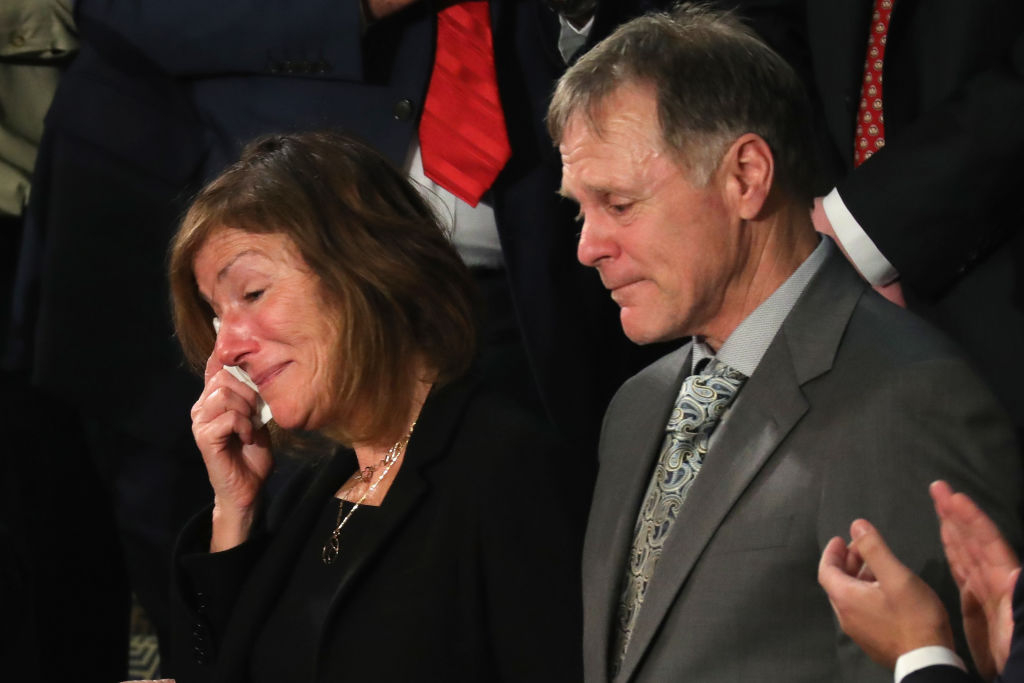

U.S. President Donald Trump believes he faces a dilemma: that his efforts on behalf of the parents of Otto Warmbier -- the University of Virginia student whom North Korean authorities detained, brutalized and killed -- undermine his ability to take away nuclear weapons from Kim Jong Un. Pictured: Fred and Cindy Warmbier, Otto's parents, are acknowledged during President Trump's State of the Union address on January 30, 2018. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images) |

"I'm in such a horrible position, because in one way I have to negotiate," U.S. President Donald Trump said at CPAC on March 2, while talking about efforts to disarm North Korea. "In the other way, I love Mr. and Mrs. Warmbier, and I love Otto."

Trump believes he faces a dilemma: that his efforts on behalf of the parents of Otto Warmbier -- the University of Virginia student whom North Korean authorities detained, brutalized and killed -- undermine his ability to take away nuclear weapons from Kim Jong Un, the leader of that horrific regime.

The president at CPAC summed up his perceived predicament this way: "It's a very, very delicate balance."

But is there really a "delicate balance"? Trump and predecessors have thought they should not vigorously raise human rights concerns while negotiating on various matters with the ruling Kim dynasty of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK).

American leaders have been wrong. The best way to get what we want from North Korea, whether it be "denuclearization" or anything else, is to reverse decades of Washington thinking and raise the issue of human rights loudly and incessantly. The same is true with regard to North Korea's sponsor and only formal ally, the People's Republic of China.

The U.S. has deterred a general attack on South Korea since the armistice of July 1953, but apart from this achievement, American policy toward North Korea has been an abysmal failure. A destitute state has held the most powerful nation in history at bay, while getting away with, among other things, building weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and proliferating WMD technology and ballistic missiles.

