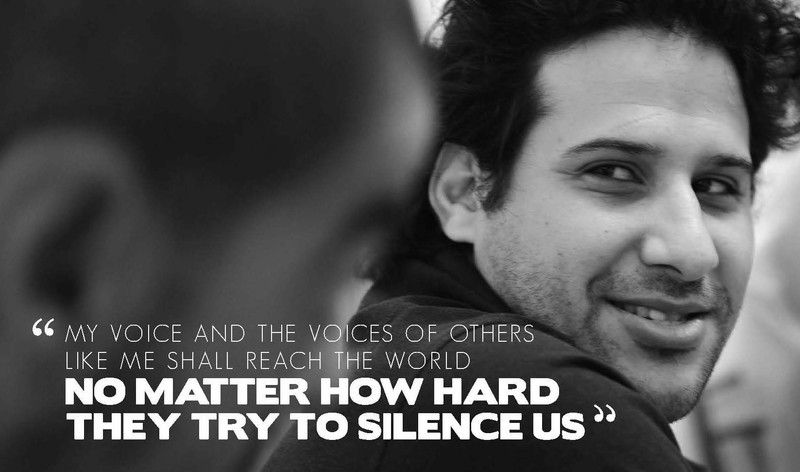

An important Norwegian voice in discussing issues related to culture, religion, women's issues, homosexuality and integration is Muslim Somalian-born Amal Aden, who has been living with death threats from Muslims for years. After been told by police only days earlier, for her own safety, to stop being so "loud" in debates, she has now had her police protection increased.

There is also a woeful tendency in Norway to "blame the victim," meaning that if you speak up, and there are negative consequences, they are your own fault -- if you had just kept your mouth shut, everything would have been fine. There does not seem to be much awareness that this self-censorship under threat was used in the former USSR and by other tyrants to stifle all dissent before it can even start. The result is that one ends up one censoring oneself into a death-spiral of submission to just about anything. This self-censorship, whether voluntary or the result of an implicit threat, is the death of enlightenment, humanism and the foundation of all science: the spirit of free inquiry.

A great irony exists in Norway between the enormous investment in school anti-bullying programs, accompanied by the openly vicious bullying and ridiculing of adults in the media.

It seems that every European country now has its police busy protecting those who wish to protect free speech. Those who bring the public's attention to potential problems with Islam, or who defend freedom of speech (the Netherlands' Geert Wilders, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Abdel Aboutaleb; Denmark's Lars Hedegaard, Sweden's Lars Wilks, Norway's Vebjørn Selbekk, Britain's Salman Rushdie -- and the list does not get shorter).

What does this all this say about the state of affairs in Europe, about democracy, freedom of speech and about Islam?

As the unpleasant sides of Islam play themselves out in what at times seems like an endless horror movie, people seem to be increasingly filled with discontent. They see that politicians are not listening to their concerns, and they wonder about alternative political solutions -- looking to candidates who seem as concerned as they are, or will offer more referendums, as Switzerland has done.

Constructively, politician Christian Tybring-Gjedde has pointed to what impedes Norway: conformity, consensus and the fact that media space is almost always given to pre-chosen purveyors of some the pre-chosen "truth." With this, Tybring-Gjedde indirectly points to Norway's destructive cultural tradition of Janteloven ("Jante Law"), which is named for a 1933 novel by Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose. The book addresses a social injunction that seems to run throughout Scandinavia: "Please do not get the idea that you are better than anyone else." The "Jante Law" is sometimes described as a condescending attitude towards individuality and success: denigrating the achievements of individuals, upholding groupthink, and belittling anyone who stands out, especially if he has accomplished something.

Clearly, this "Jante Law," as so many others, has outlived its presumed benefit.

Also in need of being tossed out is the fear of terms such as "racist" and "Islamophobe" -- and of criticism and disagreement in general. Politicians need to roll up their sleeves, get out of their comfort zones and take action. This matter is not going to go away on its own, no matter how much they might like it to.

