On the occasion of a preparatory meeting for the 25th summit of the Arab League in Kuwait, the Libyan government, on March 25, opened the debate on the restoration of the monarchy in the country. "The restoration of the monarchy [in Libya] is the solution that will guarantee the return to security and stability. Contacts have already been made, and we are in touch with dignitaries and tribal chiefs in Libya, and also with the grandson of King Al-Senussi, Prince Mohamed [Hasan Al-Rida Al-Senussi], who lives overseas," said the Libyan Foreign Minister, Mohamed Abdelaziz, during the meeting. He added that "many tribal sheikhs, who lived under monarchy and know it, prefer such a system of government."[1]

In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the fragmentation of the Libyan society has been particularly severe, and chances of the country's dissolution are high. Libyan Foreign Minister Abdelziz believes that the return of the Senussi rule -- the Senussi dynasty has always been considered a symbol of national unity -- may stabilize the country. Sidi Muhammad Idris Al-Senussi, the last king of Libya, ruled from 1951 to 1969, the year he was toppled by a military coup led by Libya's former dictator, Muammar Gaddafi[2].

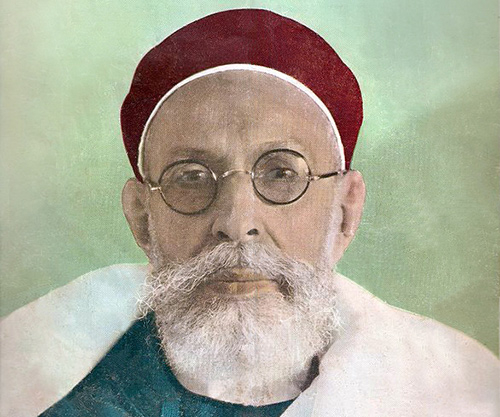

King Idris I of Libya on the cover of Al Iza'a magazine, August 15, 1965, No.14. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) |

After the toppling of King Idris in 1969, Gaddafi imposed on the country 42 years of harsh and unstable dictatorship that did not build any much-needed national unity. The fall of Gaddafi did not bring any social peace. Tensions within the country are growing. Tribal confrontations, common delinquency and Islamist extremism are tearing the country apart. Dr. Mohamed Chtatou, Professor at the University of Mohammed V in Rabat, Morocco, wrote that if Libya does not find a national cohesion, it risks becoming a failed state like Somalia:

In Libya, there is a government that has, on paper, a police and an army, but this government exists only in Tripoli [the capital]; outside of the capital, the country is ruled by the militias. Actually, the Libyan example is very close to the Somali experience. If the government fails in the months to come to assert its power on all the Libyan territory, the country will become a de facto Somalia II, in the area. In principle, Libya is already another Somalia: the militias, in certain parts of the country, are already selling oil to foreign companies and pocketing the money. Soon, these militias, if they have not already done so, will have their own government that will contest the decisions of the paper government of Tripoli. Post-Qaddafi Libya is bent on becoming three countries or more if nothing is done on the part of the Tripoli paper government. Indicators show that it is slowly fragmenting into three countries: Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan. The only bold initiative that could ultimately reverse this motion is the creation of a federal government that would delegate home affairs to local governments. Will the Libyan political class opt for that or go the way of the irreversible fragmentation?"[3]

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that the Libyan leadership imagined that the only way out of the present chaos was represented by the reinstatement of the Senussi dynasty, the only institution that, in the course of the young history of Libya, had ensured some sort of national sentiment and of security and stability.

In the meantime, the Libyan government recently issued a decree stipulating that the heirs of King Idris will regain their Libyan citizenship and can recover the property confiscated by former dictator Gaddafi. After the coup in 1969, the Senussi family was actually stripped of Libyan citizenship and thrown out of the country. King Idris died in exile in Egypt. The rest of the family, including Idris's grandnephew and heir-apparent, Mohamed Al-Senussi, received the status of political exile the United Kingdom.

The process of restoration of the monarchy, however, does not convince the Senussi family itself. In a recent interview to the BBC, Mohammed Al-Senussi, the heir-apparent, said that monarchy cannot work in post-revolutionary Libya, and added that he does not have any desire to rule the country.

According to Asharq Al-Awsat columnist Mishari Al-Zaydi, Prince Senussi is right to refrain from responding to such call, "not because the Senussi monarchy is not the solution, but because there are no guarantees of its success, and times have changed. ... there is no evidence that this nostalgia for the monarchy stems from deep-seated conviction."[4]

"Similar calls [for the restoration of a monarchy] were made in Iraq following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, and they appear every now and then in Egypt," according to Al-Zaydi.

In Libya, it seems unlikely that a monarchy might be a sort of magic wand capable of producing instant results on the social texture of Libya. It appears as though, after the many hopes raised by the Arab Spring, Libya, as many other Arab countries, is back at square one.

The Libyan government does not know how to come out of instability or stop the violence, and citizens are losing hope and respect for the institutions governing the country.

A Martyr Ministry employee, Ali Al-Houti, interviewed by the media outlet Magharebia, commented, "As far as I'm concerned, I accept even Libyan folklore artist Nadia Astar to rule Libya, as long as we get rid of these assassinations, bombings and concerns in the country."[5]

[1] Magharebia.com, March 28, 2014

[2] King Idris inherited from his father the title of emir of Cyrenaica, the eastern coastal region where he was born. Idris' grandfather was Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali Al-Senussi, also called the Grand Senussi, who founded in Mecca (Saudi Arabia) a political and religious Sufi order bearing the name of his family. Grand Senussi promoted his politico-religious movement across Libya, Egypt and other parts of North Africa. The Senussi movement fought French colonial expansion in the Sahara and the Italian colonization of Libya. Idris himself confronted the Italian colonial rule and supported the Allies against Nazi Germany, during WWII. After the war, the UN General Assembly announced that the future of the Libyan provinces - Cyrenaica, Fezzan, and Tripolitania - should be decided upon by representatives of the three areas in a national assembly. This assembly established a constitutional monarchy and a consensus was reached to offer the throne to Idris. The new king declared Libya's independence in December 1951.

[3] Morocco World News (Morocco), April 2, 2014

[4]Asharq Al-Awsat (Saudi-owned, London-based), March 30, 2014

[5] Magharebia.com, March 28, 2014