Given the imbalance in power, something is clearly wrong with Washington's policy. As Greg Scarlatoiu executive director of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, told Gatestone, "For almost thirty years, human rights was sacrificed on the altar of very serious political, security, and military concerns, and yet no significant progress has been made on nukes or missiles."

Therefore it is, as Scarlatoiu suggests, time for "a different approach."

Many, including President Trump, argue for the old approach, that he must build friendly relations. Trump has, as have all his predecessors starting with George H. W. Bush, tried to reason with the Kim family and entice it into cooperation.

Unfortunately, there is more than three decades of history to show that the Kims are impervious to enticement. Beijing, we should remember, has been in the enticement business for decades, and so has Seoul, especially during the successive presidencies of two "progressives," Kim Dae Jung and Roh Moo-hyun, who governed from 1998 to 2008.

The Kims, through three generations, have run a militant state and do not respond in the same ways as leaders of democratic societies. Because democracies are inherently legitimate, their presidents and prime ministers often fail to realize the vulnerability resulting from the illegitimacy -- and insecurity -- of despots such as the Kims.

In the illegitimacy and insecurity of the Kims there is power for others. Suzanne Scholte, chair of the North Korea Freedom Coalition, told Gatestone that when North Korea's most senior defector, Hwang Jang Yop, left the North in 1997, he warned, in Scholte's words, that "human rights was the regime's Achilles heel and most important issue." In an email message this month, Scholte wrote:

"Perhaps the worst aspect of not addressing the human rights concerns in North Korea is that it feeds into the lies of the Kim regime to justify its nuclear weapons program. The regime justifies diverting resources from its citizens to develop nuclear weapons with the lie that the United States is their enemy and wants to destroy them."

When we do not talk about our vision for a better future for North Korea's people, we inadvertently bolster Kim family propaganda.

The way to get what we want from North Korea is to expose that lie and thereby separate Kim Jong Un from regime officials and supporters. "If you are an elite member of North Korea society, you wake up every morning with a simple choice: slavish devotion to Kim Jong Un or seeing your family murdered in front of you before your own brutal execution," Scholte noted. Therefore, holding out the prospect of human rights and prosperity for North Koreans gives them "another option," in other words, "a peaceful way to bring change in North Korea."

Furthermore, there is one more reason to raise human rights to disarm the Kim regime. Kim Jong Un knows how inhumane his rule is -- he has, after all, had hundreds of people executed -- so if we do not talk forcefully about, say, Otto Warmbier, Kim will think we are afraid of him. If he thinks we are afraid of him, he will see no reason to be accommodating. It is unfortunate, but outsiders cannot be polite or friendly: Kim logic is the opposite of logic in free societies.

There is actually a real-world example of what happens when U.S. policymakers signal to aggressive leaders that they are afraid of talking about human rights. In February 2009, then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton famously proclaimed that human rights issues could not take precedence over other matters. Human rights, she said, "can't interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate change crisis, and the security crisis."

The rhetorical concession, meant to pave the way for cooperation, in fact had the opposite effect. China's leaders were "ecstatic" about Clinton's downgrading of human rights. "In their eyes, America had finally succumbed to a full kowtow before the celestial emperor," wrote Laurence Brahm, an American with close ties to Chinese leaders at the time.

Within a few weeks of Mrs. Clinton's ill-conceived pronouncement, the Chinese felt bold enough to harass two unarmed U.S. Navy reconnaissance vessels in international waters, in both the South China and Yellow Seas. In one of those incidents, Chinese boats tried to saw off a towed array sonar from the Impeccable, an act constituting a direct attack on the United States. Moreover, China's leaders did not prove to be helpful on the matters Clinton had listed.

It is time to let Kim Jong Un know that America no longer cares about how he feels or even about maintaining a friendly relationship with him. That posture, a radical departure from Washington thinking, is both more consistent with American ideals and a step toward a policy that Kim will respect.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of Nuclear Showdown: North Korea Takes On the World and a Gatestone Institute Distinguished Senior Fellow.