The "Ring of Peace" initiative received international media attention and was a positive gesture. But surface-scratching, "rainbow generation" niceties and appeals for solidarity do not remove the key issues that need to be discussed -- Islam's contents; how these effects the way Muslims think and act, and what actions need to be taken to protect a decreasing, chewed-up democracy -- especially regarding freedom of speech -- and to protect the indigenous populations in Europe from an expansionist ideology, rather than increasingly pandering to Islam's demands, as seems currently to be the trend in most of Europe.

Progress can only come through a deeper knowledge of Islam; through actually deconstructing it. It is also high time to look at the positives that can come out of such a conflict.

Einar Berg's introduction to the Norwegian translation of the Koran (Universitetsforlaget, 1989) is revealing. It is almost apologetic in tone. It excuses the Koran of being a product of its times, and to be seen alone in that light. It is as if he were shocked by what he translated, and trying to package it in a more charming light. He recommends reading the Koran from back-to-front. The Koran's later parts are more violent and bloodthirsty than the earlier ones. Through "abrogation" (the practice whereby the texts from the latter part of Muhammad's life in Medina have been regarded by many Islamic scholars to supersede the earlier, softer ones, from when he started out in Mecca).

Berg's preference seems clear when compared to the acts of atrocity in the name of the Koran, Islam, jihad, Allah and allusions to various Islamic texts, all now taking place around the world. As such, Berg's introduction, by saying that the earlier (less violent) chapters are the more important ones, directly manipulates Islam and misleads the reader.

Needless to say, the contents that say "those fighting for Allah are worth more than the lives of those that stay at home" (Koran 4:95; the same message is repeated in other verses) spell out why many are joining ISIS. It also highlights how the ISIS interpretation of Islam belies the claim that Islam is simply a religion of peace or a guide to spiritual insight.

To be in denial of this fact is to betray one's own population. Chapter 4 is not alone in mentioning non-believers. Chapter 2, for example, has 286 verses, with 52 mentions of non-believers and what should happen to them -- a trait the runs throughout the whole Koran.

While Western politicians and others are now presumably aware of the texts that encourage the killing of non-believers, possibly more important is the pervasive, divisive focus on non-believers -- the insistence on disparaging them and killing them -- and how this might well condition the minds of many Muslims around the world, especially children.

As learning the Koran by heart as a child is seen as an important accomplishment in Islam, so the frequent mention of non-believers -- with such negative focus on others rather than on oneself -- can have a mind-conditioning effect on the reader.

The same conditioning is used to train soldiers before going to war, to condition their minds into believing the enemy is inferior and less than human, to make him easier to kill. The shocking difference is that Islam gives every child this conditioning. Imagine if those tenets were the desired ethical result of every Confirmation, every Bar Mitzvah or every First Holy Communion. In the worst-case scenario, the Koran's contents are "motivational training" for every single Muslim child to become a "Soldier of Allah." This hate-indoctrination can be seen in the countless videos at Memri or Palestinian Media Watch. Little Muslim children on Palestinian television preach anti-Jewish rhetoric, learned parrot-style from Islam's doctrines. The same conditioning can also be seen on videos showing the training of Muslim children in ISIS military camps.

Western politicians and countries need to come to grips with this. They would do well to stop preaching the lie of the "religion of peace," which, at this point, no one believes anymore anyway, and instead follow some of the legal changes just made in Austria.

Politicians who taking their jobs and responsibilities seriously need to take in the ways Islam differs from other religions.

If even el-Sisi and al-Tayyeb have seen that there is a need to act, it is time to take sides with them and with those who say there is a problem, and at least discuss reform. Taking uncomfortable facts on board often leaves one with a sense of discomfort and unease perhaps, but is important for the health of all societies in the long run. Violence and dualism need to be addressed, and courageous Muslim visionaries, such as el-Sisi and the many others speaking out, need our serious support.

Bjorn Jansen is based in Norway.