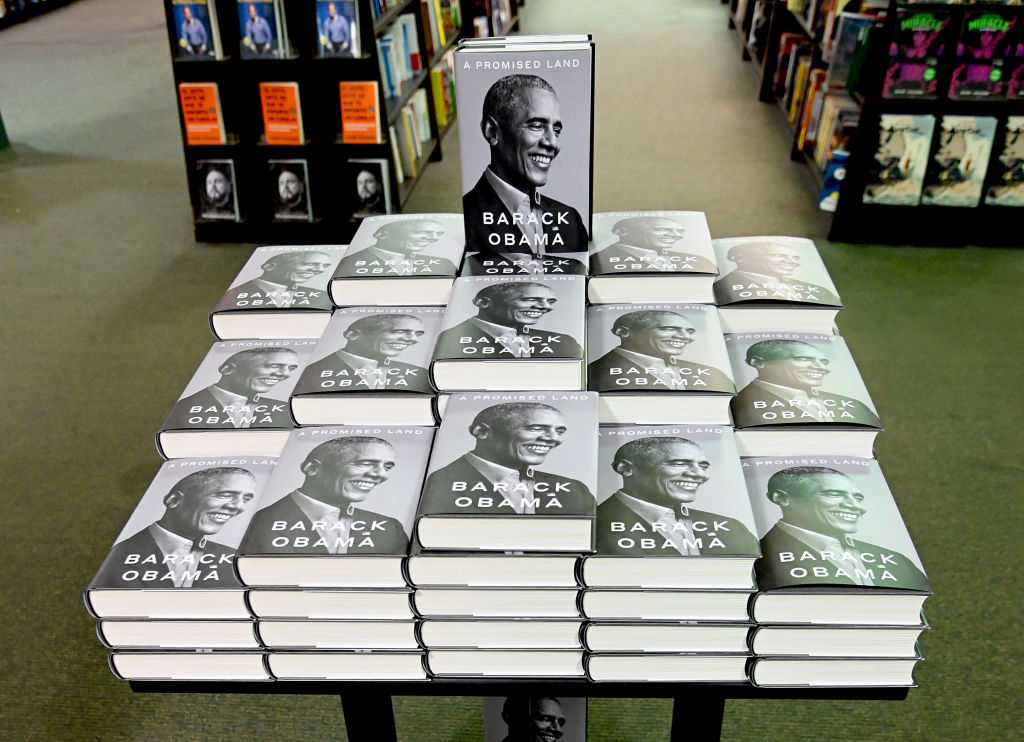

(Photo by Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images) |

All through his brief political career, Barack Obama, the 44th President of the United States, has mused about what he sees as his "otherness". In his latest book, A Promised Land, he claims that people saw him as someone "from everywhere and nowhere, a combination of ill-fitting parts like a platypus or some imaginary beast."

However, even if that were true, Obama's "otherness" could be found elsewhere. To start with, he was the first person to win the US presidency after a brief stint in public office as a junior senator. (His successor Donald Trump didn't have even that). Obama was also the first person to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize without having done anything for peace or war.

With A Promised Land, he reveals another aspect of his "otherness." He becomes the first US president to write not one but three autobiographies. Even then, his new book, 768 pages long in the American edition, is presented as only the first volume, with a second yet to be written. Taken together, Obama's three autobiographies break the record set by President Ulysses S Grant with his 1,100 pages long memoirs.

A good chunk of the present book is a rehash of Obama's two previous offerings Dreams from My Father and The Audacity of Hope that covered his childhood and youth. Here, too, he maintains an air of mystery about his formative years in Indonesia. He is equally parsimonious in describing the influences that shaped his worldview. He says he read anything and everything, from Marx and Marcuse to Foucault and Virginia Woolf, but does not say what he learned from them.

Obsessed with his "otherness", Obama relates how he had to decide whether to develop himself as a black figure or a white one, finally deciding on the former. Having prioritized his "blackness," he then decided to act as a white man, thus "understanding" why some "whites" had "an emotional, almost visceral reaction to my presidency."

He also writes that his "very presence in the White House triggered a deep-seated panic." Although he offers no evidence, the pirouette enables him to claim victimhood, something fashionable in recent US history. That in turn, helps him dismiss criticism of his presidency as racism.

Yet, he writes: "My conviction that racism was not inevitable may explain my willingness to defend the American ideal."

