Once again, Israel and Hamas have agreed upon a so-called "cease fire." Once again, as Hamas regards all of Israel as "Occupied Palestine," the agreement will inevitably fail. And once again, for Israel and the wider "international community," there will be significantly dark consequences for international justice.

In specifically jurisprudential terms, the immediate effect of this latest cease-fire will be wrongfully to bestow upon the leading Palestinian terror organization (1) a generally enhanced position under international law; and (2) a status of formal legal equivalence with Israel, its beleaguered terror target.

The longer-term effect will be seriously to undermine the legitimacy and effectiveness of international law itself.

No authoritative system of law can allow or encourage accommodation between a proper national government and an unambiguously criminal organization. In this connection, however unintentionally, Israel should not further support its relentless terrorist adversary in Gaza by agreeing to any temporary cessation of hostilities. Instead, it should continue to do whatever is needed in tactical or operational terms, while reminding the world that the core conflict here is between an imperiled sovereign state (one that meets all codified criteria of legitimacy of the Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, 1934) and an insurgent organization that (a) meets none of these criteria, and (b) systematically violates all binding expectations of international humanitarian law.

By definition, under pertinent rules, Hamas is an illegal organization. This inherent illegality is readily deducible from the far-reaching criminalization of terrorism under authoritative international law; hence, it can never be correctly challenged by well-intentioned third parties (e.g., the United States), even in the presumably overriding interests of peace.

There have always been straightforward and readily determinable rules of warfare, some dating to codes even more ancient than the Hebrew Bible. Untraditionally, these "peremptory" rules bind all insurgent forces, not only uniformed national armies. Their overriding point is that "the only legitimate object which states should endeavor to accomplish during war is to weaken the military forces of the enemy." It is a core or "peremptory" principle that was carried forward with certain nuances in 1977, in Geneva Protocol 1, Article 48.

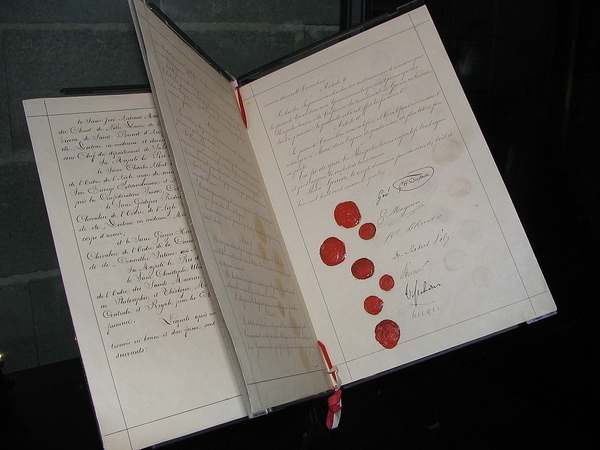

Most conspicuously, these rules derive from the St. Petersburg Declaration (1868), which followed upon still earlier limitations identified at the First Geneva Convention of 1864.

Original document of the first Geneva Convention, 1864. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) |

In any conflict, under law, the means that can be used to injure an enemy are not unlimited. No matter how hard those who would justify the willful maiming and execution of noncombatants in the name of some abstract ideal may try to institute certain self-serving manipulations of language, these people misrepresent international law. Always.

Whenever Palestinian insurgents (Hamas, Fatah, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Islamic Jihad; it makes no legal difference) claim a right to use "any means necessary," they are trying to deceive. Even if their corollary claims for "national self-determination" were in some way sensible and supportable, there would still remain certain authoritative limits on permissible targets and weapons. Even if an insurgent group claims the legal right to wage violent conflict for "self-determination" -- Hamas's argument -- the group does not have a corresponding right to use force against the innocent. In short, under humanitarian international law, the ends can never justify the means. Never.

Intentional forms of violence deliberately directed against the innocent are always far more than "merely" repugnant. They are also always unlawful.

While it is true that certain insurgencies can be appropriately judged lawful, any such permissible resorts to force must nonetheless conform to the unequivocal laws of war.

Even if incessant Palestinian cries of "occupation" were somehow reasonable rather than contrived, any corresponding claims of entitlement to oppose Israel "by any means necessary" would remain totally unfounded. Palestinian cries of "occupation" are contrived not only because Israel had already physically left Gaza completely in 2005 -- maintaining a partial blockade only for its own self-defense, as now can be seen was justified -- but also because the alleged right of Palestinian self-determination is factually overridden by a long history of Jewish claims to that land. These claims include the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the subsequent San Remo Treaty of 1920, and the British Mandate for Palestine.

International law has very precise form and content. It cannot be invented and reinvented by terror groups or aspiring states ("Palestine"), merely to accommodate their own presumed geo-strategic interests. On November 29, 2012, the Palestinian Authority [PA] was upgraded by the U.N. General Assembly to the status of a "nonmember observer state," but significantly, the PA has since declared itself nonexistent. On January 3, 2013, Mahmoud Abbas formally "decreed" the absorption of the "former PA into the State of Palestine." While this administrative action did effectively and jurisprudentially eliminate the PA, it assuredly did not succeed in creating a new state by simple fiat. The pertinent expectations under international law -- codified by, among others, the Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (Montevideo Convention) of 1934 -- were not met.

Leaving aside Abbas's illegal refusal to follow the Palestinians' binding obligation to negotiate full sovereignty directly with Israel, the evident criteria of "nonmember observer state" also fell far short of expectations of the only authoritative international treaty on statehood. This governing document is the Convention on the Rights and Duties of States of 1934.

National liberation movements that fail to meet the test of "Just Means" are never legitimate. "Just Means" refers one of the two criteria that must be applied to any insurgent movement. It refers to the weapons and targets involved, again as in the St. Petersburg Declaration. The other criterion, "Just Cause," has to do with the consideration of just and unjust wars: Does a cause warrant a proper resort to force?

Even if we were to accept the argument that Palestinian insurgent groups somehow met the criteria of "just cause," they would not meet the additionally limiting standards of discrimination, proportionality, and military necessity. These compulsory standards have been applied to insurgent organizations by the common Article 3 of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, and also by the two authoritative protocols to these Conventions of 1977.

These compulsory standards are also binding upon all combatants by virtue of broader customary and conventional international law, including Article 1 of the Preamble to the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907. This rule, called the "Martens Clause," makes all persons responsible for upholding the "laws of humanity," and for the "dictates of public conscience."

Every use of force by Palestinian insurgents must be judged twice: once with regard to the justness of the objective, and once with regard to the justness of the violent means employed.

American and European supporters of a Palestinian state continue to believe that this 23rd Arab country will somehow be part of a "two-state solution," despite its continuing protestations to the contrary. This odd presumption is also contradicted almost everywhere in the Arab and Islamic world.

Terrorist crimes of the sort committed daily by Hamas mandate universal cooperation in apprehension and punishment. As punishers of "grave breaches" under international law, all states are expected to search out and prosecute, or extradite, individual terrorist perpetrators. In no circumstances, under international law, are states permitted to characterize terrorists as "freedom fighters."

In the final analysis, the United Nations and the broader international community should now be working in tandem with Israel to delegitimize and disarm Hamas, not to broker an intrinsically illegal cease-fire with a criminal organization.

The best option for the international community would be to adhere to the principle that Hamas is an inherently illegal (terrorist) organization. There is a civilizational obligation -- as with Boko Haram, al-Qaeda and the IS -- to oppose this form of international criminality.

Professor Louis René Beres, born in Zürich, Switzerland, is the author of many books and articles on terrorism, counterterrorism and international law. He holds a Ph.D. in International Law from Princeton.