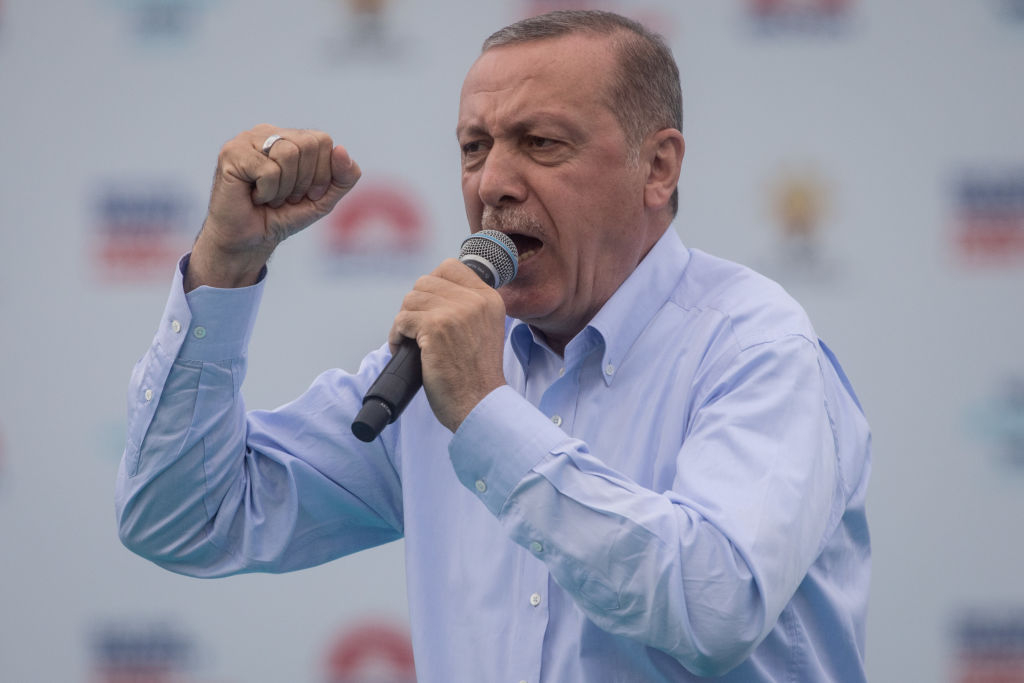

Fearing a sharp decline in his approval rating, especially in view of a looming economic crisis, Turkey's Islamist strongman, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, appears to be chasing new wars with real or imaginary enemies. (Photo by Chris McGrath/Getty Images) |

Fearing a sharp decline in his approval rating, especially in view of a looming economic crisis, Turkey's Islamist strongman, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, appears to be chasing new wars with real or imaginary enemies.

Election data and research show that Turks have a tendency to unite behind their leader in times of crises or confrontation with foreign enemies. According to the Turkish pollster Metropoll, for example, Erdoğan's approval rating peaked to 71.1% in December 2013, when he portrayed a slew of corruption allegations about him and his family as "a coup attempt." In parliamentary elections in 2015, Erdoğan's nationwide vote fell to 37.5% and his Justice and Development Party lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since it came to power in 2002.

Erdoğan's approval rating rose sharply again to 67.6% after a failed putsch against his government in July 2016. At the height of the COVID-19 crisis his rating was a strong 55.8%. Metropoll said Erdoğan's current approval rating is at 50.6%. He thinks he needs new tensions with Turkey's past and present-day adversaries.

Most recently, condemning the historic normalization deal between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Erdoğan said that "because we stand by Palestine," he is considering withdrawing Turkey's ambassador from the UAE. "I gave instructions to my foreign minister... We may suspend diplomatic relations [with the UAE] or recall our ambassador to Abu Dhabi," Erdoğan added.

If he does so, Turkey will be the only country in the region that has no diplomatic relations with Armenia and Cyprus, and no ambassadorial-level relations with Syria, Israel, Egypt and the UAE. Turkey's relations with many countries where it has full diplomatic ties are not in much better shape.

In late July, even before the UAE-Israel deal, Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar told Al Jazeera that Turkey would hold Abu Dhabi, the leading emirate, accountable at the right time and place for "malicious actions committed in Libya and Syria." He said that the UAE is "a functional country that serves others politically or militarily and is used remotely."

Turkey evidently has deep ire for any deal that may help stabilize one of the world's most volatile regions. On August 3, the Turkish Foreign Ministry condemned an oil agreement concluded between a US-based company and Syrian Kurds for the development of oil fields in northeastern Syria. In northwestern Syria, where Turkey controls small pockets of land, Ankara threatened to respond militarily to potential attacks on its forces.

There are "hotter" disputes, as well. Ignoring international efforts to find a diplomatic solution to maritime border disputes with its traditional Aegean rival, Greece, on August 10, Turkey resumed oil and gas exploration in the Mediterranean Sea -- only days after Turkey's government said it would delay offshore surveys to seek a diplomatic resolution with Greece.

French President Emmanuel Macron called for Turkey to be sanctioned and accused its government of violating the rights of Greece and Cyprus. In the face of increasing Turkish assertiveness, Macron also ordered the French Navy to the Eastern Mediterranean to provide military assistance to Greece. In a further move, France signed a defense deal with Cyprus. The agreement came into effect on August 1. The two-year Defense Cooperation Agreement covers energy, crisis management, counter-terrorism and maritime security cooperation between Cyprus and France.

While the standoff was deepening, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis convened his national security council. A statement issued after the meetings was reminiscent of pre-war times: "We are in complete political and operational readiness," Minister of State George Gerapetritis said on state television channel ERT. "Most of the fleet is ready to be deployed wherever necessary."

If you add to that perilous picture the Cypriot, Israeli and Egyptian navies, Turkey is up against formidable naval forces in the Mediterranean. In one dangerous incident on August 14, two warships, the Greek Navy's Limnos frigate and Turkey's TCG Kemalreis, collided in the Eastern Mediterranean.

All those Turkish-Greek tensions in the Aegean and Mediterranean seas bolster a century-long Turkish nostalgia to take back some of the Greek islands. Yeni Safak, a fiercely pro-Erdoğan newspaper, suggested that the Turkish military should invade 16 Greek islands.

The website Greek City Times commented:

"Discussion of wars and invading Greek islands is... a tactic used by the regime of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to distract the Turkish population from the woeful economic situation,"

Erdoğan's idea of vote-hunting by regional troublemaking is not limited to naval adventures only. Against the background of a sudden border flare-up between Azerbaijan and Armenia on July 12, the Turkish and Azeri militaries launched a two-week long joint military exercise, involving the traditional allies' air and ground forces.

In Turkey's southeast, Iraq blamed Ankara for a drone attack that killed two high-ranking Iraqi military officers. The incident occurred shortly before a planned visit by Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar to Baghdad. A fuming Iraqi government said the Turkish minister was no longer welcome.

Erdoğan needs epic stories of military might against real or fabricated foreign enemies to tell an increasing number of grudging voters in the face of an ailing economy. That is bad news for the entire region.

Burak Bekdil, one of Turkey's leading journalists, was recently fired from the country's most noted newspaper after 29 years, for writing in Gatestone what is taking place in Turkey. He is a Fellow at the Middle East Forum.