Even then, it is hard to know where Obama stands on anything.

In discussing issues, he uses what one might call "on the one hand-on the other hand" stratagem. In some fields, for example foreign policy, he terms that "leading from behind." But, then he ends up a control freak. He relates one incident when, on official visit to Brazil, aides informed him that US air command sought his orders to bomb targets in Libya although he had announced that European allies, Britain and France, were in the lead there.

In Iraq, US field commanders could not use Apache helicopter gunships against terrorist forces without Obama's clearance.

Obama mocks suggestions by some critics that he may be a closet socialist, as if being socialist were dishonorable. But then, on possibly unguarded moments, he reveals his penchant for collectivism.

He praises "the collectivist spirit, a thing we all wish for - a sense of connection that overrides our differences." Repeating the claim of collectivists from Plato to Mao Zedong, he claims that the "regulatory state has made American lives a hell of a lot better." It was in that spirit that Obama tried to set up a state-controlled health sector, accounting for some 14% of the US GDP, with what he calls "Obamacare." He speaks of "community rights" while in the Bill of Rights, rights are granted to individual citizens.

Obama's "collectivist spirit" goes even further. He calls on American youths to "match the reality of America with its ideals." In even more hyperbolic tones, he talks of "remaking the world, to bring about an America that finally aligns with all that is best in us."

Such phrases put him in the category of socio-political engineers who think they could remake the world by exercising power. They do not realize that Frankenstein and Pygmalion are, in fact, the same story indicating the risks of such engineering.

Obama doesn't say why he didn't manage to do any of that during his presidency.

The good news is that Obama never decided who he really was and what he really wanted, besides being liked by as many as possible. Writing about the initial phases of his quest for the presidency, he wonders that he may have been motivated by "raw hunger, blind ambition wrapped in the gauzy language of service."

On being told that he had received the Nobel Peace Prize, he asks "For what?" But he doesn't put that question to those who gave him the prize. Instead, he plays the game by making a speech. Making speeches, of course, was what he liked best. His speech covered everything from saving the planet to the need for transgender washrooms.

Describing himself as "a conservative in temperament but not in vision" he implicitly admits that he lacked the courage of his assumed convictions.

Donald Trump makes a cameo appearance in the story as an orange ghost that gave Obama some unhappy moments with a campaign to prove Obama wasn't born in the US. Obama claims Trump was motivated by chagrin, as his two attempts at getting building contracts from the government had been dismissed by the White House. Obama writes: "For millions of Americans spooked by a black man in the White House, he [Trump] promised an elixir for their racial anxiety."

The book has tidbits about other leaders and political figures, all designed to cut them down to size and lengthen the shadow of Obama's grandeur. Obama says he admires the Queen of England and found India's Sonia Gandhi attractive. But David Cameron, the British Prime Minister, was a rich boy who never experienced poverty. French President Nicolas Sarkozy was a "bantam cock". Russian President Vladimir Putin, "physically unremarkable", reminded Obama of Al Capone. Russian stop-gap President Dmitry Medvedev was a bad liar. Chinese President Hu Jintao was a boring bureaucrat with endless notes.

Obama describes Joe Biden, his Vice President, as "decent, honest and loyal" but not a luminary, let alone a potential leader. He also reveals that Biden opposed the killing of terror chief Osama Bin Laden.

A Promised Land doesn't make it clear to whom was America promised and ends with the killing of Bin Laden. An account of what Obama didn't or couldn't do remains for the next volume. The Guantanamo Bay camp remains open, although Obama promised to close it in first year of his tenure. The promise to create a Palestinian state in the same first year remains unfulfilled. The so-called "Arab Spring" became a disaster. The "Grand Bargain" with the mullahs of Tehran fizzled into a tragi-comic number. The "red line" set in Syria became pink and then disappeared altogether. The oceans that were supposed to recede, haven't. Putin, who was supposed to be contained, is still land-grabbing, while China, now under Xi Jinping, is claiming world leadership. US military involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan continues, and Obama has entered history as the president who killed more people by drone attacks in more countries than any other president. At home, the have-a-lot had even more under Obama while the have-little ended up with less. Even racist attacks and gun violence reached peaks never seen before while Obama made speeches, traveled around the world and mused about his "otherness."

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987.

This article was originally published by Asharq al-Awsat and is reprinted by kind permission of the author.